The Evangelism and Missions Archives holds over seven hundred processed collections. Some correspondence in our purchased microfilm stretches back into the 1600s, but we also have documents and media from as recent as the current year. The predominant time frame for most of the evangelistic and missionary activity documented in these collections, however, is the 20th century. As the Archives’ name suggests, the topics that hold together all the collections are evangelism and missions.

But to assume that the Archives only reflects these two areas is to miss the depth and breadth that these primary sources offer. Many collections also document social movements, political events, cultural trends, and more in the countries where missionaries and evangelists happened to find themselves. It is still surprising to discover unexpected points of convergence between collections that we archivists never anticipated or noticed until a collection was arranged and described to be fully open to the public. Four examples come to mind:

- Presbyterian missionaries Howard Thomas and Ruth Thomas reported in their oral histories on their first-hand experience and observation of the opium trade in Southeast Asia. Working in the area known as the Golden Triangle that sprawls across Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, and Southwest China, where the majority of the world’s opium until recently was produced, the Thomas’ accounts testify to the trades’ effect on the economies, development, and spiritual lives of its citizens.

- Africa Inland Mission missionaries reported (see Collection 81, Folders 33-25 and 26, 36-9,10,11, and 12) on the impact of rebellion in the Belgian Congo on their communities, churches, and ability to carry out their work. This example of Africa’s independence movements showed the growing exercise of indigenous power to establish governments and economies in the hands of their citizens as European colonial powers were displaced.

- Victor Plymire, an Assemblies of God missionary in Tibet in the 1930s, was also a skilled photographer who documented the everyday life, cultural practices, and landscape of this remote nation in his black and white photographs.

- The publication Christianity Today and one of its founders, L. Nelson Bell (who was also Billy Graham’s father-in-law), not only reported on religious activity and theological views of evangelicals, but also wrote on American social issues, especially from the 1970s onward when evangelicals became more engaged in conservative politics.

Another recently uncovered example of these unexpected intersections is the collaboration of two evangelists: Leighton Ford and Tom Skinner. Ford was an associate evangelist with the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. Skinner was a Black Christian leader who emerged in the 1960s and ‘70s as an evangelist and social activist who sought to challenge America’s evangelicals and young people to address the need for racial justice, the ongoing impact of social and economic disparities for the Black community, and the gospel’s implications for economics, law, and politics. These were turbulent days when broad cultural shifts were underway in the country and America’s Christian population. The Civil Rights Movement was laboring to establish equity between the races, university students were protesting America’s involvement in the Vietnam War, and the Jesus People were finding a new voice for their new-found faith in Christ.

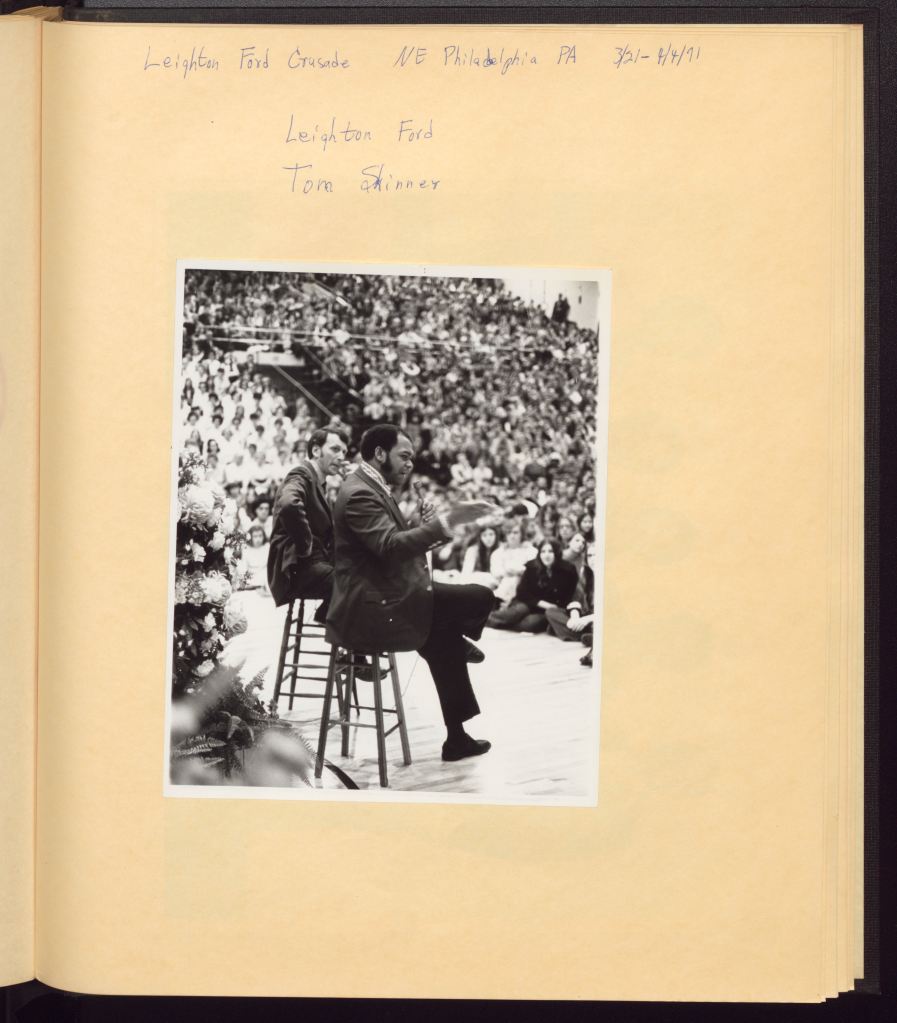

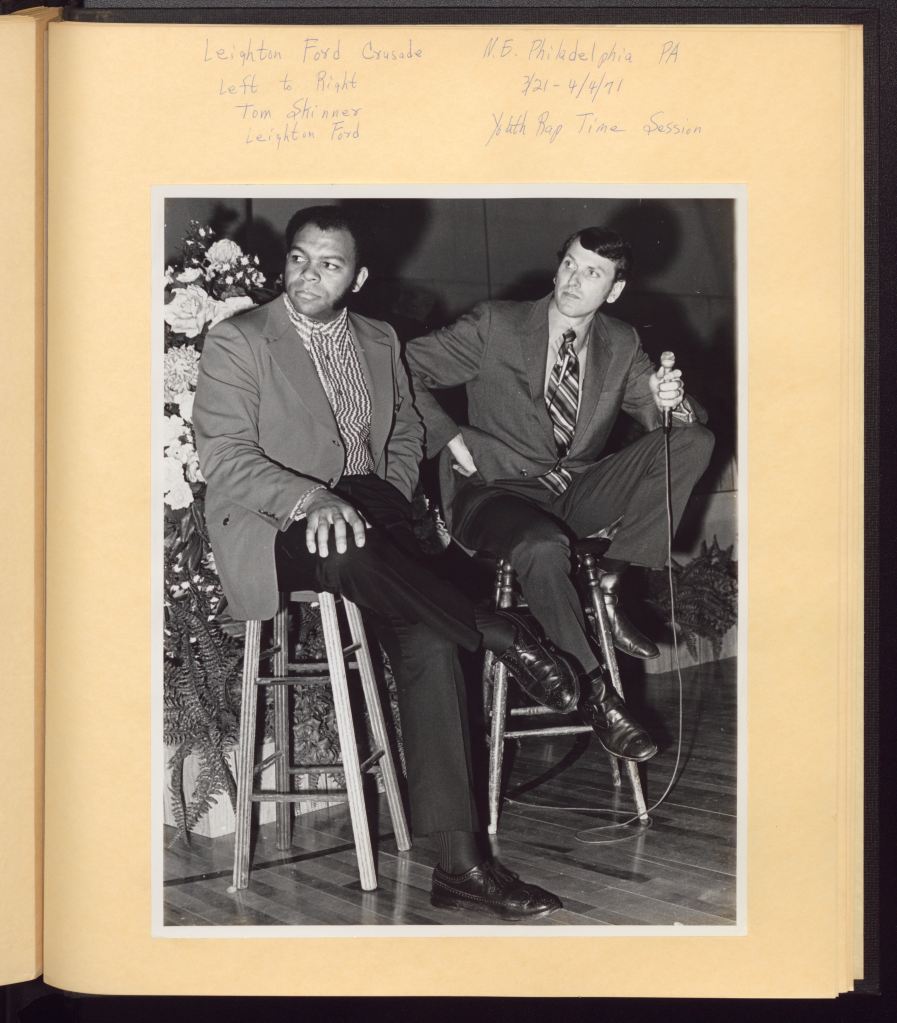

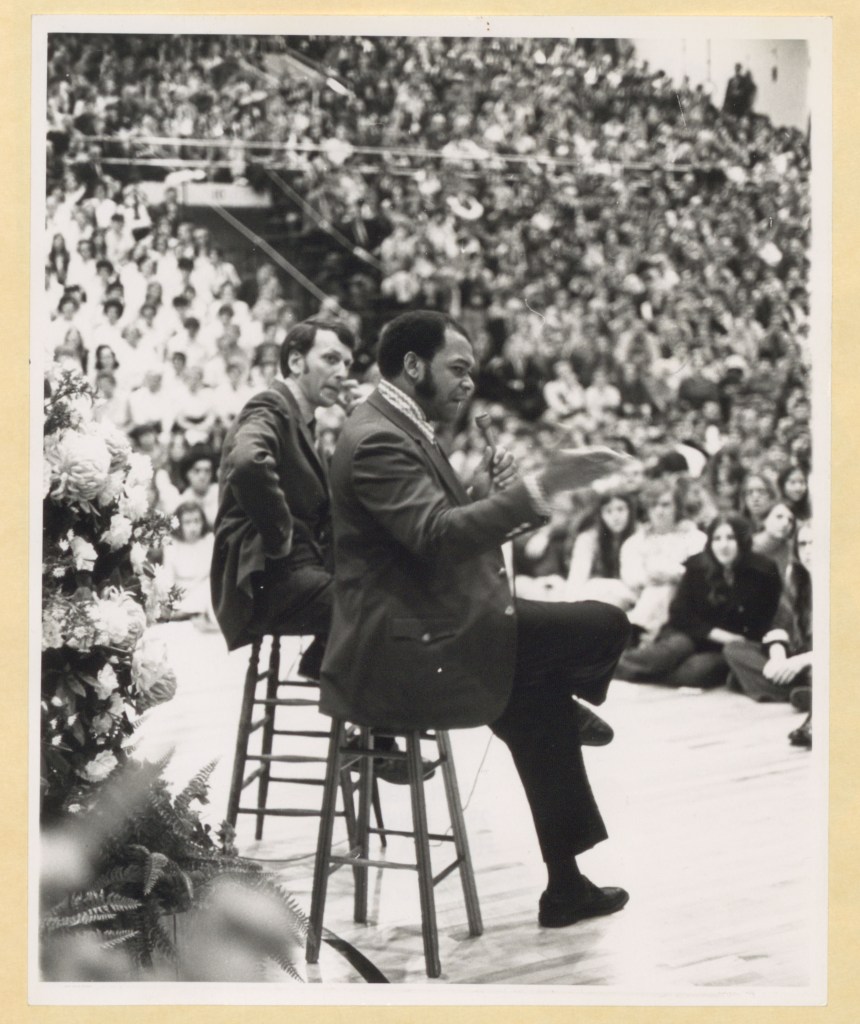

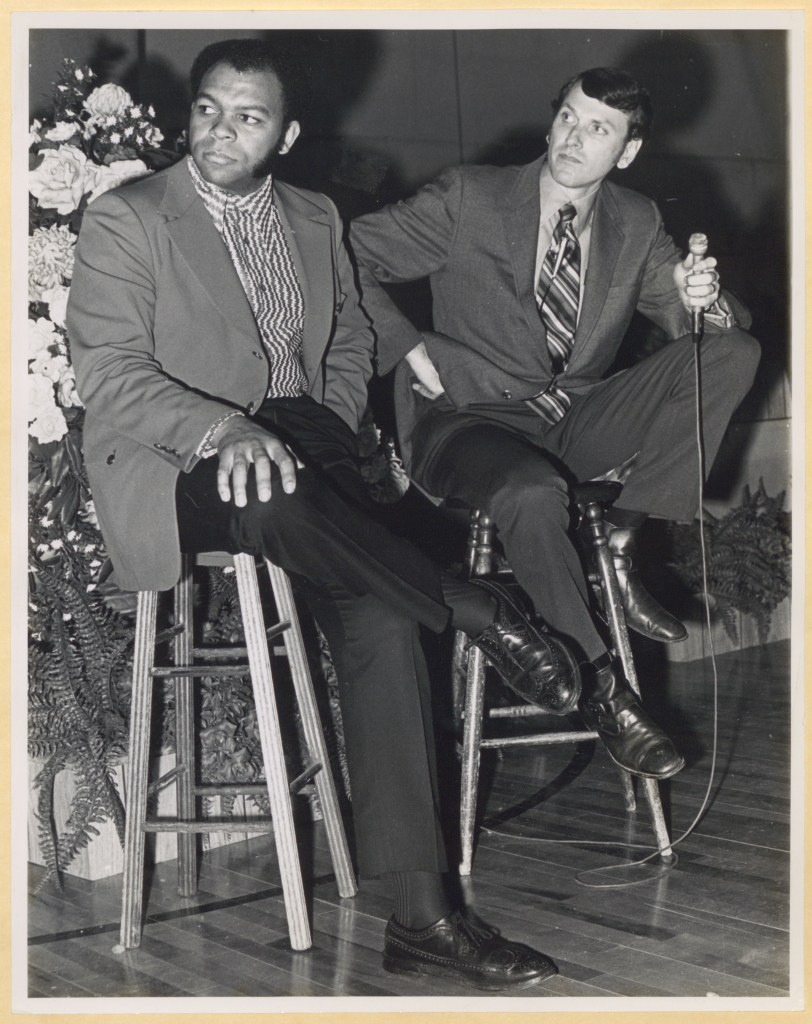

No one suggests that these two well-known figures could not have met or collaborated. However, only with the arranging and describing of Ford’s papers, including his crusade files, clippings scrapbooks, and photo albums did two photographs surface from Leighton Ford’s 1971 Philadelphia Crusade. Until this photo album was opened, we hadn’t known that Skinner and Ford had worked together, shared the stage, and combined their efforts to minister together to young people on Friday April 2nd. (Skinner’s appearance with Ford followed just a few months after his plenary address to InterVarsity’s 1970 Urbana Student Missionary Conference on December 28, 1970, on “Racism and World Evangelism.”) Ford’s report (Collection 738, Box 50, Folder 10) at the time of the campaign recalled this Philadelphia collaboration:

Tonight I spoke on “Love Is a 5-Letter Word.” 5800 – 104 inquirers. Tom Skinner was with us and gave a really fine testimony. He and I shared questions – again we felt the q-a went too long and didn’t really contribute a great deal to the service. It’s obvious that Tom has a real message for the kids.

Ford used this same model of joining forces when he appeared at the University of Virginia mission in mid-March 1972 in Charlottesville with Skinner and folk musician John Fisher. In Ford’s 2025 oral history interview (Collection 738, Tapes T5), he recalled this collaboration with Skinner.

INTERVIEWER: So, we have a photograph of you and Tom Skinner on the platform, in Philadelphia I think, probably during one of your …

FORD: It … it’s quite …

INTERVIEWER: … reach outs?

FORD: … it’s quite possible, quite possible. But the … more than that, they’ve just … you know the Christian study centers they have the universities? UVA, Virginia has one there. I was asked to go and lead a series in 1973 or ‘74 at UVA.

Adding to this in his 2023 interview (Collection 738, Tape T3), Ford remembered:

And so … but they said the typical evangelism has an aura to it, you know, an idea, caricature. So, we’ve got to find different ways to reach them. So, I said, “Well, I want you to give out questionnaires in the campus before we ever get there and ask people to finish this statement: ‘When I think of Christianity, I think of what? Blank.” So, they got thousands of those. Then I said, “We’re going to have a tricolor team. It’s going to be myself, Tom Skinner, the Black evangelist and John Fisher, the folk singer. And when we got up there and you know, this radical evangelist, Black evangelist Tom, and John, who with his beard and hair and glasses, wire-rimmed glasses was the counterculture, and me the WASP [White Anglo-Saxon Protestant]. And it blew the minds of some of those students.

Also in his 2023 interview, Ford reflected on his friendship and ministry with Skinner:

INTERVIEWER: Since you mentioned Tom Skinner, just your recollections of him.

FORD: Radical! Radical, bombastic Black preacher. But not just a Black preacher. I mean, he was … he was powerful! And I knew him and loved him. I think we had a great respect for each other. Made people mad, but he wanted to make them mad [laughs] …

INTERVIEWER: Yeah, yeah.

FORD: … you know, to get them to think, like Tony Campolo would at times. But he was … you know, he came from Detroit, Michigan. So, we grew up fifty miles from each other.

INTERVIEWER: Sure.

FORD: He was a great voice for the gospel. And I respected him. And it was great to team up with him.

And their stories continue. Skinner died at the relatively young age of 52, but his influence continues to be felt, and his imprint, especially on Black evangelicals, continues to bear fruit. Ford started his own organization in 1986 to merge his passion for evangelism with mentoring and developing young leaders, which he continues to this day.

As additional examples of the intersections, expected or unexpected, of other collections or documents, see several other Vault editions that refer separately to Skinner and Ford: