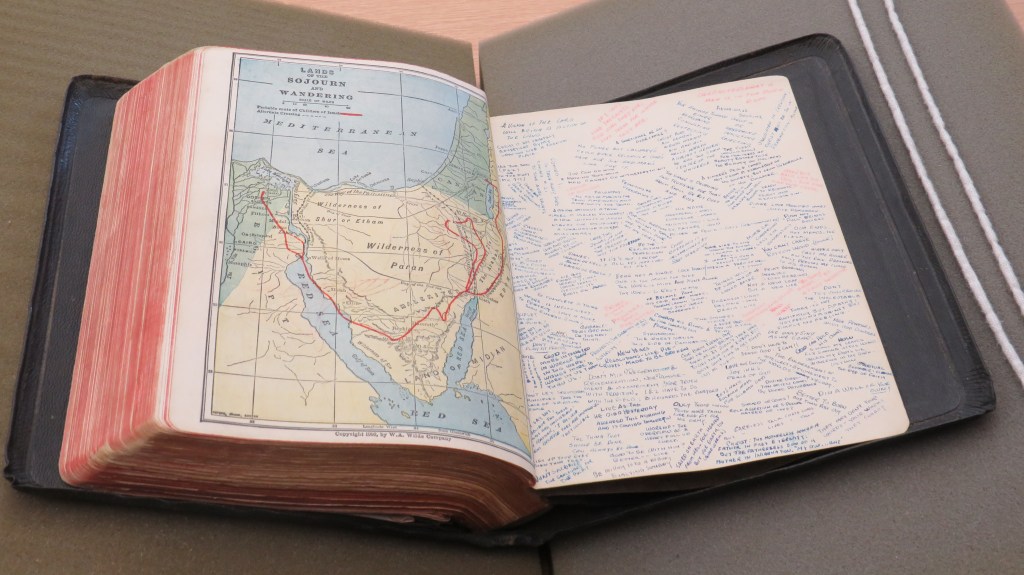

In November of 2024, Wheaton Archives & Special Collections collaborated with the Museum of the Bible to digitize Jim Elliot’s three college-era annotated Bibles held in CN 277: Jim Elliot Collection. After digitization was completed in February 2025, two archives interns, Ava Pardue and Mariah Sray, both part of Wheaton’s Aequitas Fellows Program in Public Humanities and Arts, spent the summer indexing all the annotations in the Bibles.

Ava Pardue just finished her freshman year at Wheaton. Along with being an Aequitas Fellow, she plans to major in English and Classical Languages. Mariah Sray is a senior at Wheaton with a major in Classical Languages integrated with Choral Studies.

Below, we feature an interview with Ava and Mariah about their work on the project.

What drew you to the Jim Elliot Bible project?

Ava: When I heard about the opportunity to work with Elliot’s Bibles, I jumped at the chance to engage with language, theology, and history in a way that could be useful to the public. One of the three Bibles is a Greek New Testament, which I was particularly interested in studying with the knowledge of Koine Greek that I’ve picked up during the last several years. And ultimately, I think the biggest thing that drew me to the project was a chance to look at Jim Elliot—a man hailed as a martyr, hero, and catalyst for modern missions—as an ordinary college student.

Mariah: An interest in exploring archival work drew me to this internship, but I was also curious to learn more about Jim Elliot. I knew the broad contours of his death in Ecuador but wasn’t familiar with the details of his life. I was also interested to how Jim interacted with his Bible, especially his Greek New Testament.

Could you give us an overview of your work during the internship?

Mariah: For this project, Ava and I catalogued the marginalia in Jim Elliot’s three college-era Bibles. We made notes in a spreadsheet every time he added a mark to any of these Bibles. This could be a note in the margin, a circle around a word or footnote, or an underline. We added additional context, finding the books and commentaries that Jim cites, filling out cross-references, and looking up the verses that Jim references.

Ava: Along with this work, we also transcribed many of Elliot’s letters to his parents, read practically every book published about Elliot and his wife, and went through 80-year-old yearbooks and course catalogues for background on their college years.

Did any particular annotations or passages or connections stand out to you during your work? If so, why?

Ava: Although the work could get tedious at times—flipping through long sections of Levitical law with no marginalia at all, or painstakingly researching the names of 20th century archaeologists—it was fascinating to uncover Elliot’s view of God through what he focused on in his college years. Occasionally, I stumbled across original poems or witty phrases, revealing a talent for writing that is corroborated by Elliot’s published journals and letters. One poem in particular stands out in my memory: it describes a mysterious “she,” in limbo between heaven and hell. I studied it for quite a while, wondering what Elliot’s thoughts on purgatory might be. Then I found a Bible verse marked next to the poem, and turning to it, I discovered that Elliot had been writing about Balaam’s donkey.

Mariah: I was struck by the lack of annotations in the later Bible. In 1948, according to Elisabeth Elliot in Shadow of the Almighty, Jim bought a new Bible, resolving not to make notes or underline it.1 (He must have later broken this intention, because it is now marked up, though mostly with underlines and cross-references, not with the same marginal notes as the 1945 Bible. Loose leaves found inside this Bible suggest he used it during his years in Ecuador). This purchase may have something to do with a chapel message given by Stephen Olford in January of 1948. Olford emphasized the importance of quiet time and keeping a spiritual journal.2 After Olford’s visit, Jim’s new journal, rather than his Bible became the primary place for him to note his thoughts on Scripture.

How did working so closely with Elliot’s Bibles affect your understanding of him as a person, a student, or a missionary?

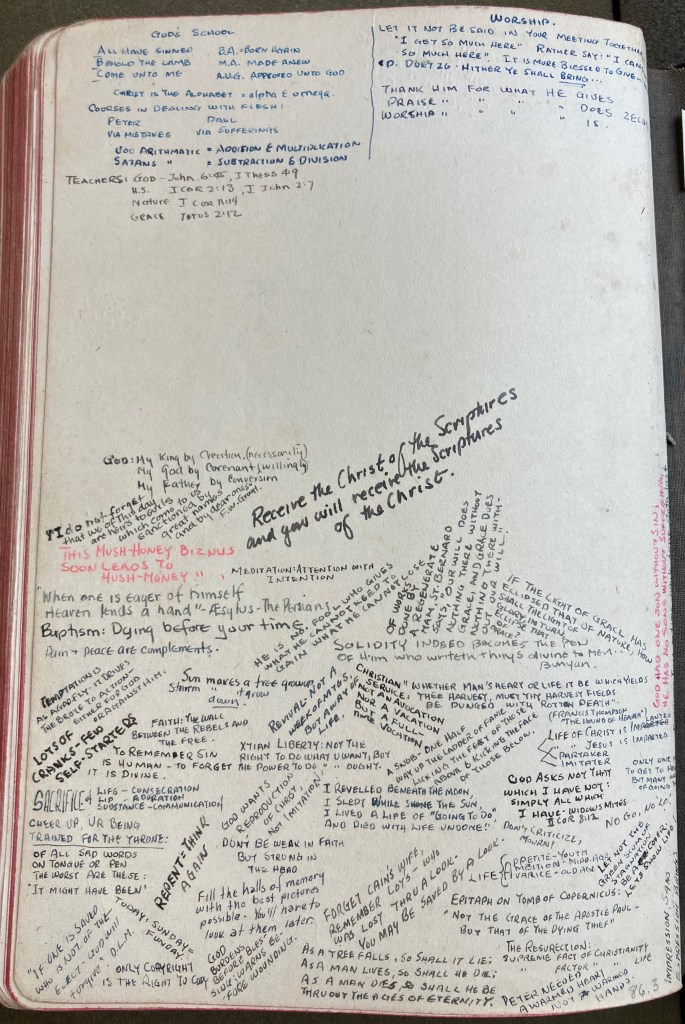

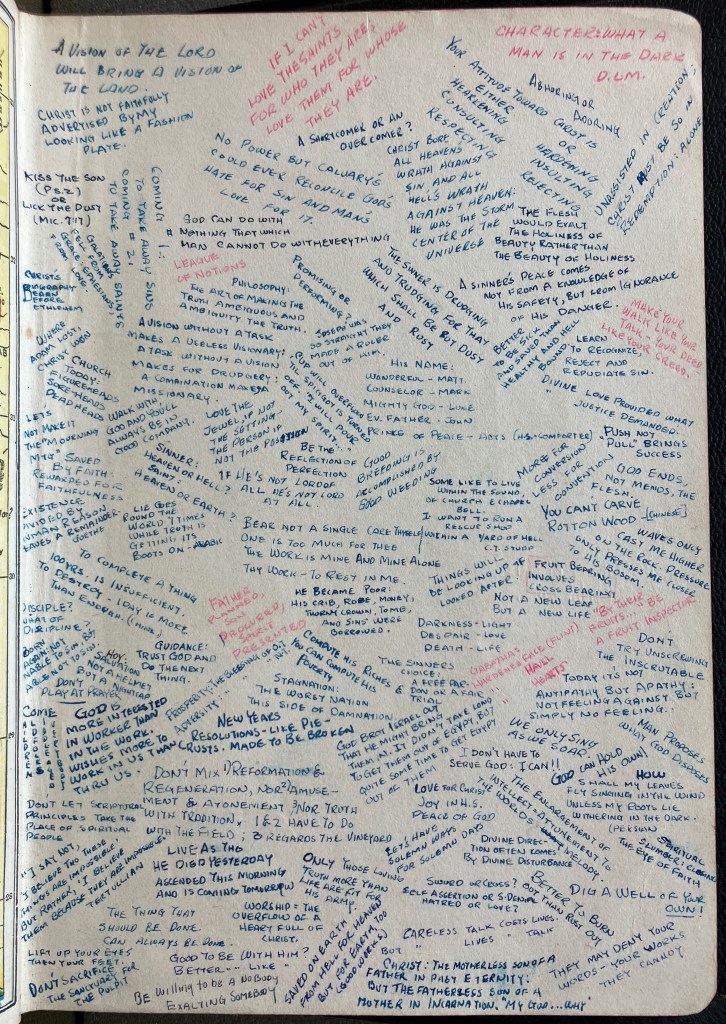

Ava: I appreciated the opportunity to observe Jim Elliot as a student. Surprisingly, much of the marginalia I catalogued seemed like things that could show up in any Wheaton student’s studies: from Old Testament notes, to chapel sermons, to definitions of difficult Greek words. Most of the spiritual insights tucked throughout the pages seem to be quotes or summaries of older theologians, rather than Elliot’s own groundbreaking ideas. Even his most famous axiom, “He is no fool who gives what he cannot keep to gain what he cannot lose,” originates with a 17th century Bible commentator. It is tucked on the back page of his oldest Bible, along with dozens of other quotes from writers and speakers he admired.

Some might be disappointed at Elliot’s reliance on more mature Christians for his spiritual insights. We expect someone so renowned to have his own grand epiphanies, independent of mundane study. However, it was only through being steeped in this theological tradition that Elliot was able to become the man who died in Ecuador. Throughout his college years, he writes to his parents about the range of theologians he is studying, from Amy Carmichael to C.S. Lewis. Immersing himself in the wisdom of the past was, for Elliot, the best way to hone his exegetical skills.

And indeed, Elliot did grow to make his own impact on the Church. Before his death, he preached everywhere from Wheaton to Portland to Quito. He possessed unusual charisma, and never failed to remind those around him of evangelism’s importance. As a result, he influenced a host of young men and women to enter the mission field. And after his death, Elliot’s emphasis on victory in Christ extends in his published journals and letters, continuing to change Christians’ lives.

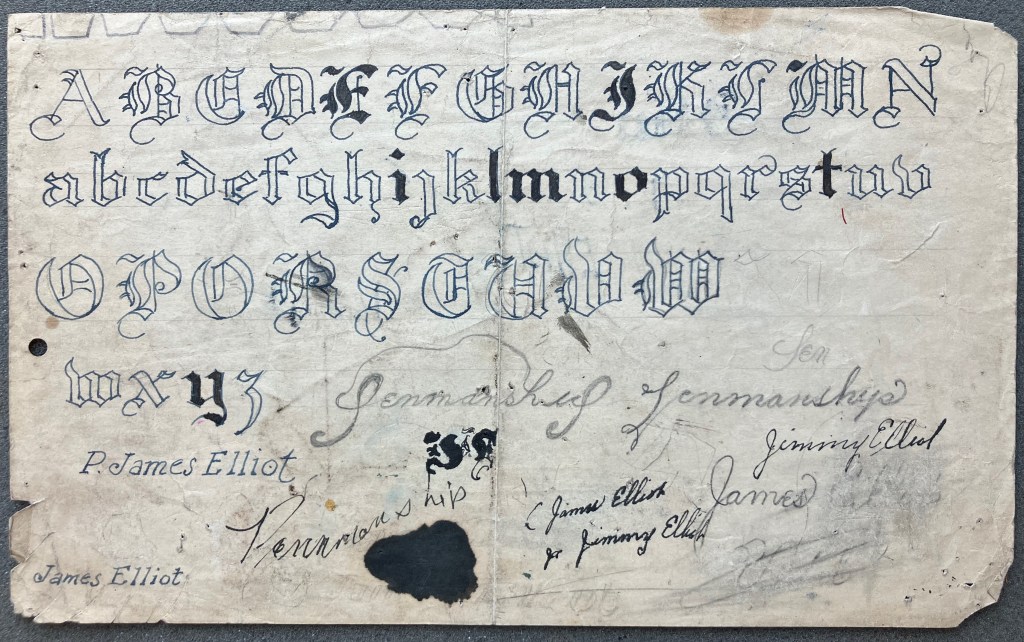

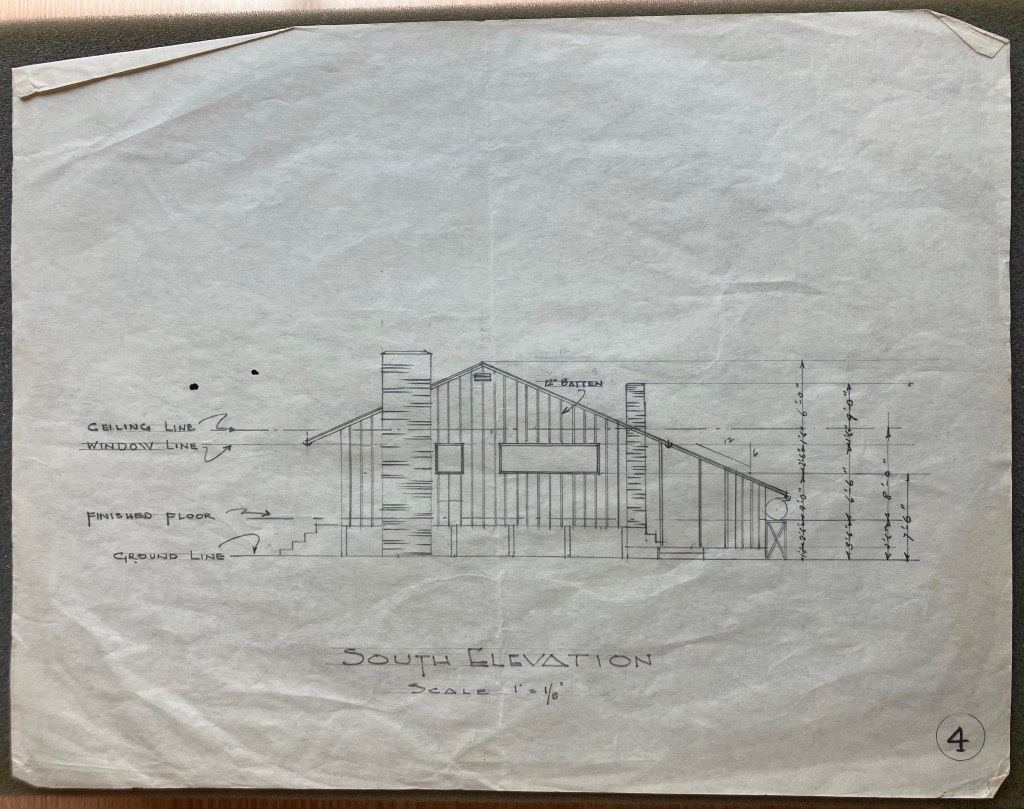

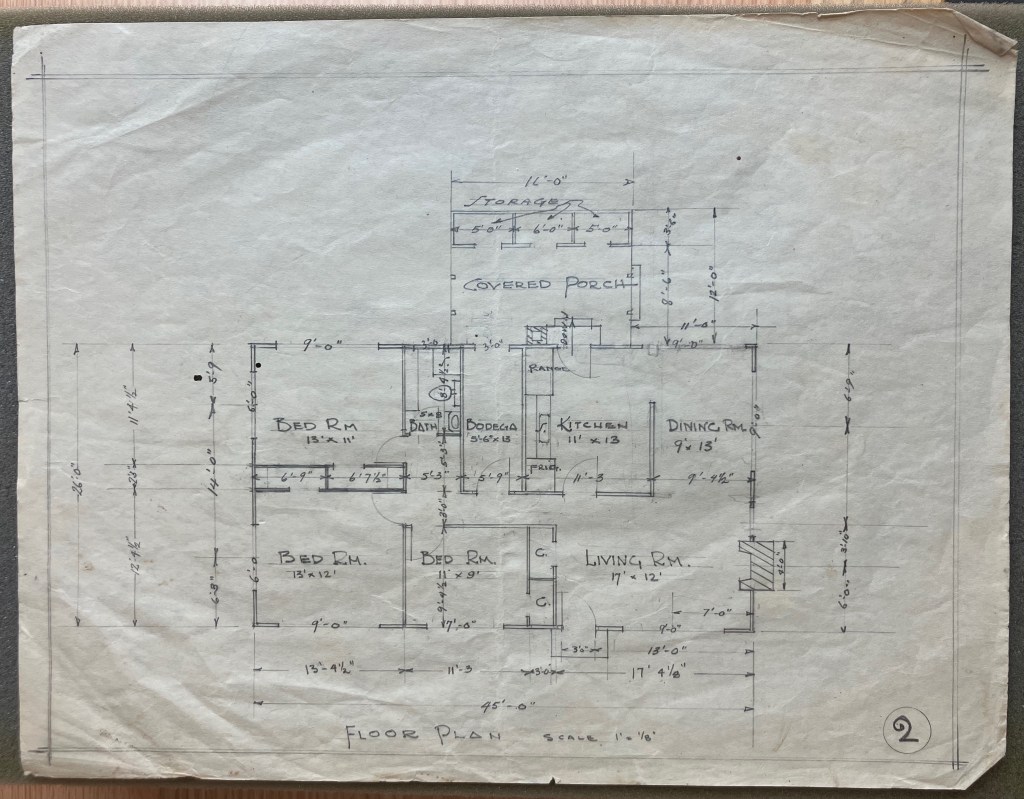

Mariah: One of my first questions after a cursory inspection of one of the Bibles was, “Did Jim have any artistic training?” Well, it turns out that he did. Jim attended high school at Benson Polytechnic High School and majored in architectural drawing.3 Among his papers is a sheet Jim used to practice a calligraphic alphabet. Elliot’s teacher apparently considered his drawings so good that she kept them for future classes.4 These skills served him well on the mission field – he drew up plans for the Elliots’ house at Shandia. But this artistic sensibility also pops up in Jim’s Bibles.

While Jim writes his letters mostly in cursive, his notes in the margins of his Bibles are almost exclusively printed. Most are written in a font similar to the block-capital preferred by architects and draughtsman. Jim shows care in making his notes neat, organized, and legible.

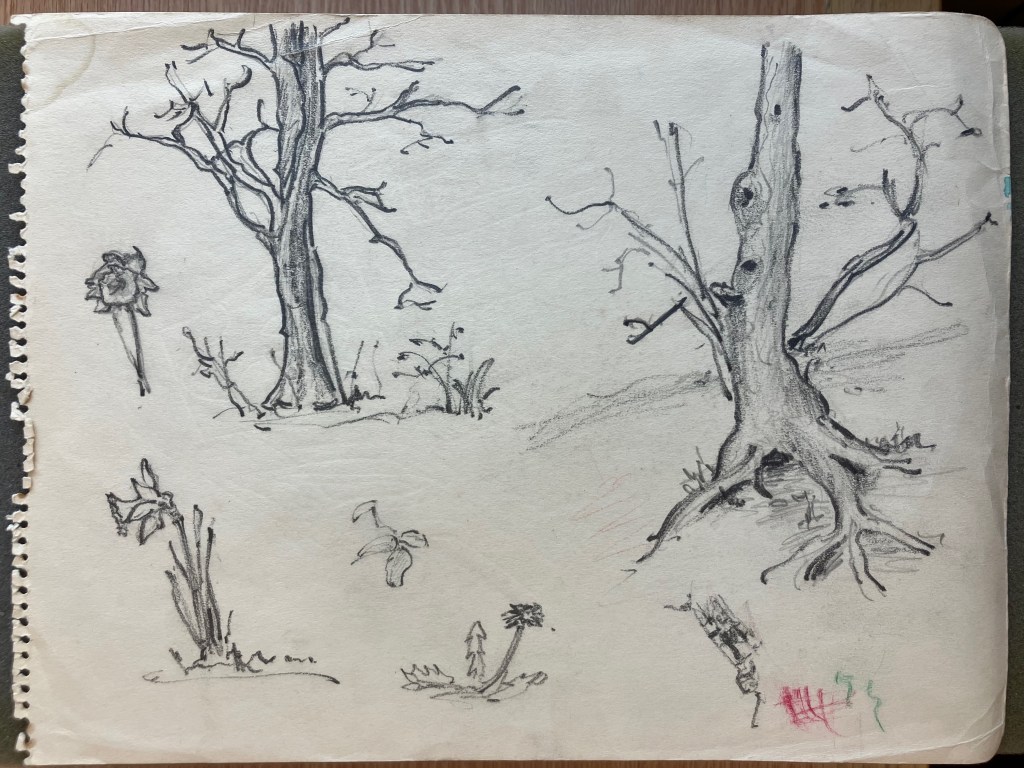

In a loose page from his 1947 Bible, Jim appears to be practicing his signature along with sketching boats. Jim’s earlier 1945 Bible includes a page of notes with a sketch of a compass. Jim’s papers also include sketches of a lion, studies of trees and flowers, and a rough sketch of a building, showcasing his artistic ability beyond the draughtsman’s precision.

Within his Bibles, Jim’s artistic tendencies appear more subtly. The most interesting artistic feature is his collage of quotes and pithy statements in his 1945 Bible. Quotes include Copernicus’ epitaph, Aeschlyus, Tertullian, Bunyan, and C.S. Lewis, offering a window into Jim’s reading life. Other phrases are unidentified and probably created by Jim himself. A few of these are particularly noteworthy for their intentional design. In these examples, Jim plays with fonts and lettering, using them perhaps as memory aids.

These artistic aspects of Jim’s marginalia show a different side of him that doesn’t make it into his famous missionary-martyr narrative. His journals, Shadow of the Almighty, and other sources portray him as a single-minded young man bent on making disciples for Christ (and occasionally critical of a Wheaton culture he saw as unserious!). But Jim’s Bibles with their architecturally influenced marginalia show that he had other giftings hidden beyond his passion for the mission field.

What aspect of archival work surprised, intrigued, or challenged you the most?

Ava: While working at the Archives this summer, it startled me to discover the range of treasures and documents that are stored here, but aren’t fully taken advantage of. On my initial tour around the building, I was told that anyone could request to see Elliot’s letters, or even his Bibles, and that the better part of materials related to Jim Elliot are housed in the Wheaton Archives. However, despite this wealth of information at scholars’ disposal, a scholarly biography of Jim Elliot has never been attempted. Instead, the books published about Elliot and the other men who died in Ecuador are either memoir accounts written by wives and friends, or hagiography meant to encourage children in the faith.

Mariah: One of the things I’ve come away with from my time at the archives is an appreciation for the level of organization. Each collection has a number, and the physical objects are filed in folders and boxes, also with their own numbers. This means that there is one place, and one place only for an object. Digital records reflect this system as well. Digitized versions and transcriptions are named with the date and put in digital folders named with an analogous system. I’ve already begun to create systems that have a digital component to track the movement of a set of items.

How did working with original materials impact the way you think about how we learn from the past or how you approach your own studies?

Ava: Although I don’t consider myself a historian, I regularly thrilled at the touch of these 80-year-old pages, and delighted in the puzzle of piecing together Elliot’s life and theology. For the first time, I realized the real value of retaining and studying historical documents. What had once been a vague, distant connection with a Christian hero became an intimate relationship with Jim Elliot and the culture that shaped him. I wholeheartedly credit this experience to the Archive’s constant work to collect and protect history.

What advice would you give to other students interested in archival work?

Ava: For those interested in joining the Archive’s work, I would suggest cultivating a love for history—both the people we tell stories about, and the documents we use to knit those stories together. As far as I can tell, among the people serving here, the greatest common denominator is a love for all the material they touch.

Mariah: Archival work requires patience, persistence, and attention to detail. Because of this, I’d advise giving your brain and body a break every so often. Stand up, walk around, and change tasks every so often. I’ve found this tactic key in making the tedious portions of archival work more enjoyable!

If you could work on another archival project, is there a collection or topic you’d love to explore next?

Ava: If I had more time at the Archives, I would be eager to dive deeper into Elliot’s story. Most of his letters remain untranscribed; boxes of documents from friends and family remain relatively unused. Jim Elliot’s scholarly biography has yet to be written, and I might be content to sit down and do the work of it myself.

Mariah: There’s a lot to study! My manuscript project has me continually fascinated with all objects medieval (for the past two years I’ve been creating a manuscript page, making the parchment, ink, quills, etc.). Two figures from Wheaton’s collections that pique my interest are Elizabeth Green and Hans Rookmaaker. Elizabeth Green was a conductor and educator who spent significant time at the University of Michigan in my hometown of Ann Arbor. And I’ve run across Hans Rookmaaker in my studies of art history and would love to learn a bit more about him. My recent explorations in the Wheaton Record have also sparked an interested in further diving into that collection.

- Elliot, Shadow of the Almighty, 51. There’s a bit of a mystery here. Elisabeth says that Jim bought the Bible in 1948, but Jim labels it “Jan- ‘47” on a flyleaf. One possibility is that Jim simply miswrote the year, forgetting that it was the start of a new one (1948). Another possibility is that Elisabeth remembered incorrectly, and the new Bible had nothing to do with Olford. The former seems more likely. While no complete records remain from Olford’s messages that week, quotes appear in the Record referencing his time at Wheaton. Oral history interviews with Dave Howard (Elisabeth Elliot’s younger brother) and Jeanette Thiessen mention Olford’s time at Wheaton as memorable. From these sources, it seems that Olford’s sermons prompted a small revival and emphasized total commitment to Christ, silence, and quiet time. His messages prompted both Jim and Elisabeth to start keeping a journal and may have influenced Jim’s decision to get a new Bible. See Jim Elliot, The Journals of Jim Elliot, ed. Elisabeth Elliot, (Baker Book House Co, 1978) 11-12; Elisabeth Elliot, Passion and Purity, (Fleming H. Revell Company, 1984) 22; “Chapel Nuggets,” The Wheaton Record, January 22, 1948, 2; “Munger Stresses Bible Teaching” and “Classes to Stop as School Prays,” The Wheaton Record, Thursday Feb. 5, 1948, 1; “Oral History Interview with David Morris Howard” by Paul Eriksen, Wheaton Archives and Special Collections, 24 March 1993, Accessed 10 July 2025, https://www2.wheaton.edu/bgc/archives/transcripts/cn484t02.pdf; “Oral History Interview with Jeanette Louise Martig Thiessen” by David Hammen, Wheaton Archives and Special Collections, 9 November 1983, Accessed 10 July 2025, https://www2.wheaton.edu/bgc/archives/transcripts/cn260t01.pdf. ↩︎

- Elliot, Passion and Purity, 22. ↩︎

- Elisabeth Elliot, Shadow of the Almighty, (Harper Collins, 1958) 28. ↩︎

- Elisabeth Elliot, Through Gates of Splendor, (Tyndale House Publishers, 1956), 16. ↩︎