This September marks the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II – A conflict that reshaped many aspects of American life, from industrial production and women in the workforce to urban migration and higher education. In commemoration of this anniversary, Wheaton Archives & Special Collections features photographs, clippings, and other materials from the Wheaton College Archives that document the experience of the Wheaton College home-front from 1941 to 1945.

Like much of the country at the start of 1941, Wheaton faculty and students were divided on America’s appropriate role in the European and Pacific wars. Debates on the growing conflict appeared in dueling opinion pieces in the Wheaton Record and as topics for lectures and featured speakers. However, for most of 1941, the possibility of America entering the war lingered only as a shadow over the busy routines of campus life. When the U.S. base at Pearl Harbor was attacked at the close of the year, the hypothetical quickly became reality. On December 8, 1941, students, faculty, and staff gathered together in Pierce Chapel to hear President Franklin Roosevelt’s special radio broadcast requesting a Congressional declaration of war.

Student Life in the War Years

Despite the official declaration, changes to campus life were gradual. On the first issue of the Wheaton Record after the reports of Pearl Harbor, President V. Raymond Edman assured the campus, “Our patriotic duty at the present time is to perform our routine duties to the best of our abilities.” (December 9, 1941). Faculty urged male students to stay their present course and the Wheaton draft board reported that no service classification changes were imminent.

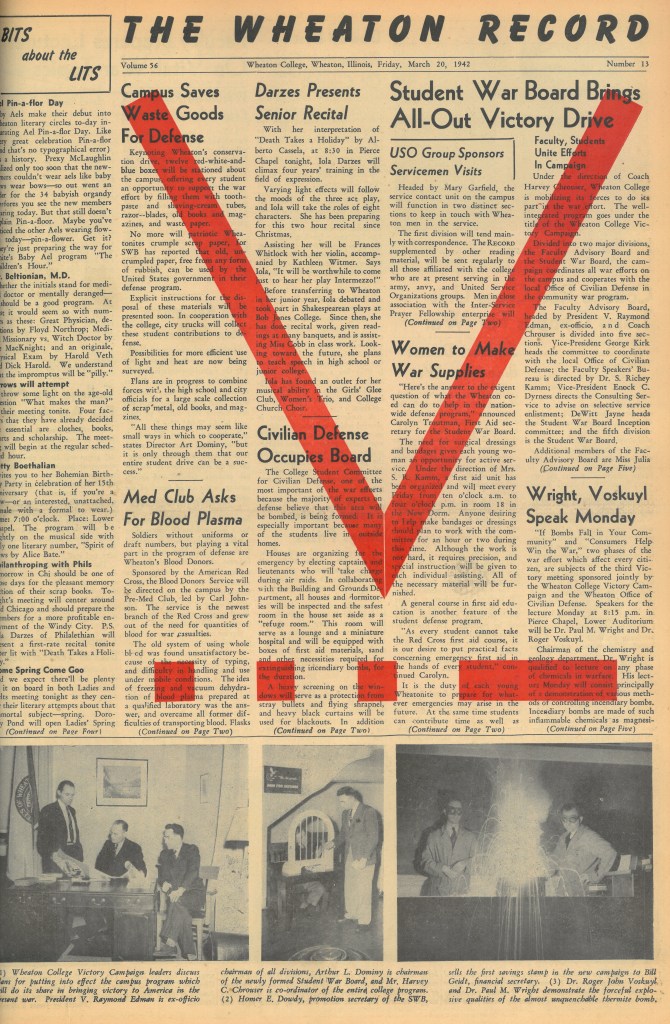

Although much of campus life continued as before – with classes, lectures, clubs, and other social events – the nation’s growing war preparations soon filtered into daily campus life. Musical programs, society dinners, and lectures were increasingly tinged with patriotic themes and fervor. By the spring of 1942, plans for official war activities had coalesced, with the College instituting a Faculty Victory Campaign Committee and a Student War Board. The Wheaton Record for March 20, 1942 recorded this growing war activity adorned by a bold red “V” on the front page.

By the 1942-1943 school year, war preparations had begun in earnest. In August, the campus experienced its first black-out, “Amid sirens, whistles, and air-raid alarms, Wheaton students with millions of other Midwesterners in the Chicago area hustled to shelter for the first black-out of this section” (Wheaton Record, August 18). To prepare for the worst, refuge rooms and shelters were set-up in the basements of student dorms. The Wheaton Red Cross Unit offered first aid classes for staff and faculty, and a student unit began to roll bandages for surgical dressings and knit cold-weather gear. Wheaton’s Pre-Med Club also ran campaigns for blood donation, promoting the new method of freezing and dehydrating blood plasma for use on the far-off front lines.

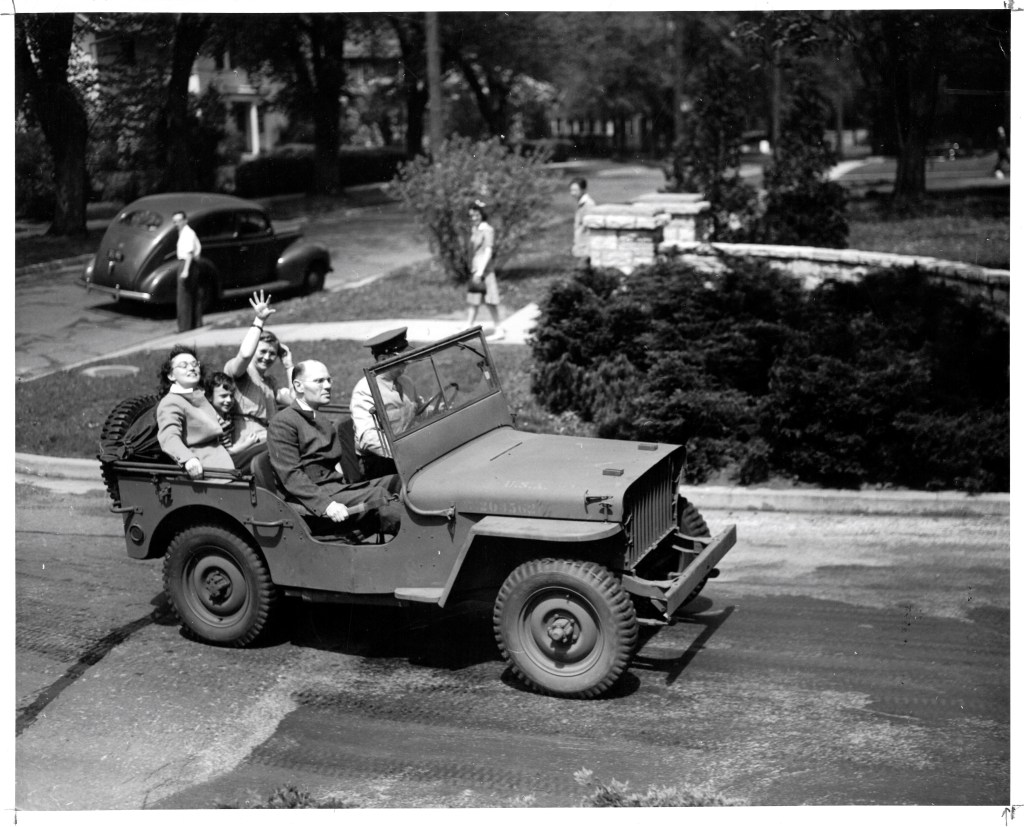

In addition to sourcing bandages, collecting scrap, and showing war newsreels, the Student War Board instituted new drives for the sale of defense stamps and war bonds. These efforts often involved creative poster campaigns, class contests, and community auctions (President Edman donated his bow tie for one memorable auction), as well as offering prizes like a spin in an Army Jeep for a $1 stamp sale.

War rationing also reached Wheaton. Coffee, tea, and sugar became scarce in the dining hall, and building projects stalled for lack of steel. Even the college schedule was affected in the winter of 1942, with the Christmas holidays moved two weeks earlier to accommodate troop movement on the railroads.

Despite the service exceptions for education and other programs, the 1943 Annual Report of the Registrar detailed an increasing number of withdrawals by male students for military service, totaling more than 100 since September 1942. Like the rest of the country, the departure of men for the battlefield created new opportunities and responsibilities for women students at Wheaton. By the 1943-1944 school year, even with a record high enrollment of more than 1200 students, women outnumbered men by 2 to 1.

As the war continued, women students helped organize first aid training, bond sales, and scrap drives through the Student War Board, the Red Cross Cadet Unit, and the Wheaton Literary Societies. They also ran much of Wheaton’s social life and increasingly stepped into roles vacated by the men who had left for service. After the original Wheaton Record editors were called away, students Charlotte Brown and Patricia Ann Cristy were named acting editors in 1942 and 1944 respectively, the appointments marking only the third and fourth time the editor position of the Wheaton Record was held by a woman in the Record’s more than 60 year history (Effie Jane Wheeler, the first female editor, was also a wartime appointment in 1918).

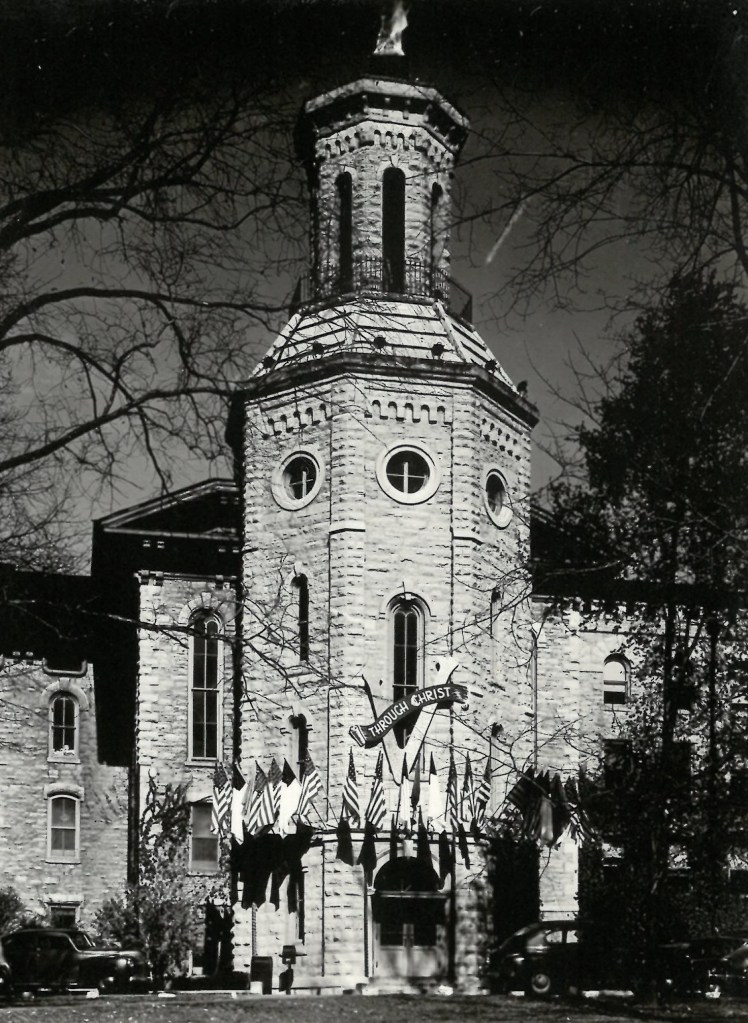

As more Wheaton students and alumni entered service through 1942 and 1943, the student Christian Service Council inaugurated the practice of ringing the Blanchard Tower bell each evening at 5 PM, calling everyone to a time of prayer and remembrance for Wheaton’s men and women in the military.

Liberal Arts in the War Years

Amid the urgency of war, Wheaton’s administration and faculty sought to balance new wartime projects with the College’s mission as a Christian liberal arts institution.

Addressing faculty on this point in the May 1942 Faculty Bulletin, President Edman wrote, “Let us take heed lest inadvertently we get some second or third degree academic burns during these stirring war days….It has seemed to me that we should lay stress on a mastery of our material, a mind to work, and a maintenance of civilian morale. In the midst of doing our job well, we should find opportunity for reflection as to how we can meet tomorrow’s problems after we have performed faithfully the duties of today.”

Following their respective masteries, Wheaton faculty instituted a “Victory Lecture Series,” with diverse offerings for “Good Health Will Win the War” from Dr. Russell Mixter (Zoology), “How Can We Pay for the War” from Mortimer B. Lane (Political Science), “Total Mobilization” from V. D. Jolley (Business Administration), “Our Government Organizes for War” from Richey Kamm (History), “Propaganda and Civilian Morale” from C. L. Nystrom (Speech), “If Bombs Fall on Your Community” from Paul Wright (Chemistry), “Music in the Nation Effort” from Mignon MacKenzie (Conservatory), and “Planning for Peace” from Orrin Tiffany (History).

Although determined to continue to promote the value of a liberal arts education, by 1943 the realities of war had reached nearly every department at Wheaton. Reporting on the changes in the May 1943 Faculty Bulletin, department chairmen from most of the humanities and arts departments outlined their efforts to combine or omit courses for the duration of the war, creating accelerated programs for junior and senior students. The government push for medical officers also led to a new two-year pre-medical course from the biology department.

While some departments contracted, the efforts of the Physical Education department were significantly expanded, with more emphasis given to student fitness and nutrition. The chemistry, physics, and mathematics departments also saw significant growth, both in program offerings and enrollment, with new classes on Celestial Navigation, Meteorology, and Chemical Warfare and Explosives.

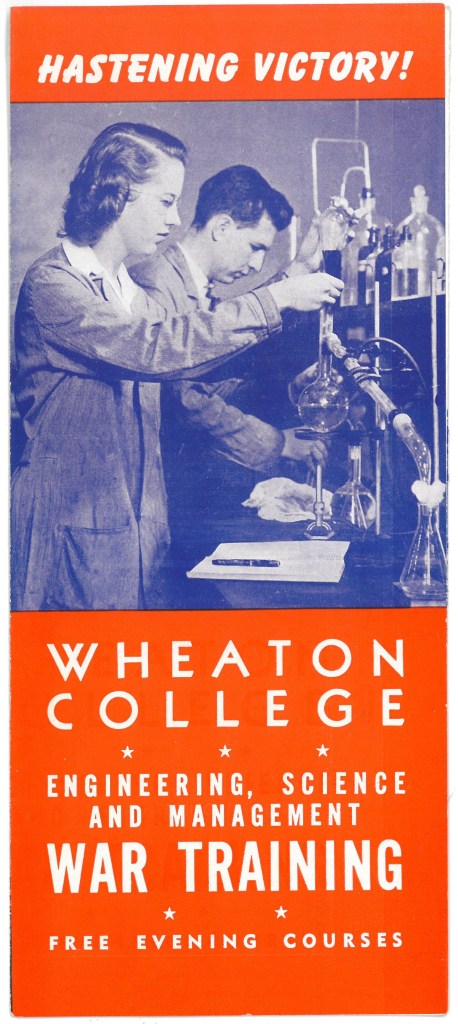

Additional night programs for technical education began in the fall of 1942, when Wheaton College was named one of eight colleges and universities in the state of Illinois authorized by the government to participate in a special war training program sponsored by the U.S. Office of Education. Through the program, Wheaton offered nine new college courses in the areas of Engineering, Science, and Management to those engaged in the war industry. The courses were open and free to all war workers, along with a limited number of college students in their final semester preparing for war work.

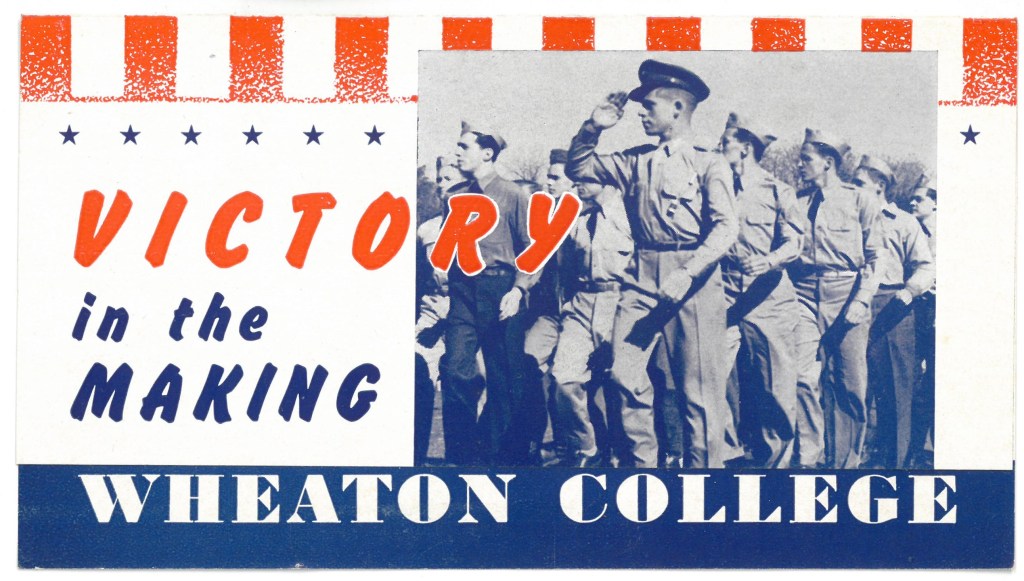

Army Specialized Training Program

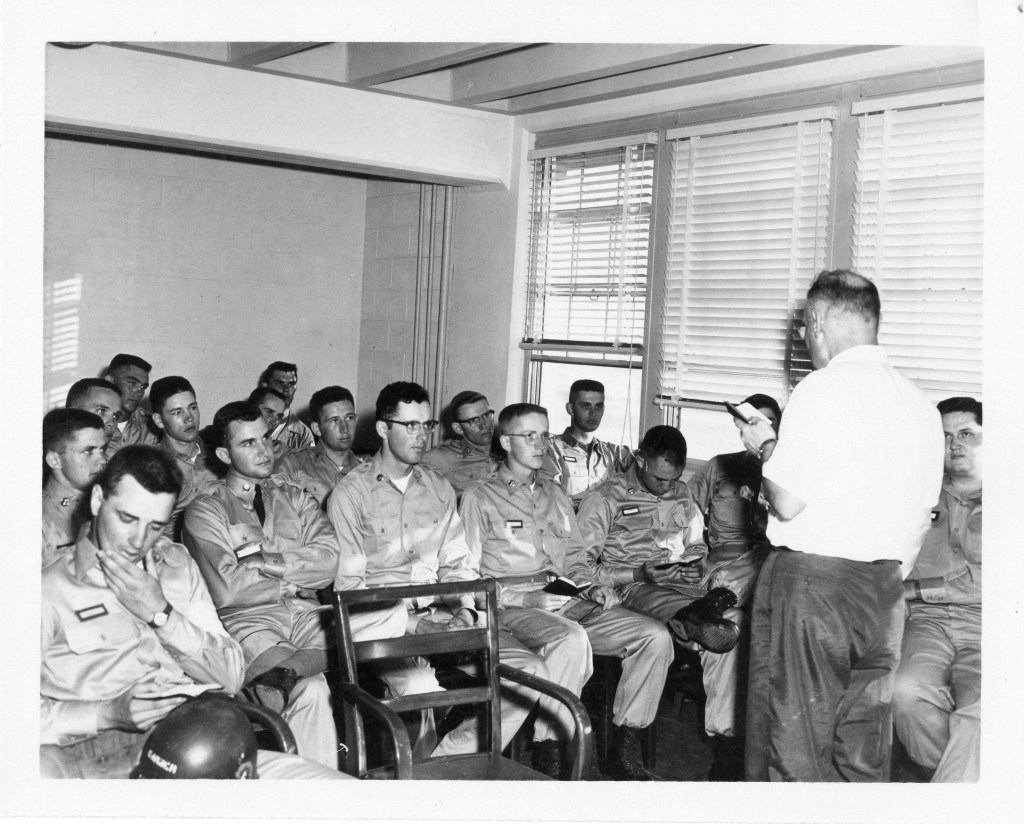

Along with student and college-run programs, Wheaton also hosted a special Army training unit on campus. During the summer of 1943, 250 soldiers arrived at Wheaton to begin Army Specialized Training Program 3672, otherwise known as ASTP. The program sought to meet the wartime demands for junior officers and soldiers by training skilled technicians and specialists. Headquartered in the old gymnasium (Adams Hall) the 20-dozen or so men were housed around campus and took their meals in the basement of Pierce Chapel. About a half-dozen faculty were involved in instructing these post-basic training soldiers, primarily from the Physics, Chemistry, and Mathematics departments. The Student War Board and other organizations planned joint events with the ASTP men, but relations between the two groups were often uneasy. Moreover, with Wheaton’s restrictions on dancing, cards, and alcohol, many soldiers sought to spend their free time in nearby Chicago. Due to the final pushes of the war and the need to replace soldiers on the front, the program was cut back and was withdrawn from Wheaton in April of 1944.

One of the soldiers stationed at Wheaton for supplemental training was John LaVine. Below are some of his recollections of his time at Wheaton, gathered by the Minnesota Historical Society.

“We finished our basic training…and was awaiting transfer to the Army Air Corps when my assignment to go to Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois, came through, to the ASTP unit there…. From Chicago we took, I think it was, the North Shore Line, an electrified commuter railroad up to Wheaton, to the college, and reported in there. Were assigned our billets, which were in the college gymnasium, and that was where about 50 of us slept on Army bunks, in Army fashion. Wheaton College was kind of a nice assignment. Wheaton was a fashionable Chicago suburb. I believe it still is. Wheaton College was, I believe, a Methodist school — [it had a] religious affiliation, anyhow. It was a small liberal arts school. The city of Wheaton was “dry” because of its college and Methodist background, so we had to go into Chicago, for the action, and so that’s where we did go. I think we went into Chicago only a couple of times, probably down on Clark Street, and so forth.”

“We were at Wheaton — I think it was winter semester, and then it was quite an engineering and scientific-oriented curriculum– it was not a humanities — and I think I had an Algebra test, and Algebra, although I’d had some in high school, really wasn’t my forte, and I did engage in attempting that famous dictum, a parody of “Victory through Air Power”, the slogan during World War II. I was trying “Victory with Eye Power” on an examination and got caught. If they’d had any sense they’d have bounced me out of the program, but I ended up walking a penalty tour al a West Point. We didn’t have our own weapons at Wheaton College. They had had an ROTC on it, and they had, I think, old Civil War muskets, that they’d fill the barrels with lead, and I was issued one of those — which must have weighed about 40 pounds — to walk around with on my shoulder for a couple of days. By this time, the needs for soldiers was acute with the increasing activity in the European theatre and the imminence of the invasion there, and also in the South Pacific, so the Army decided that it could not afford the luxury of the ASTP program, and so the program was closed down after that one semester at Wheaton College, and we were then returned to real life.”

Memorial Student Center

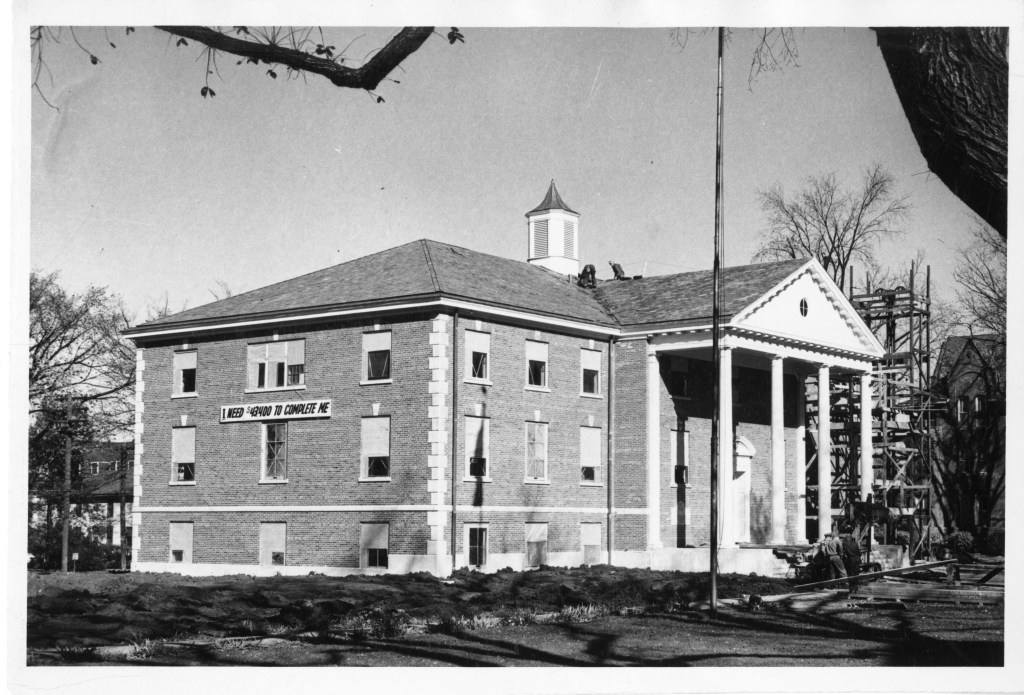

By the end of the war in September 1945, more than 1400 Wheaton students and alumni had served in one of the armed forces. Of this number, 39 died in service. To commemorate these students, the Alumni Association began a campaign in 1945 to raise $50,000 toward the building of the Memorial Student Center. The 1945 Armed Forces Tower, outlined the vision for the new building:

The Memorial Student Center is planned to end Wheaton’s shortage of dining hall space. There will be four dining halls and a magnificent, modern kitchen. The building will also house all the student organizations, the Tower, the Record, Student Council, Christian Council as well as the Alumni Association. The basement level will feature a large grill and fountain and a recreation room. There will be several comfortable lounges on the first floor. Small meeting rooms, private dining rooms, at least two literary societies and a devotional chapel designed to seat from thirty to forty people are included in the plans.

Completed in 1951, the Memorial Student Center is situated on the southern end of the quad. Although never used as a dining hall, for more than fifty years the building housed the STUPE, the Chaplain’s office, the Gold Star Chapel, and the offices for several student organizations. In 2007 the building was completely renovated to house the Business and Economics and Politics and International Relations departments. The MSC also holds offices for the Wheaton Center for Faith, Politics and Economics. The names of the 39 alumni and students who gave their lives in service are listed on a bronze plaque just inside the front door of the Center.

Explore more historic photographs, clippings, videos and other records on the history of Wheaton College through the College Archives.