This blog post has been adapted and updated from the Wheaton College Historical Review Task Force Report (pp 55-57), released on September 14, 2023. The entire report can be found here.

Every spring, Wheaton College celebrates Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month from April 15 – May 15, and this year the Wheaton Archives & Special Collections commemorates several Japanese American alumni who studied at Wheaton College during the turbulent years of World War II. The United States’ entry into World War II after the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 brought a wave of Japanese students to Wheaton College and with them questions surrounding the place of Japanese and Japanese American students both on Wheaton’s campus and in American society.

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, stipulating that civilians could be excluded from military spaces. Under EO 9066, the military began “evacuating” Japanese American residents from the West Coast the following month, first into temporary assembly centers followed by incarceration in camps supervised by the War Relocation Authority. Scattered over seven states, the 10 internment camps eventually housed over 122,000 Nikkei (Japanese immigrants and their descendants), the majority of whom were American citizens.

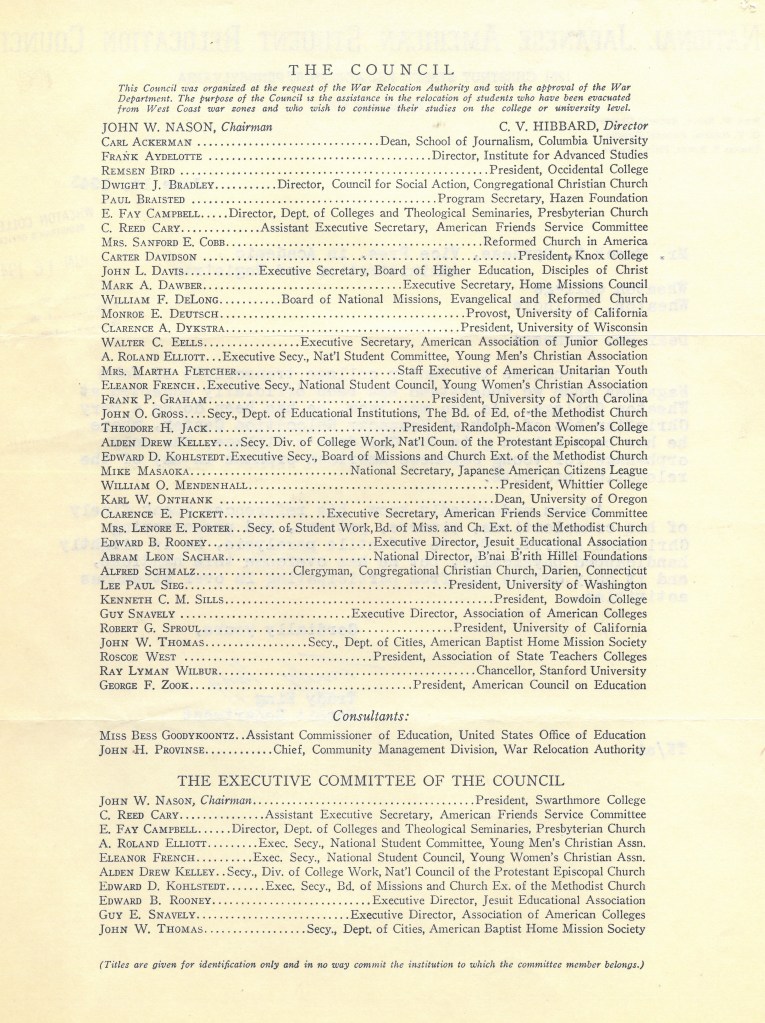

When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, approximately 2,500 Japanese American students were enrolled in colleges and universities on the West Coast, their lives and educations traumatically interrupted by the War Relocation Authority. To assist Japanese American students whose educations were interrupted, the National Japanese-American Student Relocation Council (NJASRC) was formed in May 1942 to place select college-aged students into higher education institutions east of the military areas. Candidates for placement were screened for “doubtful loyalty.” If cleared by the Council, students were transferred to participating institutions and enrolled. While some colleges and universities chose not to accept students out of the Relocation Centers due to anti-Asian prejudice, others advocated to bring Nikkei students to their institutions, working to provide campus housing, support from the community, and financial assistance in the form of scholarships. Although spearheaded by the American Friends Service Committee, the Council included a wide range of members, from college and university presidents and administrators to clergy representing mainline Protestant churches, to evangelical mission board executives, to the YMCA/YWCA.

“The Council was organized at the request of the War Relocation Authority and with the approval of the War Department. The purpose of the Council is the assistance in the relocation of students who have been evacuated from the West Coast war zones and who wish to continue their studies on the college or university level.”

The first wave of Nikkei students arrived at participating colleges and universities in the summer of 1942. By December 1944, over 3,500 Japanese American students, most of them second generation citizens, had enrolled at colleges and universities around the United States, including Wheaton College, Illinois.

While Wheaton’s student enrollment records from the wartime years are sparse, student files confirm that the College witnessed a notable increase in Asian American enrollment starting in the fall of 1943, specifically due to an influx of Japanese American students. Over the previous decade, Wheaton’s Asian American student population had hovered around one to two students per year, but in 1943, the number of Asian Americans enrolled at the College jumped from four to twenty, reaching a decade high of twenty-two students in the 1944-45 academic year. While it is impossible to verify if every student in this group was routed to Wheaton through the NJASRC internment camps, admission records confirm that Wheaton College did participate in the program and welcomed Japanese American students to campus beginning in 1943. While student files can be frustratingly sparse on details, they do provide a brief demographic snapshot of Wheaton’s wartime Nisei alumni. Between 1943 and 1945, the College enrolled a handful of Japanese American students, both men and women, from Hawaii and War Relocation Camps in the continental United States. This wave of enrollment continued through the war years until 1950

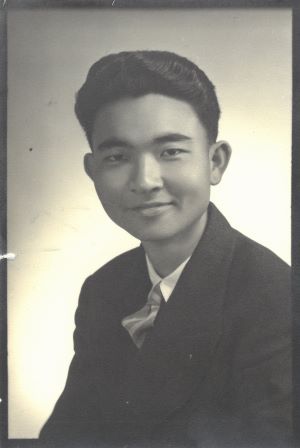

Kuroda Akira (1914-1997)

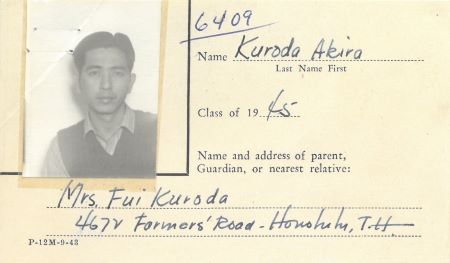

Of the first documented Japanese American students to arrive at Wheaton College from an internment camp was Kuroda James Akira. Kuroda’s application materials in his student file provide a fascinating glimpse into his journey to Wheaton. Born in Hawaii, he relocated to California to attend college after graduating from McKinley High School in Honolulu in 1932. Between 1936 and 1942, Kuroda studied at Pacific Bible College, Los Angeles City College, and finally Pasadena College, where he was a senior when the United States entered World War II.

Kuroda’s student file provides only the scantiest details about his internment. His Wheaton College application, dated December 20, 1942, lists the Granada Relocation Center in Amache, Colorado as his permanent mailing address, underscoring that Kuroda’s final semester at Pasadena College was abruptly cut short after the attack on Pearl Harbor in his hometown of Honolulu. “I was a senior when evacuated,” he wrote in his application form, a haunting reference to a life interrupted.

The smallest of all the relocation centers, Granada was overwhelmingly populated by Japanese Americans from California. Popularly known as “Camp Amache”, Granada opened in August 1942 and eventually swelled to over 7,000 residents.

The United States National Archives and Records Administration’s (NARA) database of Records About Japanese Americans Removed During World War II provides personal descriptive data about thousands of Japanese Americans who were evacuated from the West Coast and incarcerated in 10 internment camps spearheaded by the War Relocation Authority.

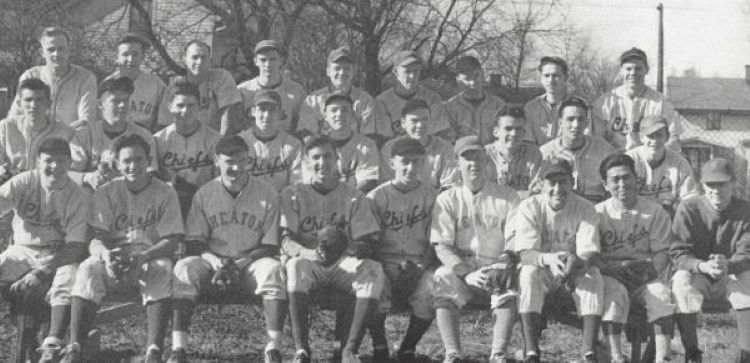

Wheaton’s admissions applications in the 1940s were light on personal information and essays describing an applicant’s desire to attend Wheaton College, but a few notable details illuminate the convictions that led Kuroda to enroll at a small Christian liberal arts college in the Midwest. Kuroda writes in his application that he had been a Christian for the past eight years and was a member of the Oriental Missionary Society, founded in Tokyo, Japan by American missionaries with roots in the Wesleyan Holiness tradition. He confided that he became interested in the College on the “[r]ecommendation of friends who attended Wheaton.” While the details of his friends’ “recommendation” are lost to history, it is likely that Kuroda was attracted the college’s explicitly Christian identity. He listed “Ministry” as his major of interest, and his entry in The Tower yearbook documents that he chose philosophy as his major and lettered in baseball.

Akira Kuroda matriculated at Wheaton College on September 14, 1943, and graduated in January 1945. In the following years, he continued his theological training at McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago before returning to Southern California.

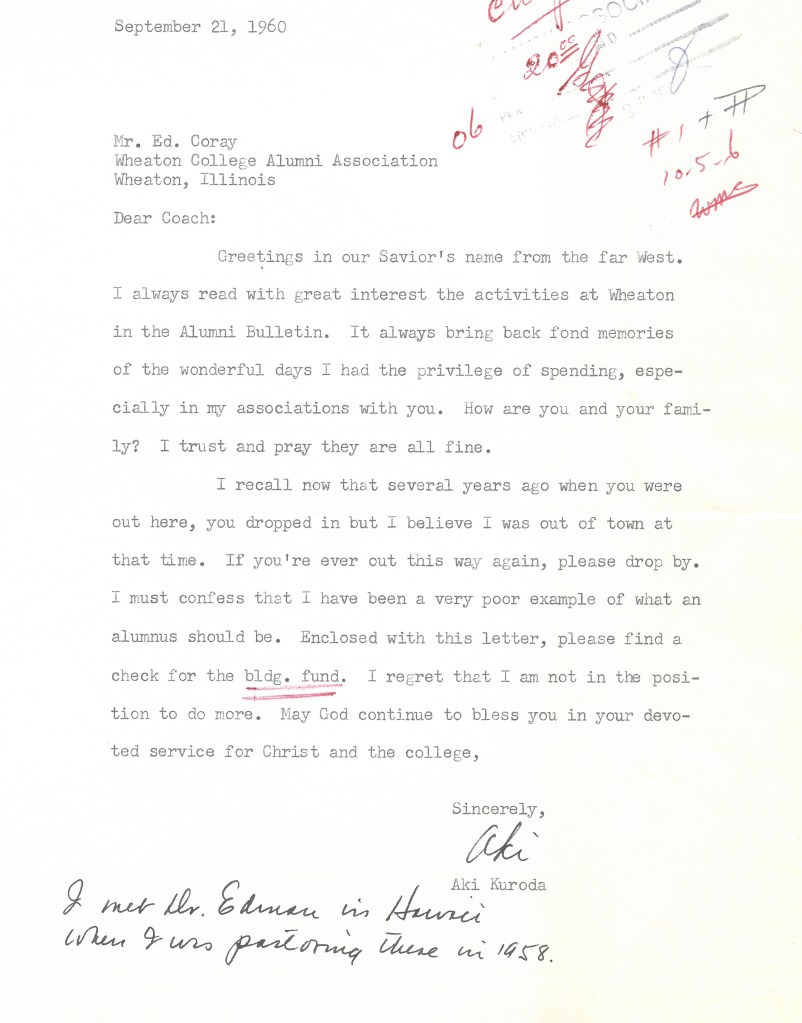

Kuroda apparently remembered his alma mater fondly and maintained contact with the Wheaton Alumni Association. In 1960, he wrote to the Alumni Association Director, and his former baseball coach, Ed Coray, affectionately addressing him as “Coach” and signing his letter “Aki.”

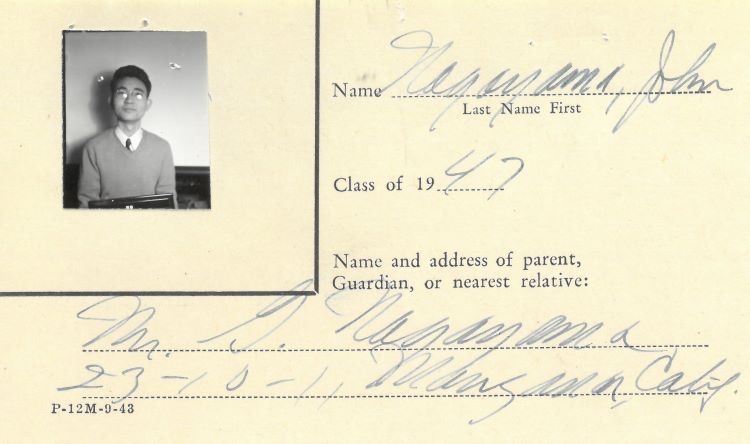

John Nagayama (1922-1977)

John Nagayama, another California native, arrived on campus the same semester as Kuroda but from a different War Relocation Camp. Nagayma graduated in 1941 from University High School in his hometown of Los Angeles, before attending Santa Monica Junior College. The cause for his abrupt withdrawal on April 6, 1942, is simply listed on Nagayama’s official transcript as “evacuation.”

The Japanese-American Internee Data File for John Nagayama at the National Archives offers a few additional details. Unlike Kuroda, John Nagayama was incarcerated at the Manzanar War Relocation Center on the eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California. The records are not clear about the transition, but Nagayama eventually found his way Manzanar’s Children Village, the only orphanage established as part of a War Relocation Center. Today the Children’s Village is included as part of the Manzanar National Historic Site preserved by the National Parks Service, but in 1942 it consisted of a few barracks housing Japanese American minors, including infants, from the West Coast. Some of the children were orphans while others were transferred from foster homes, rounded up after their parents had been interned in alternative Relocation Centers or simply declared unfit.

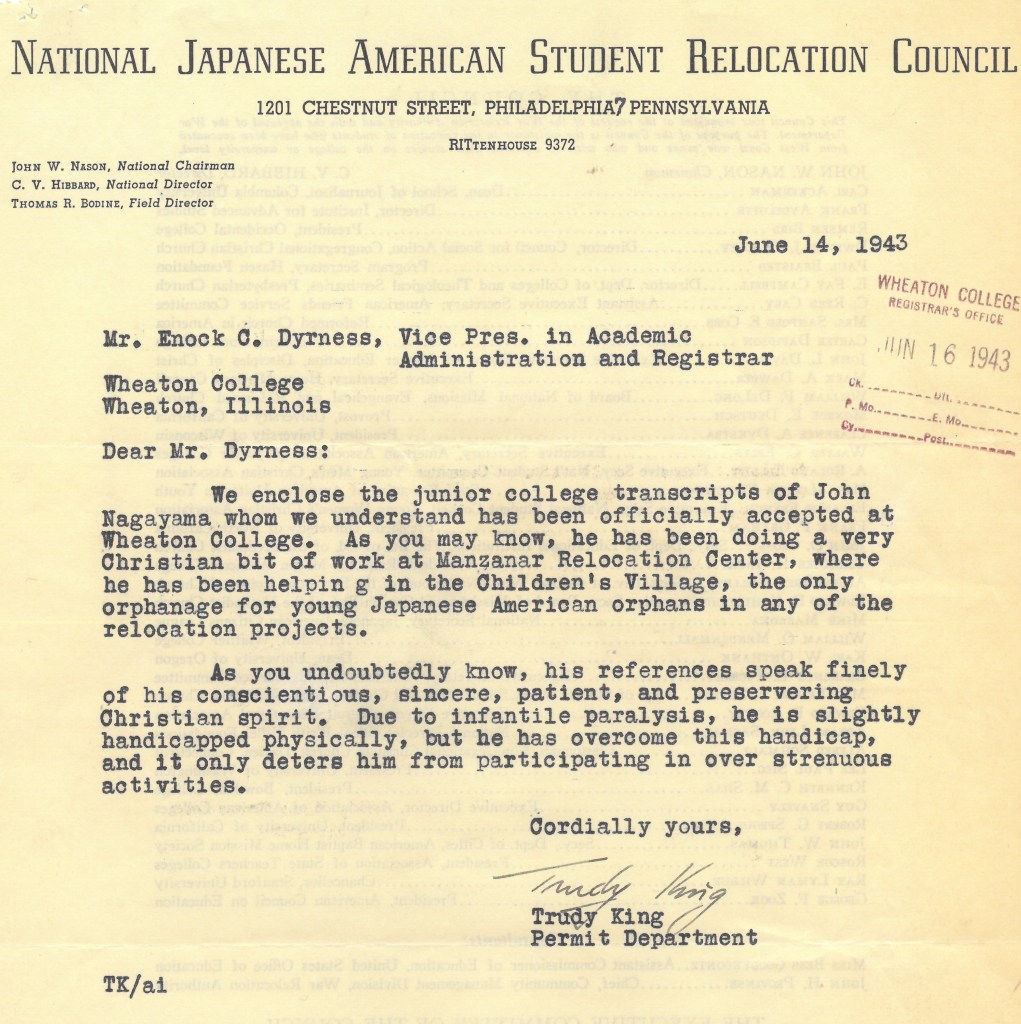

John Nagayama’s student file does not entirely illuminate how Nagayama—neither an orphan nor a minor—arrived at the Children’s Village in Manzanar, but a stray letter briefly mentions his activities at the Village and perhaps sheds light on the convictions that led him to enroll at Wheaton College months later.

In the spring of 1943, Nagayama applied to Wheaton College through the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council. His transcripts from high school and Santa Monica Junior College were accompanied by a letter from a NJASRC administrator to Registrar Enock Dyrness describing the “very Christian bit of work” Nagayama was doing at the Children’s Village and praising his “conscientious, sincere, patient, and persevering Christian spirit” reported by his references.

Nagayama’s Wheaton application offers only the briefest glimpse into his life before internment. Received on May 7, 1943 at the Wheaton College Registrar’s Office, the document confirms that Nagayama’s parents—both born in Japan—were also interned at Manzanar along with their son. Nagayama listed “Bible” and “Pre-med” as his major interests and noted that Wheaton College had been recommended to him by an unidentified friend.

As part of the faith commitments captured in the application, Nagayama indicates that he was a member of a Methodist church and has been a Christian for four years.

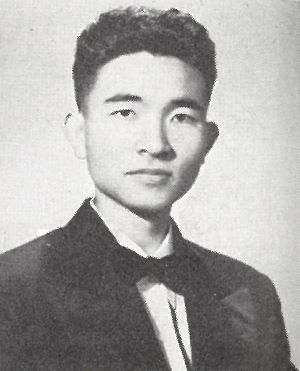

John Nagayama matriculated at Wheaton College in September 1943. Precious few details exist to flesh out his experiences at a small Midwestern liberal arts college, 2,000 miles from his birthplace. According to his transcripts, John Nagayama returned to California in the summer of 1946—likely the first time since his “evacuation” five years earlier—to enroll in summer courses at the University of Los Angeles, California. He chose, however, to return to Wheaton College to complete his studies, graduating in August 1947 with a B.S. in Zoology.

Despite his interest in the natural sciences, Nagayama may already have been planning for a lifetime commitment to Christian ministry. In a letter from the Director of Admissions welcoming Nagayama back to campus in August 1946, Albert Nichols alluded to the possibility. “We shall be ‘standing by’ to assist you in every way possible,” he wrote, “to that end that your continued work here may be a real credit not only to yourself and to the College, but more particularly to the One for whose service you now more fully prepare” [See RG 11-002, Biographical File 38-89].

Like Akira Kuroda, his Japanese American classmate at Wheaton College, John Nagayama spent years of his life in the pastoral ministry, sticking closely to both his California and Methodist roots. Biographical sketches retained by the Wheaton Alumni Association find Nagayama serving as an assistant pastor at a Japanese Methodist church in Fowler, California in 1957, a small agricultural city near Fresno. Sixteen years later another biographical sheet identifies Nagayama’s wife and three children as well as his then vocation pastoring Peninsula Free Methodist Church in Redwood City, California. At time of death in 1977, he was living with his wife in Phoenix, Arizona.

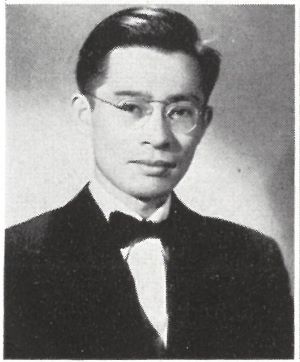

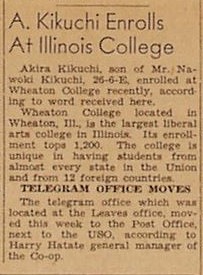

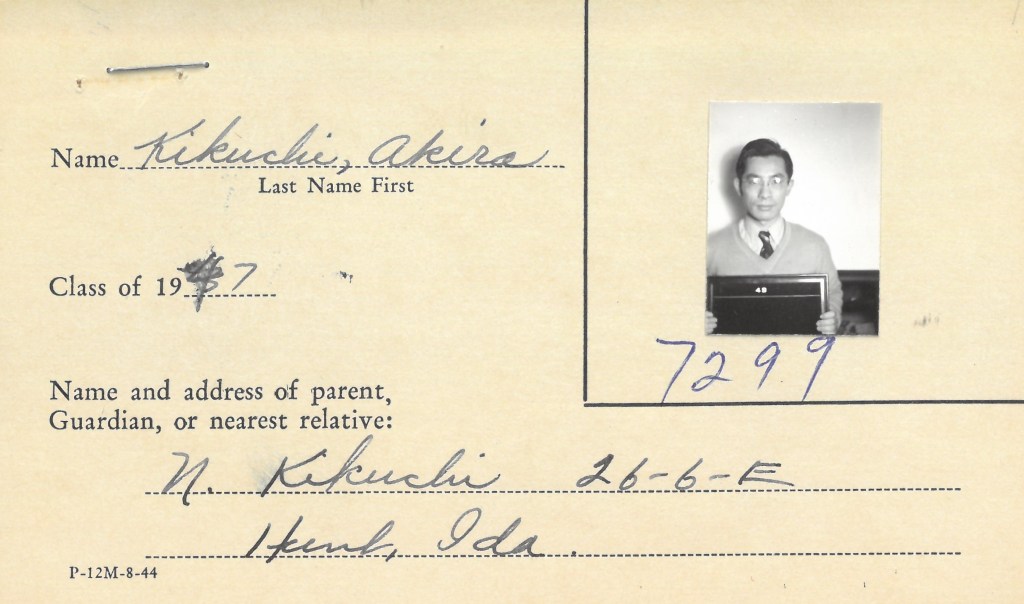

Akira Kikuchi (1916-2005)

Even fewer details exist about Akira Kikuchi, another Japanese American student who graduated alongside John Nagayama in 1947. Born in Seattle, Washington, Kikuchi graduated in 1939 from Broadway High School in his hometown and spent his freshman year at the University of Washington before being evacuated in the spring of 1942.

Kikuchi’s Japanese-American Internee Data File indicates Akira Kikuchi was held at the Puyallup Assembly Center, 35 miles south of Seattle. Euphemistically called “Camp Harmony,” the Center consisted of makeshift barracks on the Western Washington Fairgrounds outside the city of Puyallup. The Assembly Center opened in April 1942 and reached its peak population in July that same year with over 7,300 Nikkei. The exact date is unknown, but the Kikuchi family was eventually transferred to the Minidoka Relocation Center in Jerome County in southern Idaho. Overwhelmingly composed of Nikkei from Seattle, Portland, and other urban locations around the Pacific Northwest, Minidoka swelled to over 9,000 internees at its peak in March of 1943, not long before Akira Kikuchi applied to attend Wheaton College.

Kikuchi’s admission application is dated July 23, 1943, but he did not matriculate at Wheaton College until the spring semester 1944. A letter from Registrar Enock Dyrness in Kikuchi’s student file illustrates the challenges of applying to colleges from behind barbed wire. Dyrness writes to Kikuchi informing him that his high school credits met admission requirements, but his application was still lacking teacher recommendations, a certificate of health, a photograph, transcripts from the University of Washington, and the registration deposit of $25.00.

However, Akira Kikuchi managed to collect his necessary documentation, he arrived at Wheaton College on January 17, 1944 and declared English as his major. His student card depicts a serious, bespectacled man and lists his cell block at Minidoka (26-6-E) as his home address in Hunt, Idaho.

Like other Japanese American students who enrolled at Wheaton College through the NJASRC, Kikuchi’s admissions application documents a strong affinity for Wheaton College based on its Christian liberal arts identity. He identifies himself as a Christian “ever since childhood” and lists his denominational affiliation as Congregational. In a poignant letter to the Registrar’s Office, Akira Kikuchi wrote, “Ever since we [Nikkei] were evacuated from the West Coast, I am very concerned about our moral deterioration. So recently I decided to obtain some sort of religious training so that I might be able to uplift my people.” The NJASRC, Kikuchi writes, recommended Wheaton College.

Kikuchi worked steadily over the next two and half years to complete his education, enrolling in summer classes in 1944, 1945, and 1946 to earn his bachelor’s degree in August 1947. His senior yearbook entry lists no extracurricular activities alongside his English major, though other student records indicate that he attended the College Church and lived in a red brick house, still standing today at the corner of E. Forest Avenue and N. President Street today.

Akira Kikuchi all but disappears from Wheaton records after his graduation. His transcript request forms indicate that he remained in the Chicago-area, earning a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration in 1949 from Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Other alumni records from 1975 list Kikuchi as a resident of Detroit, Michigan.

However long he lived in the Midwest, Akira Kikuchi eventually found his way back to the Pacific Northwest, where he died in Portland, Oregon in 2005.

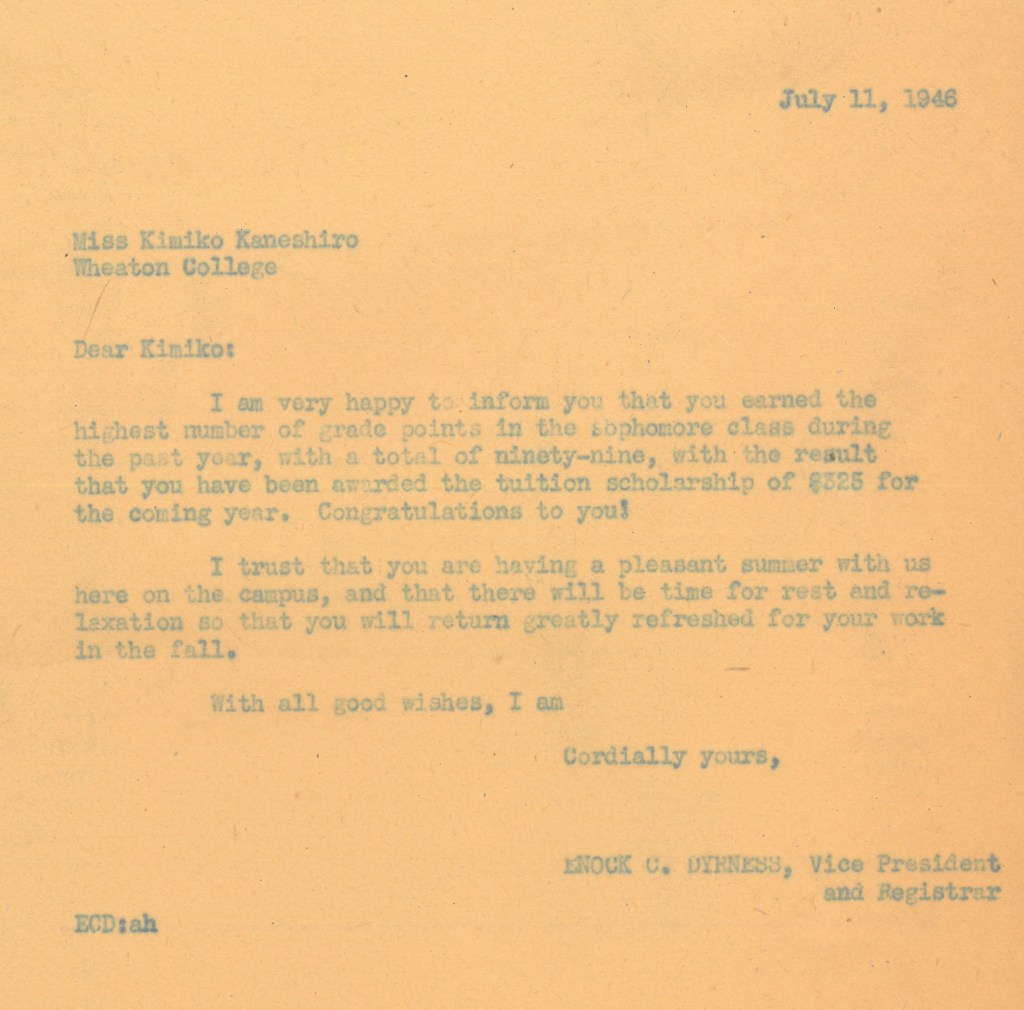

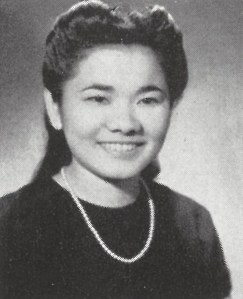

Kimiko Kaneshiro (1922-1982)

Not all of Wheaton’s Nikkei students came to the College from War Relocation Camps. Some were evacuees from Hawaii, like Kimiko Kaneshiro. Born on the island of Kauai to first generation Japanese immigrant parents, Kaneshiro graduated from Waimea High School in 1940, but it was not until 1944, nearly three years after the United States entered World War II, that she applied to attend Wheaton College, matriculating in September 1944.

Despite earning her B.S. in Botany at Wheaton, Kaneshiro was straightforward about her vocational ambitions following graduation. Her admission application dated February 10, 1944 states that she has been a Christian for five and a half years, her major field of interest is “Christian work,” and her denominational affiliation is Baptist. When asked her theological position on the person of Jesus Christ, Kamiko Kaneshiro switched from the typewriter to writing by hand, so she could squeeze in every last word of her answer: “I hold the Lord Jesus Christ, God’s Son and the Savior of the world in reverence, adoration, and worship. He, the Perfect One, in His great love to the world and me left His glory above to come into this sin cursed [sic] earth to pay the penalty for my sins. Accepting the shed blood of the Lord Jesus Christ, I am a child of His and now it is my privilege to tell others about Him.”

After matriculating in September 1944, Kamiko Kaneshiro completed her degree in a breakneck three years, including field work at the Wheaton College Black Hills Science Station and additional electives every summer semester. Kaneshiro’s transcript also reflects a single-minded focus on preparation for the global mission field. Her elective courses were overwhelmingly drawn from the social sciences, specifically anthropology and psychology. In addition to her studies, Kaneshiro participated in the Foreign Mission Fellowship on Wheaton’s campus, a popular student club for aspiring missionaries.

Following her sophomore year, Kaneshiro was awarded a tuition scholarship after earning the highest number of grade points of her entire class. Kaneshiro graduated with High Honor in August 1947 and set her sights to the mission field—Japan.

From her student file, readers today can follow Kimiko Kaneshiro from her Wheaton graduation across the globe. For the next 35 years, Kaneshiro continued to contact her alma mater, sending newsletters, announcements, photographs, and clippings to the Wheaton College Alumni Association to update friends and former faculty with personal and ministry news. From these bits and pieces, readers today can piece together a patchy portrait of her life after Wheaton College.

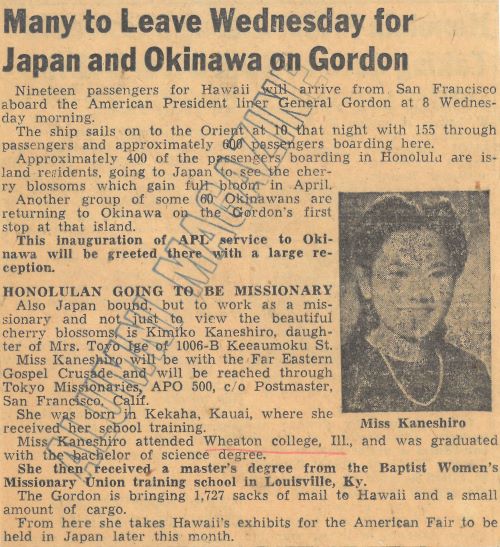

A fragile newspaper clipping in her student file sheds light on Kaneshiro’s post-graduation activities—she earned a master’s degree from the Baptist Women’s Missionary Union training school in Louisville, KY. Moreover, the clipping identifies Kaneshiro as a passenger on the ocean liner General Gordon sailing from San Francisco to Japan after stopping in Hawaii. Kamiko Kaneshiro is given an entire paragraph, highlighting her intentions to serve as a missionary in Okinawa with the Far Eastern Gospel Crusade (now Send International). A nondenominational missions agency, FEGC was incorporated in 1947 after developing from evangelistic work by American servicemen and women in Japan and the Philippines immediately after World War II. Kamiko Kaneshiro would have been among the first rounds of missionaries to begin service with FEGC in Japan. The faded newspaper clipping is stamped with “Alumni Magazine,” indicating that the office administrator filed it for potential inclusion in the Alumni Association magazine.

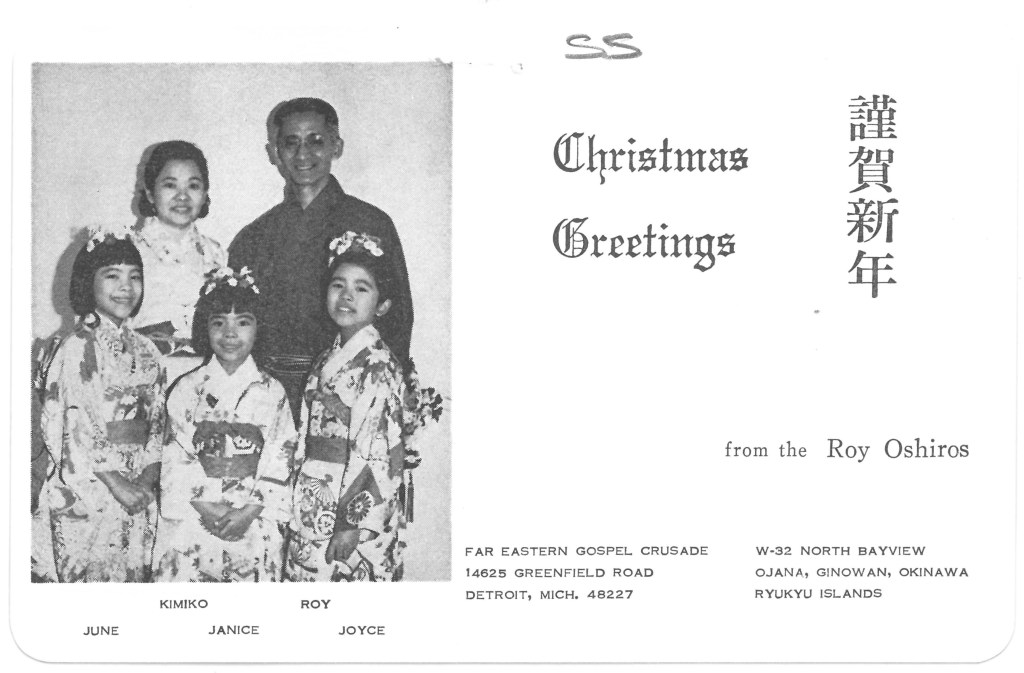

Kaneshiro did not just send professional updates to her Wheaton College contacts—her communications included significant personal changes as well. A large gap exists in her student file from her journey to Japan until when the Alumni Association received a wedding announcement from Yokohoma celebrating her marriage to Roy Oshiro, a fellow FEGC missionary in 1957.

Roy and Kamiko Oshiro, while raising their three children, continued to serve with FEGC for the next 25 years. Kamiko’s file contains prayer cards for the Oshiro family and articles on FEGC progress in Japan. Other documents confirm that Kamiko maintained ties with the College through the Wheaton College Scholastic Honor Society. Starting in 1973, the Alumni Association began receiving a typed newsletter from the Oshiro family. The office saved every update in Kamiko’s file until 1981, when the Alumni Association received a letter from the Oshiro children announcing their mother’s death on August 16 at the age of 58.

While no explicit details survive to document the experience of Japanese American students at Wheaton during World War II, College publications occasionally offer a glimpse into campus conversations about American citizens of Japanese ancestry. One subject was the perceived loyalty of Japanese immigrants or first-generation citizens. In the final months of the war, alumna Grace DeCamp (‘34) penned an article for Wheaton Alumni magazine, where she described her work as a missionary inside the Granada Relocation Center in Amache, Colorado. “Please don’t consider Japanese-Americans as different,” DeCamp pleaded, “They are as American as you or I, the difference being that they have to take a lot because of their ancestry” (Alumni Magazine, Jan. 1945).

Students like Akira Kuroda, John Nagayama, Akira Kikuchi, and Kimiko Kaneshiro likely would have faced prejudicial scrutiny from some members of the college campus, if not outright discrimination. After a freshman wrote an article in the campus newspaper targeting Japanese citizens and calling for genocide, Alumni Secretary Ted Benson, responded in defense of Wheaton’s Nikkei students: “His formula is neither Christian nor is it in the Wheaton tradition. We are proud of our graduates who are of the Japanese race and for those here on campus we say a hearty, ‘We’re glad you are here!’” (The Record, Oct. 11, 1945).

Additional Sources:

John H. Provinse, “Relocation of Japanese-American College Students: Acceptance of a Challenge,” Higher Education: Semimonthly Publication of the Higher Education Division United States Office of Education, Federal Security Agency 1, No. 8 (Apr. 16, 1945): 1-4.