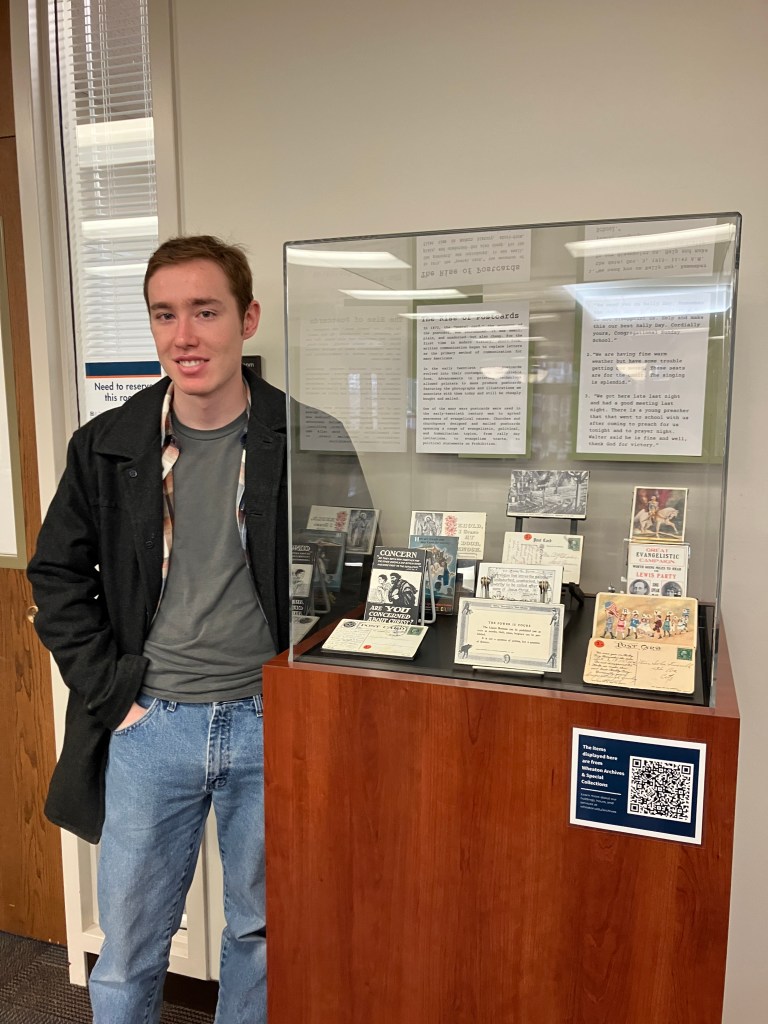

This week, Wheaton Archives & Special Collections shares a guest post from Andre-Ross Gennette, who is interning with the Archives this academic year. Andre-Ross Gennette is a junior at Wheaton College, dual majoring in History and Biblical and Theological Studies, as well as a Wheaton Aequitas Fellow with the cohort for the Fellowship in Public Humanities and the Arts. Along with his work processing Wheaton College alumni scrapbooks, Andre-Ross curated three exhibits for the Archives this spring, including one on the Archives’ extensive collection of religious postcards.

This February, Wheaton Archives and Special Collections digs into its collection of evangelical postcards, a now forgotten but vitally important resource for 20th century Christians in the United States.

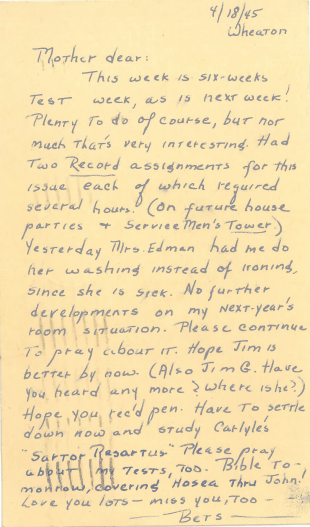

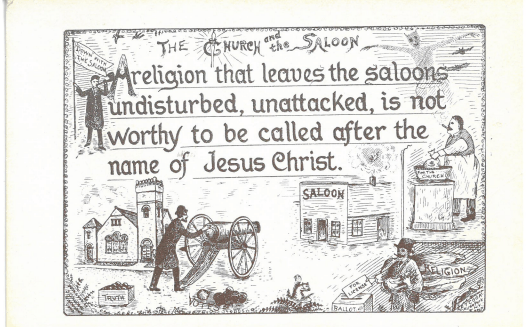

In 1873, the United States Postal Service introduced the “postal card”—a small and plain card that had its postage pre-printed on it, and cost just one cent, equivalent to about 25 cents today. It wasn’t big enough to send a full letter but was enough for a few sentences. Despite its simplicity, the postal card was a resounding success. For the first time in United States history, short form communication via cheap and accessible postal cards began to replace full-size letters.

An example of an unadorned postal card, sent from Elisabeth Elliot ’48 to her mother, circa 1945. From Elisabeth Elliot’s College Archives biographical file.

In the early twentieth century, the postal card would evolve into its more recognizable form as advances in printing technology allowed companies to cheaply mass produce cards decorated with images. This led to the second revolution in the postcard’s history: now, not only could it be used for short form communication, but it could also communicate ideas visually.

While our idea of the postcard generally involves a picture of some idyllic vacation getaway with the words “Wish you were here” written in flowery cursive lettering, during the twentieth century, the visual aspect of postcards was used to communicate religious, social, and political ideas to recipients. To this end, one of the demographics that seems to have made frequent use of postcards are Protestant evangelicals.

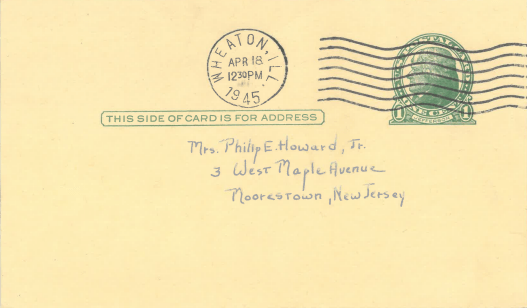

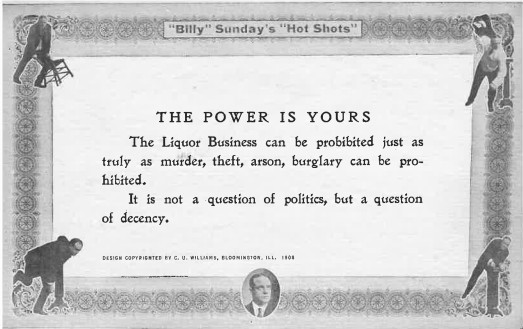

Evangelicals seem to have used postcards for a wide variety of purposes. In Wheaton’s archives, many postcards from the twentieth century are focused on the Prohibition movement, encouraging parents to vote against Prohibition to protect their children, exhorting recipients to uphold Christian values by voting for Prohibition, and featuring quotes from evangelists like Billy Sunday railing against the liquor industry. These demonstrate the political importance of the postcard for the political culture of twentieth-century America as a form of mass media before the invention and widespread use of technologies such as radio or television, as well as a source of quick communication.

A typical Prohibitionist postcard from the early 20th century. Undated, from CN 636, Binder 1.

A Prohibitionist postcard featuring a quote from Billy Sunday, a popular 20th century itinerant evangelist. Undated, from CN 636, Binder 7.

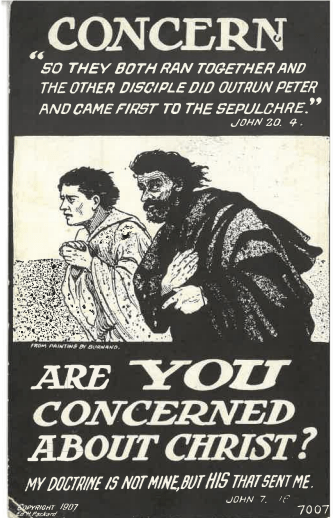

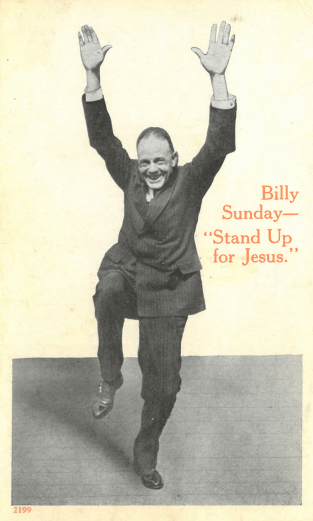

However, there are also many other postcards in the collection that are entirely apolitical. After Prohibition, evangelists, revivals, and evangelism are the second most popular subject matter of the visual half of the postcards in the collection. Billy Sunday makes a frequent appearance on many of the postcards, along with other minor evangelists. Pictures of revival meetings as well as locations of revivals are also popular. Others exhort Christians to take their faith more seriously, directly asking the reader, “are YOU concerned about Christ?”

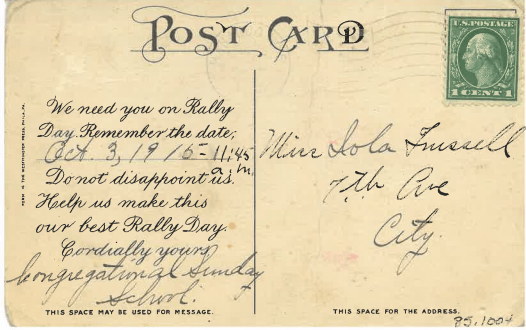

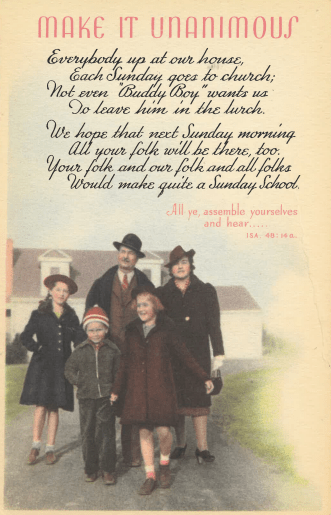

Beyond the Church’s outward facing aspects like politics or evangelism, a smaller group of postcards are interested with the more internal affairs of the church; Sunday School attendance, “Rally Days,” and opportunities for adults to attend educational meetings about their faith. This rather domestic focus, compared to the more wide-ranging messaging and possible appeal of the other postcards, suggests that twentieth-century Christians used postcards like these as a precursor to our modern texting or email—short form communication that could reliably reach its recipient in a short amount of time, and communicate a simple message or reminder.

An example of a Rally Day postcard from 1915. From CN 636, Binder 2.

A postcard emphasizing the importance of whole family attendance at church and Sunday school attendance. Undated, from CN 636, Binder 7.

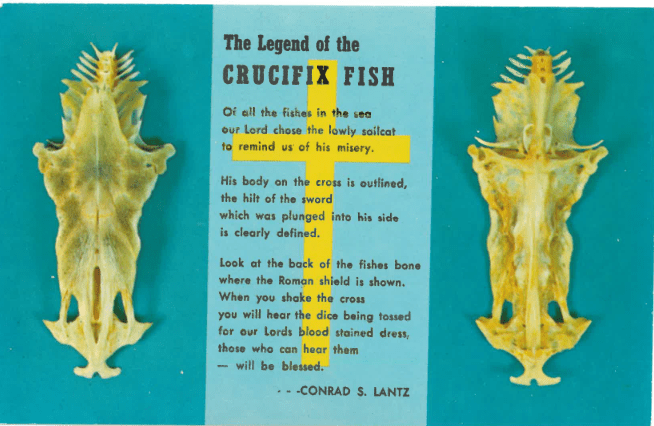

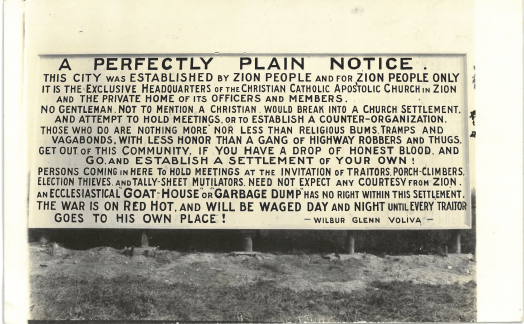

Finally, there are a number of rather bizarre entries in the collection that exist in a category of their own. While they certainly should not be viewed as representative of the whole of evangelical culture when they were produced, they do represent a very particular time and place that shaped their creation. To give an example of the type of postcard that fits in this category, we have the “crucifix fish,” and “A Perfectly Plain Notice:”

A postcard depicting the “crucifix fish.” Undated, from CN 636, Binder 6.

Postcard depicting a notice about the establishment of a community of the “Christian Catholic Apostolic Church in Zion” and its policy towards outsiders and non-believers. Undated, from CN 636, Binder 7.

All of these postcards are held in Collection 636: Religious Postcard Collection. Comprised of eight binders of hundreds of postcards from evangelical contexts across the United States, the postcards cover everything from politics to whether or not Christians should stop referring to God as “God” because of the word’s pagan Germanic origins. All told, they document a fascinating visual history of twentieth-century evangelicalism.

Other resources used:

- Prochaska, David, and Jordana Mendelson. 2010. Postcards. Penn State University Press.

- Pyne, Lydia. 2021. Postcards : The Rise and Fall of the World’s First Social Network. London, Uk: Reaktion Books.

Excellent, interesting exhibits! Strangely enough, the crucifix fish was still imprint in the 70s when I was a child in Florida.

LikeLike