In July 1974, 2,500 leaders from 150 countries gathered in Lausanne, Switzerland, for the International Congress on World Evangelization, better known as the Lausanne Congress. Over the course of ten days, evangelical leaders from around the world spoke in plenary sessions and workshops to consider the project of world evangelization in the modern era. An immediate outcome of the congress was the Lausanne Covenant, a statement of Christian belief and lifestyle that became a touchstone for many evangelicals around the globe.

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Lausanne Movement’s founding Congress, Wheaton Archives & Special Collections features highlights from Collection 46: Records of the Lausanne Movement, as well as our oral history collections with Lausanne leaders and participants.

Planning the Congress

In 1966, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association and Christianity Today hosted “A World Congress on Evangelism” in Berlin. Although a seminal conference in modern global evangelism, Christian leaders, like Billy Graham, John Stott, Leighton Ford, A. J. Dain, and Donald Hoke, among others, began to correspond about the possibility of holding another Congress focused on, as Graham wrote to A. J. Dain, “press[ing] for the evangelization of the world in our generation.” (Collection 46, Folder 1-1).

A 1990 oral history interview from Wade Coggins, missionary and staff member for Evangelical Fellowship of Mission Agencies (EFMA), records his memories of the genesis of the Lausanne Congress’s program on “world evangelization”:

COGGINS: In other words [in Berlin ’66], they were thinking of local churches everywhere – but thinking of what the local church would do to reach its people, within its families, get nominal Christians. How to reach out beyond its existing congregation to get new members. It had to do with evangelism in the sense of the local church, wherever that local church was located. Now it began…it touched a little, of course, when you start talking about local churches in Africa or Asia obviously, you’re now beginning to look at a world kind of thing. So then when they move from Berlin ‘66 to the concept of the Lausanne at ‘73 [1974] that’s where I remember sitting with Harold Lindsell and Clyde Taylor. And they were wrestling with the idea, “Now how do you begin to look at this more including the mission aspect, not just evangelism as it’s done by individuals in the local church but how do you bring into that discussion the whole idea of getting from one culture to another to get a church started.” And so quite a bit of material was brought to the Lausanne conference. And I think the name was switched at that point from “Evangelism” to “Evangelization” so that it began to deliberately look at the whole concept of world evangelization but in Berlin it was quite narrowly focused in the idea of the church reaching out.

Oral History Interview with Wade Coggins, Collection 414, T9

In November 1971, Billy Graham convened a meeting in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia to discuss the possibility of a congress for a coordinated world-wide evangelistic movement, devoted to strategic planning, inspiration, and fellowship for evangelism. A Planning Committee was established, led by A. J. Dain, a prominent Australian evangelical Anglican bishop, with funding for the Congress coming from the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA) and other private donations.

Several folders in Collection 46 document the origins of the Lausanne Congress and the work of the Planning Committee, including the agenda and minutes from the 1971 meeting (held in Folder 1-1). The early correspondence between committee members also reveals the foundational concerns animating the Congress, including questions of theology and culture, the relationship of missions and the church, methods for evangelism, and new developments in global ecumenicism and evangelical social concern. One example among many in the collection is the below 1972 letter from Carl F. H. Henry to Jack Dain.

Reflecting the central focus on world evangelization, the Planning and Programming Committees sought to create a practical and globally oriented Congress – with plenary addresses from evangelists and theologians across traditions and cultures and small group sessions focused on national strategies and concrete tools for evangelism. Plans were made to provide simultaneous translation in seven languages, and both the Programming and Participant Committees sought involvement from across the evangelical world, with half the participants and speakers coming from non-Western countries. Read a report from Folder 1-22 on the development of the Lausanne 1974 program from Leighton Ford, Chairman of the Program Advisory Committee.

Together in Fellowship

After three years of planning, the more than two thousand participants arrived for the first day of the Lausanne Congress on July 16, 1974. In addition to the major plenary addresses, the program consisted of Bible studies, prayer cells, workshops on evangelistic methods and strategies, small group discussions, reports on various theological topics and the global church, as well as an evangelistic rally from Billy Graham. Two of the Congress’ defining moments were addresses by Ralph Winter, American missiologist and founder of the U.S. Center for World Mission, and C. René Padilla, an influential Ecuadorian theologian. In the first address, Winter stressed the importance of evangelism to “unreached people groups,” while Padilla challenged Christian leaders to envision social justice efforts as integral to global evangelism.

One Congress participant, Arthur Glasser, Dean of the School of World Mission at Fuller, reflected on his impressions of Lausanne in 1995 oral history interview.

GLASSER: Billy Graham was willing to draw in people. They would make the series [?] of confession, “I believe in Jesus,” you know, that’s enough. Th…forget about the groups with which you were associated, you know, that sort of spilling over so that ….and it was there that Billy got a vision. I remember one of our faculty members saying, “You know what Billy Graham has done? It’s not the number of people he has led to Christ. It’s the fact that he got Evangelicals to work together.” And that’s what Lausanne 1974 was. When they brought people together. I met my first large groups of charismatics of various sorts. There were people from some of the Orthodox groups, you know, all this. Quite a…and that was a great thing. His money made that possible. Now, mind you , it so happened I was the Dean here at the time and we got some big gifts. They just came through. It was very wonderful. So that our faculty as a faculty was able to attend, and we had, oh, about sixty or seventy School of World Mission people at…at Lausanne. And…and when he got there and you started to break out and the people, boy, it was exciting.

SHUSTER: So that would…that’s what you would say would be the greatest significance of those two congresses…. Berlin and Lausanne was that they brought the Evangelicals together.

GLASSER: The Lausanne Declaration that came out of that. Where at long last Evangelicals of all shades and colors and associations could say, “This is what we believe.”

Oral History Interview with Arthur Glasser, Collection 421, T8

Wade Coggins’ interview from Collection 414 also records his experience at Lausanne:

SHUSTER: What memories do you have of the meeting?

COGGINS: There are various kinds of memories. They…some…in some ways highlights our…times that I’ve found believers from different places at a meal time and asked them about how things were in their country. I remember once talking to a man from Turkey, a place where Christianity is highly restricted. And he was such a radiant Christian and we talked for a while and I said, “How do you get together, what do Christians do to get acquainted with each other?” “Oh,” he said, “we have some interesting ways.” He said “We’ll…in the summertime we’ll decide on a day at the beach and we’ll pass the word around to people where we’re going to be, so people…a lot of Christians would come, and they would come and spend the day together at the beach.” And they sit around as any set of people would at the beach. They don’t do any public meetings, but this gave them…gives them some time to sit on the sand and talk to each other and encourage each other just in the normal flow of things. And they talked about…weddings and birthdays and whatever family celebrations. They turned those into opportunities to invite their friends and their friends come and they are able to fellowship as Christians under the theme of whatever the festive occasion is. So, I thought…that’s something that stuck with in my mind as an interesting response to a tough situation. They found ways to work around it.

The public meetings…there were outstanding speakers and the papers were excellent and those are still great resource papers to go back and pick up on those. There was the public rally, an evangelistic crusade which was held on a Sunday in the middle of the conference at a stadium there in Lausanne, attended by hundreds of people. In fact, the stadium was about full, and Billy Graham preached an evangelistic message and the local churches were involved in that. And the pastors and their people were counselors and they had regular, typical evangelistic appeal and response. There were a number of responses. I don’t remember the size of the crowd but there was a public response to evangelism that they…. And that was an outstanding experience.

Small groups were interesting. And I met some with the Chinese group [Chinese Congress for World Evangelization]. I had had some contact with some of the leaders in the [United] States and they were…they added to that by pulling in some from other parts of the world. Of course, at that time the mainland [China] was considered closed and they didn’t know much about what was going on there. But the ones around the Pacific Rim who were Christians had some pretty strong churches and they had a good group out of the whole Lausanne movement. And they met together regularly, and I was informed actually a Chinese movement which is still active today which has had its own large congresses in the meantime and has stimulated a lot of missionary interest by Chinese who are now starting to send missionaries.

Oral History Interview with Wade Coggins, Collection 414, T9

The Lausanne Covenant

Perhaps the most important result of the Congress was the creation of the Lausanne Covenant. This was a statement of the Christian Gospel and its proclamation in the contemporary world. Many integral topics were covered, including the social responsibility of the Christian, the place of the church, and the relationship of evangelism to culture.

Development of the Covenant began well in advance of the Congress. An initial draft made up of key statements from the plenary papers was sent to participants in April 1974. These responses were incorporated into a second draft which was then reviewed by the Drafting Committee, including John Stott, Hudson Armerding, and Samuel Escobar. On the third day of the Congress, the Covenant was submitted to participants for comments and on July 24th a final version was distributed in all the languages of the Congress.

Rather than a creed or treaty to be signed in mass by representatives of churches and institutions, the Covenant was intended to be signed by individuals to indicate their agreement with and commitment to the vision of evangelism it proclaimed. Some 2,300 attendees of the Congress signed it, including Billy Graham.

Reflecting on the development and impact of the Covenant, Robert Coleman, professor of Evangelism at Asbury Theological Seminary and future member of the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelism, summarized:

SHUSTER: For you personally, what stands out as most significant in the conference?

COLEMAN: The most significant outcome of Lausanne was the Covenant, I felt. The Lausanne Covenant still to this day is probably the best representative statement of where the evangelical comes down, not just on evangelism but on other issues: the inspiration of Scripture, on…on social compassion, on many other areas of…of concern. But it gave a very clear forthright statement of the essential meaning of the Gospel. That was a rather small committee that formulated that…that statement, probably half a dozen people. John Stott was I think probably the most formative voice in that. J.D. Douglas I think was involved. There were…there were other things that came out of Lausanne. I think it was…it gave momentum now to the evangelical movement and a much wider scale than had happened in Berlin. Berlin really gave birth to what followed in Lausanne. But Lausanne now opened up a wider area of…of concern and it also drew in much larger participation.

Oral History Interview with Robert Coleman, Collection 563, Tape 7

While the Drafting Committee sought to develop the Covenant as a collaborative process, the final text was not without criticism. René Padilla, plenary speaker and Latin American theologian, gave voice to many of the Third World participants in the Congress who charged that the Covenant did not go far enough in its description of the relationship of evangelism to social justice and responsibility. René Padilla described his response to the Covenant in a 1987 oral history interview with the Archives:

ERICKSEN: [Pauses] How did…I don’t know exactly what it was called, but the response to the [Lausanne] Covenant develop? The alternative covenant or whatever it….

PADILLA: “A Call to Radical Discipleship,” it was called…. Well, there was quite a number of people at the Lausanne Congress who felt that the Lausanne Covenant did not go far enough, that when it came to relating the gospel to social issues, it was still trying to negotiate with people who felt that, “Well, the main task of the church is preaching the gospel.” That congress was attended by quite a number of people who had already been thinking along the same lines that we had been thinking in Latin America. Some of them from the US, very few, but among them, John Howard Yoder, [Ron] Sider. Then there were people from England, who had become very socially aware, a few from Australia, and then a lot of people from the Third World. I can’t remember the exact day, but it was a day when we were free to do whatever we wanted to, sort of a rest. I think it was a Sunday afternoon. People wanted to go to Geneva or Lucerne or somewhere to do a bit of tourism, but three or four of us invited people to come to a meeting to discuss these issues of social justice and so on, and we were amazed at the response. We had a meeting with about five, six hundred people, even though it was improvised and called at the last minute. So that…that is where the response to Lausanne was thought of, and there a l…a small committee appointed there to write down what had come out of the discussion.

ERICKSEN: Once the response had been written, what…what happened then?

PADILLA: There was a backlash immediately. People who reacted, as I say, even at the Congress itself. I felt the hostility of many Americans. Very much so. And afterwards, of course, many people were very critical of what we had said, and of the radical discipleship group, and of John Stott, who had given us his support, publicly. He had said, “I agree with the response to Lausanne, and I have signed the response.” I feel that out of Lausanne came a serious reflection which is represented by a number of…of meetings, which were held afterwards.

Oral History Interview with René Padilla, Collection 361, Tape 1

Conversations on the relationship of social justice and evangelism continued through subsequent congresses and formed a major part of the later Manila Manifesto. Since 1974, the Lausanne Covenant has been accepted by many Evangelicals around the world as the best contemporary definition of the Great Commission and has been used by many international Christian groups as their statement of faith.

Forward from Lausanne

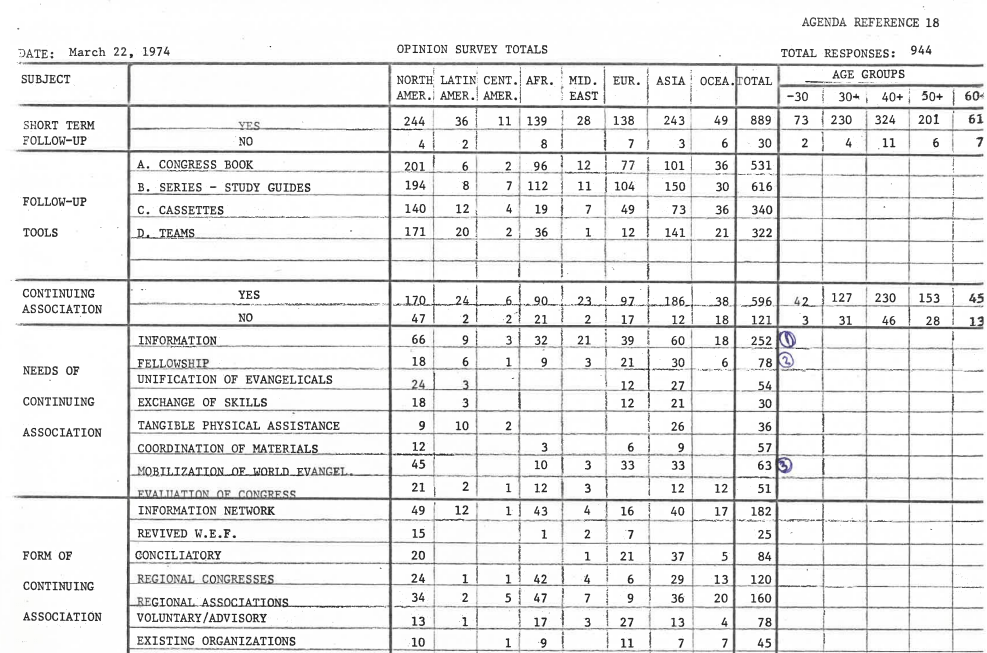

Contributing to the long-term impact of the Lausanne Congress in 1974 were the consultations held in 1973 on how best to continue the Congress’s goals after the meeting, including an extensive survey of the attendees of the congress to evaluate if a continuing organization was desired and if so, what shape and mission it should take. From these meetings came the first plans for the Lausanne Continuation Committee (LCC).

The process of selecting members to constitute the LCC began at the Congress, resulting in the selection of forty-eight people to plan for future consultations and congresses as needed; this number was later expanded to seventy-five. First meeting in Mexico City in January 1975, the Continuation Committee concluded that “an international network for world evangelization be developed as the ongoing expression of Lausanne.” Read the 1975 statement Forward from Lausanne, held in Folder 21-2, Collection 46: Records of the Lausanne Movement.

This network was officially established as the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization (LCWE) in 1976. At its inception, Leighton Ford was chosen as LCWE’s Chairman and Gottfried Osei Mensah was designated its Executive Secretary.

In 1989, Lausanne II was held in the Philippines and in 2010 a third Congress was held in Cape Town, South Africa. The latest meeting of the Lausanne Movement is this year’s Seoul-Incheon 2024 Congress in September.

Wheaton Archives & Special Collections holds thousands of pages of correspondence, reports, planning documents, and plenary papers, as well as audio recordings and other records on the Lausanne Movement. Explore the finding aid for Collection 46: Records of the Lausanne Movement, or review the many related collections on our archival database.

Pingback: Billy Graham – February 21 - The Transhistorical Body