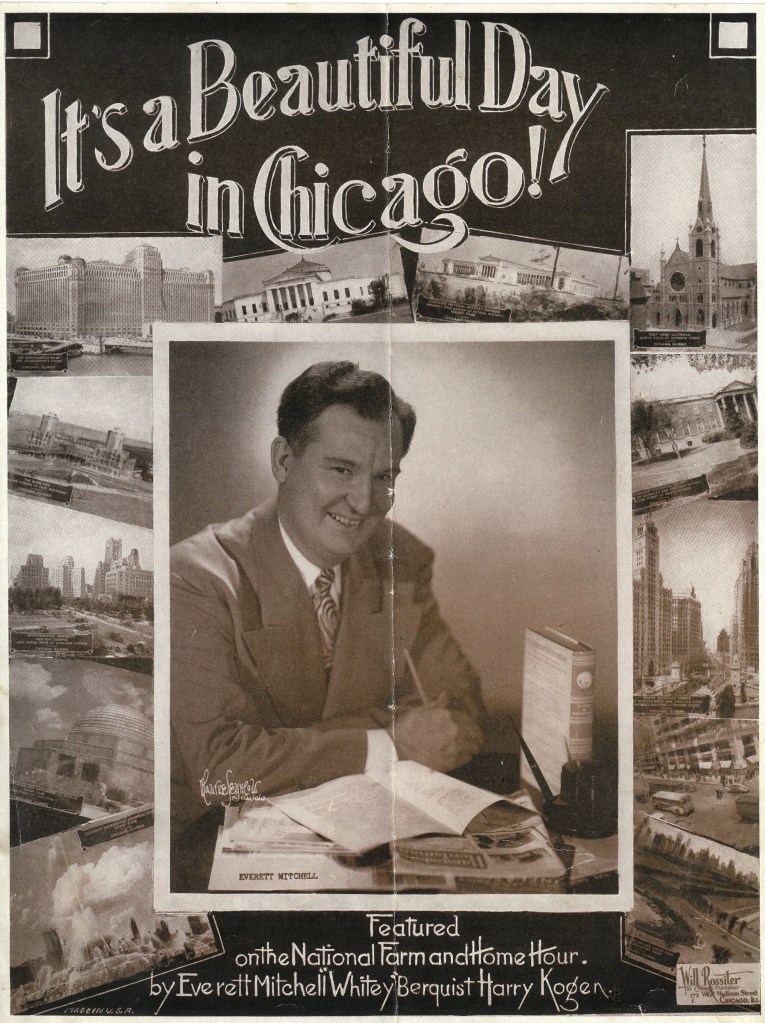

Along with hundreds of collections on global missions and evangelism, Wheaton Archives & Special Collections also holds records documenting the history of Chicagoland, from institutions like the historic Moody Church, Chicago Gospel Tabernacle and the Chicago Sunday Evening Club to individuals like William Leslie, Herbert J. Taylor, Vaughn Shoemaker, and Harold “Red” Grange. This month, Wheaton Archives & Special Collections features one such collection, the papers of hymn singer and radio broadcaster Everett Mitchell, best known for his memorable opening line, “It’s a beautiful day in Chicago!”

Everett Mitchell was born on March 15, 1898, just eight months after the radio was invented by Guglielmo Marconi in 1897. His father, George Mitchell, was a fireman for the Chicago North Western Railway, and the family lived on a small farm on the Moreland Prairie, now part of the Austin neighborhood on the west side of Chicago.

Of Quaker lineage, Mitchell learned dozens of hymns at an early age and often sang as he performed his chores. Soon his melodious voice attracted the attention of local churches seeking musicians and revivalists. One of the nation’s prominent evangelists, Gypsy Smith, noticed young Everett and hired him as a soloist for Smith’s revival services at Pacific Garden Mission in downtown Chicago. Smith later convinced Billy Sunday to utilize Mitchell’s talent for summer revival services at Winona Lake, IN. There he sang hymns during Sunday’s invitation plea, imploring hundreds of seekers to accept Christ as savior.

In a 1989 oral history interview with Archives & Special Collections, Mitchell described his experience meeting and singing for Billy Sunday:

Now, when I sang for him for an audition, it was unaccompanied, and I sang for him…”I Shall See Him Face to Face.” And I never have seen anybody that reacted like he did, because when I finished, he had tears in his eyes. Now, I had a very peculiar born-in trait, and that was what…. There was kind of a little wail in the…in the…in the voice, that appealed to people. In the summertime, he had some services there at Winona Lake, Indiana, so he asked me if I would sing at some of those services, and especially sing the invitation song. And his favorite was “Softly and Tenderly Jesus is Calling, Calling to You and to Me.” …. “Come home, come home, come home, Ye who are weary come home.”

Interview with Everett Mitchell, Collection 140, Tape 1

After completing high school, Mitchell initially went into business, working as a clerk at First Trust and Savings Bank. However, a friend’s dare led him to an entirely different career. Below, Mitchell describes his unlikely entry into radio broadcasting:

Ah. Yes. I was…I started in radio in 1923, of November. There was only at that time one or two stations in Chicago, and one of them was KYW. I got into radio on a dare, because I had been doing some appearances at the local churches and giving some concerts, and some of my young friends, who had been listening to radio on a crystal set thought that it…it would be a good idea for me to go down and have an audition. Well, in those days, usually a piano player was the only one that was on duty, and the only talent he had was whoever happened in the door. So I went down, and…and sang on old KYW, and I remember the song that I sang which was “The Sunshine of Your Smile.” And so they accepted me, and then I began to sing on the various radio stations, as they came into being. And in 1924, I went to WENR, which was E.N. Rollins’ station of all-American radio. And there, I sang on a Christmas Eve. They didn’t have any talent, so I didn’t have any trouble getting into that one, and I sang the “Prisoner’s Song.”

And this owner of the station Mr. E.N. Rollins, was listening so he called, and asked me if I wouldn’t want to sing permanently on the…on the staff. I did sing permanently on the staff, and then within six months, I was managing the station. So that started my radio career, which lasted forty-four years.

Interview with Everett Mitchell, Collection 140, Tape 1

Mitchell received no payment for his first 18 months as a radio singer. He continued working at the bank until the bank supervisor, noticing Mitchell’s often bedraggled appearance after his late-night radio gigs, presented him with an ultimatum: leave radio or be fired. Mitchell quit with little deliberation. As he departed, his supervisor fumed: “Radio is nothing but a passing fad!”

Mitchell entered a full-time position at WENR where he soon developed a consistent programming format, allowing a convenient predictability for both the performer and the listener. Now he could schedule jazz, gospel, or classical music programs ahead of time, capturing a more diverse audience. Mitchell also introduced service and educational programs, as well as sought out commercial advertising options, producing the first sponsored show on the Chicago airways.

After WENR was purchased by NBC in the late 1920s, Mitchell assumed responsibilities as announcer for the popular “National Farm and Home Hour,” a program dedicated to presenting livestock and agricultural reports, as well as light entertainment, for the nations’ nine million farmers and farmworkers. Mitchell reported that he got the job because he was the only person of the 26 applicants who could describe the difference between a strawstack and a haystack.

Soon after Mitchell joined NBC, the Great Depression devastated the country, hurling thousands of Americans into financial ruin. On May 14th, 1932, riding the train to work, Mitchell wondered how to combat the increasingly dark national mood. In an oral history interview with biographer Richard Crabb, Mitchell recalled that “It was raining and misting. It was in the depths of the Depression,” and “a fellow on the train was complaining about the weather and hard times. He said, ‘As far as this nation is concerned, we’re doomed. God has forsaken us.’ And I said, ‘No, we’ve forsaken God to worship the almighty dollar.'” That morning, Mitchell, not discussing his intent with the station management, stepped to the microphone to introduce the show, stating confidently: “It’s a beautiful day in Chicago! It’s a great day to be alive, and I hope it’s even more beautiful wherever you are.”

The impromptu greeting upset the station management, but created a sensation among an audience desperately hungry for good cheer. When the phrase was briefly discontinued, the station received 13,000 calls and letters asking Mitchell to bring it back, and as a result, the opening line became his signature for the remainder of his career. The greeting even received a special presidential dispensation from the World War II prohibition against reporting weather conditions over the radio.

The program and Mitchell’s new role as host was hugely popular – both in agricultural areas, as well as with urban and suburban audiences. Explaining the wide appeal of the show, columnist Jack Thompson wrote in Radio Parade (1936), “For although the program is the farmer’s equivalent to the businessman’s ticker tape…it will also tell you the newest method of roasting a turkey and how to get a government loan or make your garden grow, interspersing this with the music of Walter Blaufuss and the orchestra, the singing of a soloist or vocal team, and the information comment of the Master of Ceremonies Everett Mitchell.”

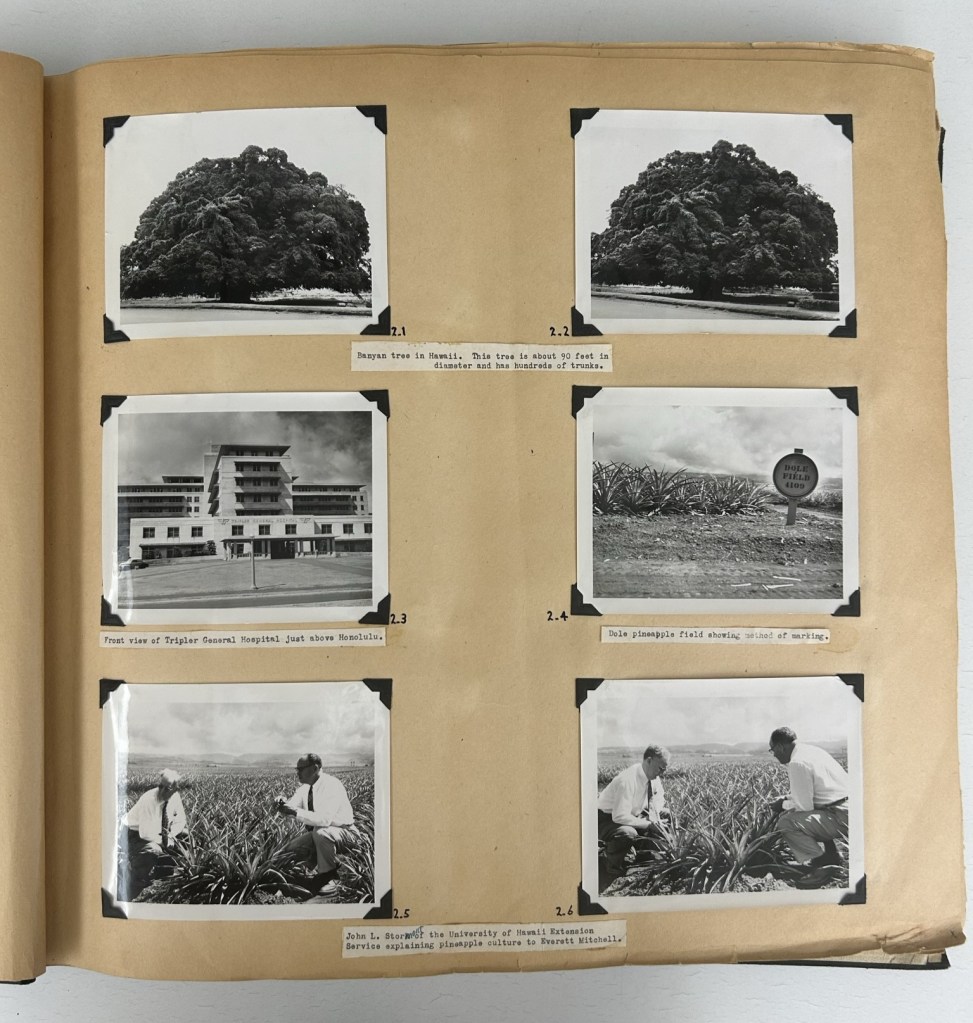

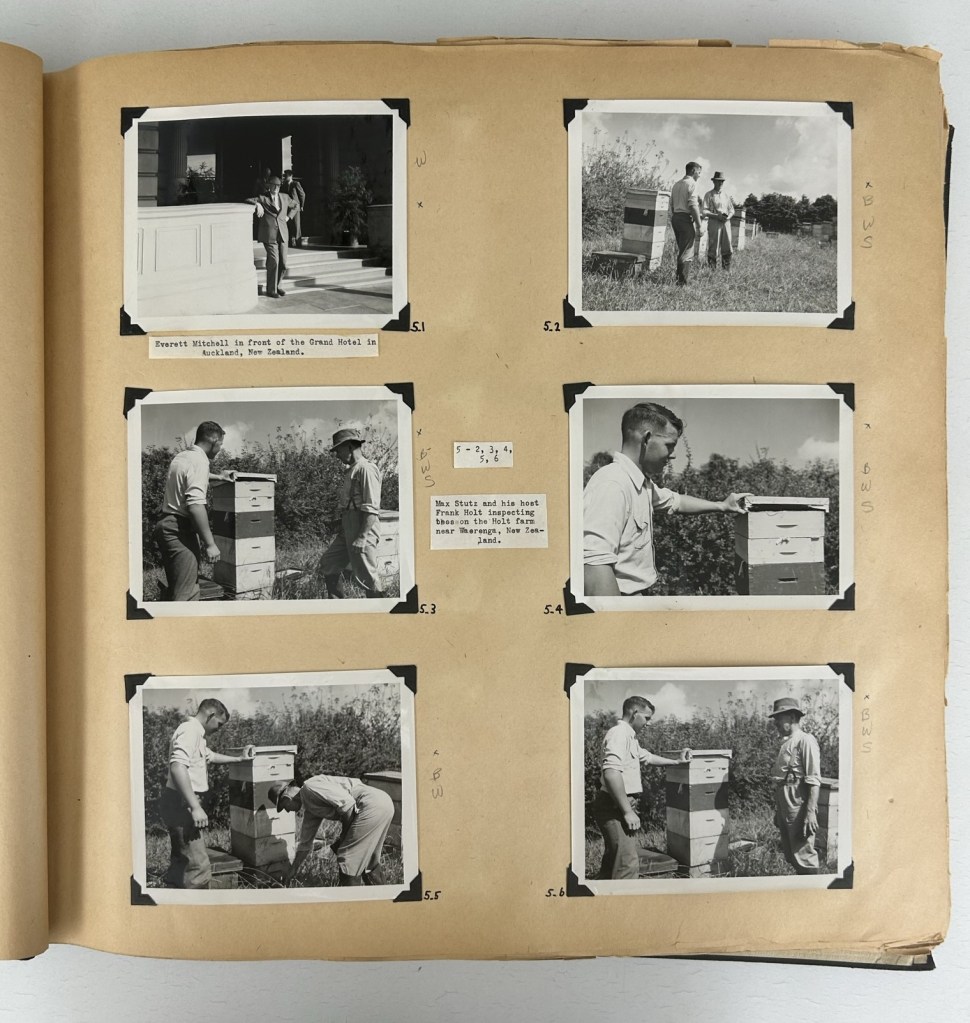

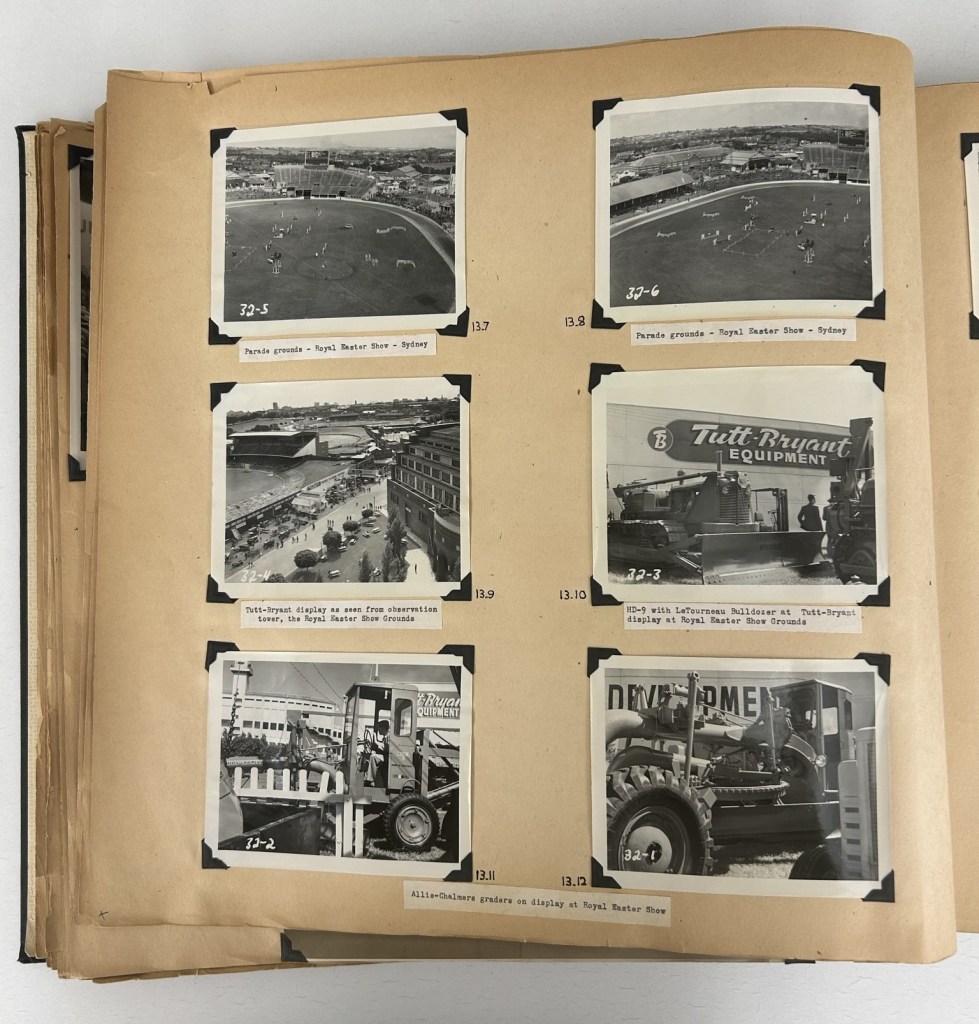

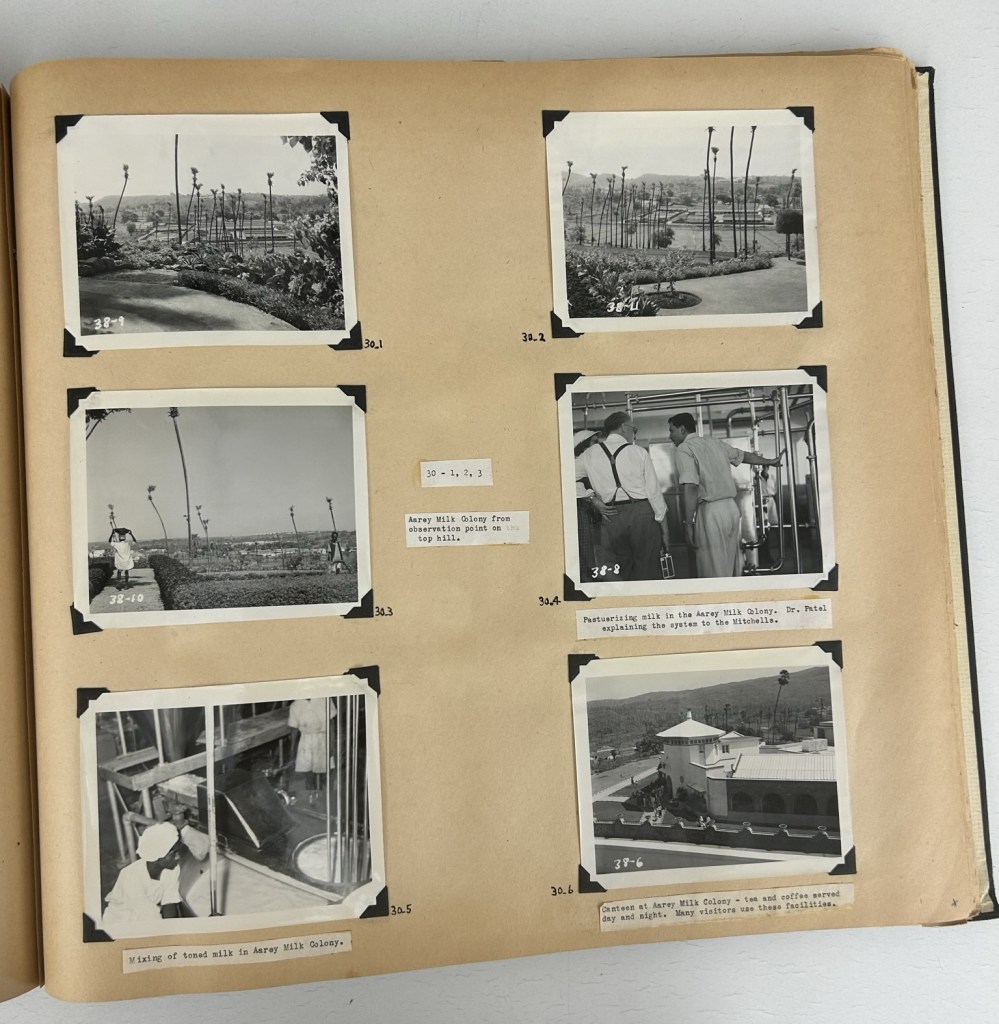

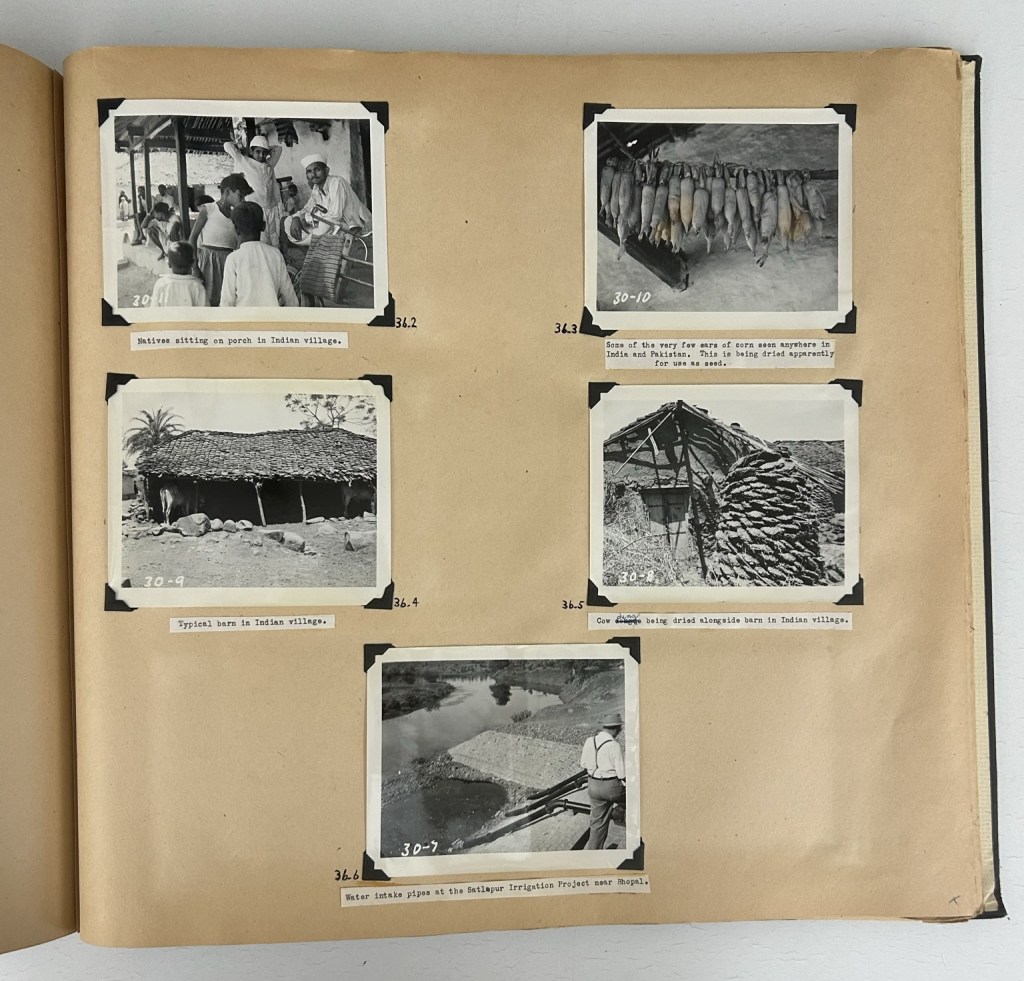

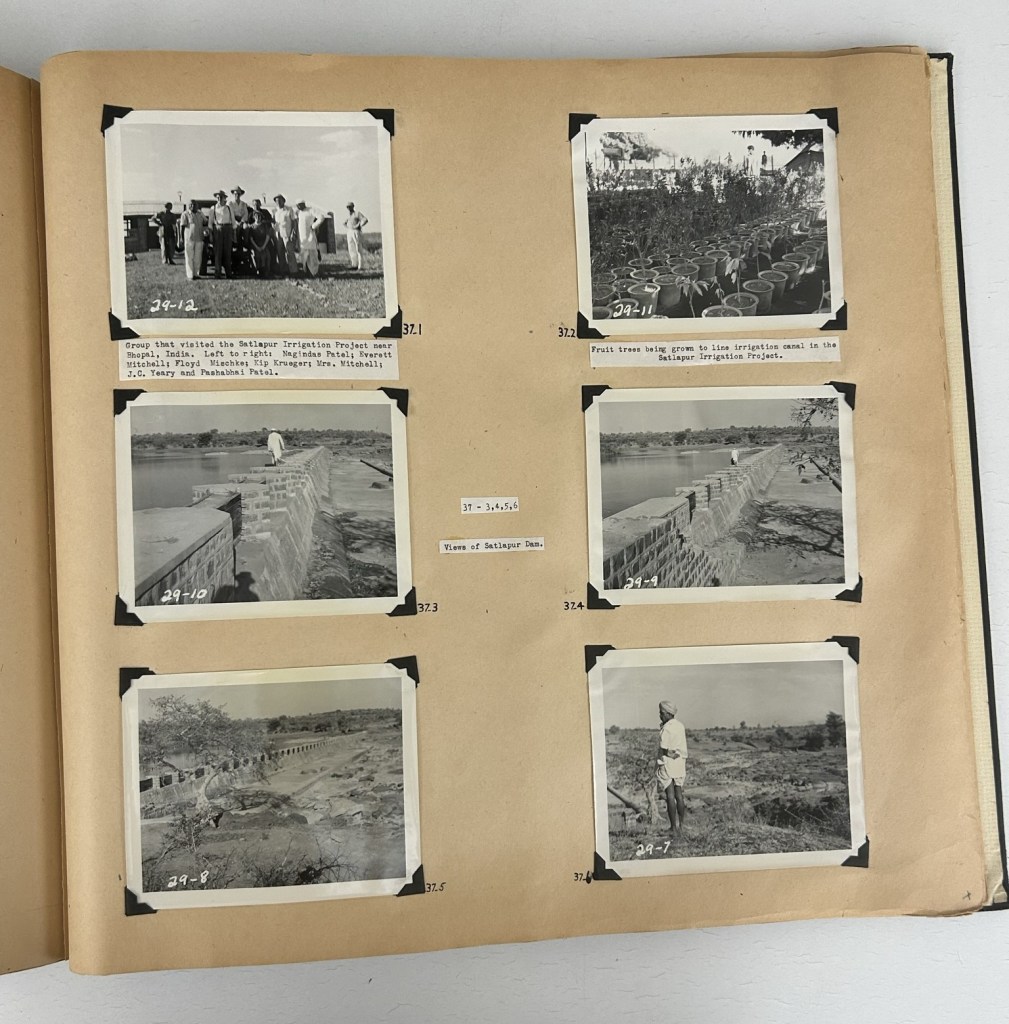

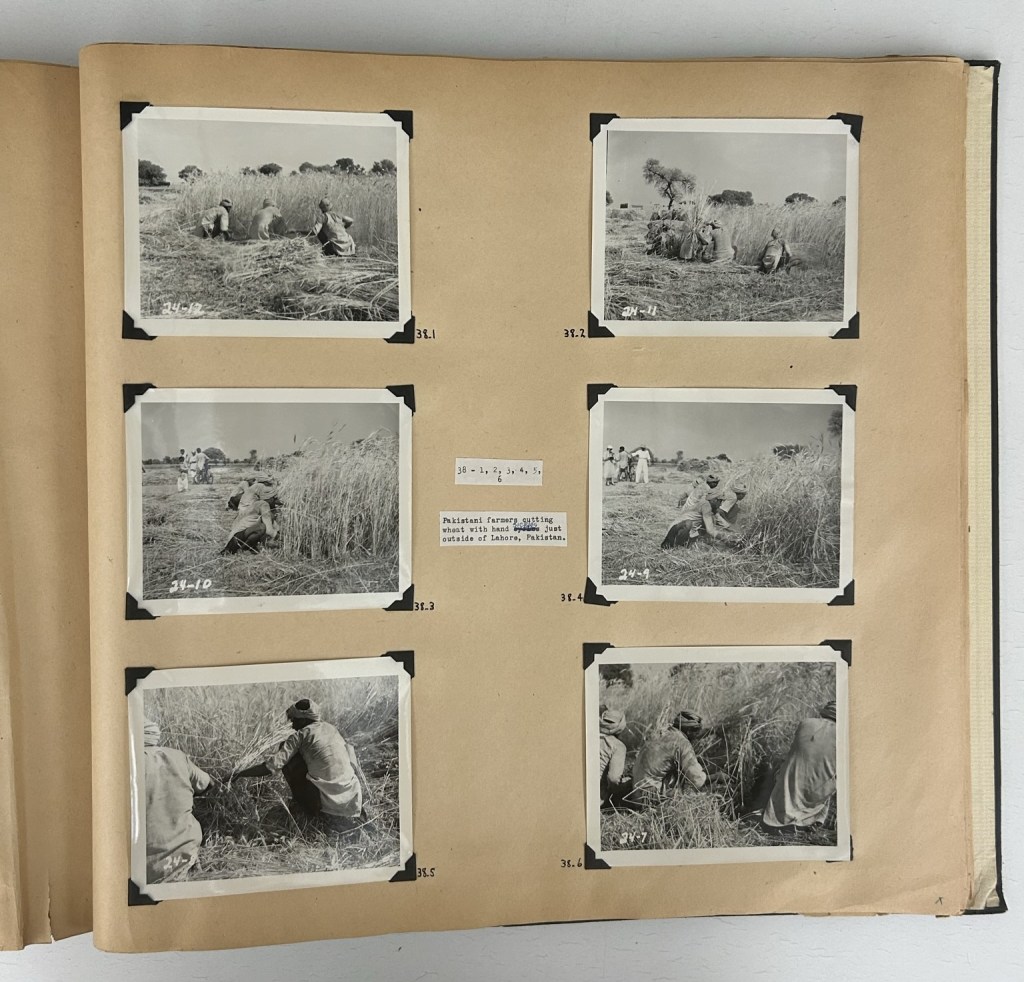

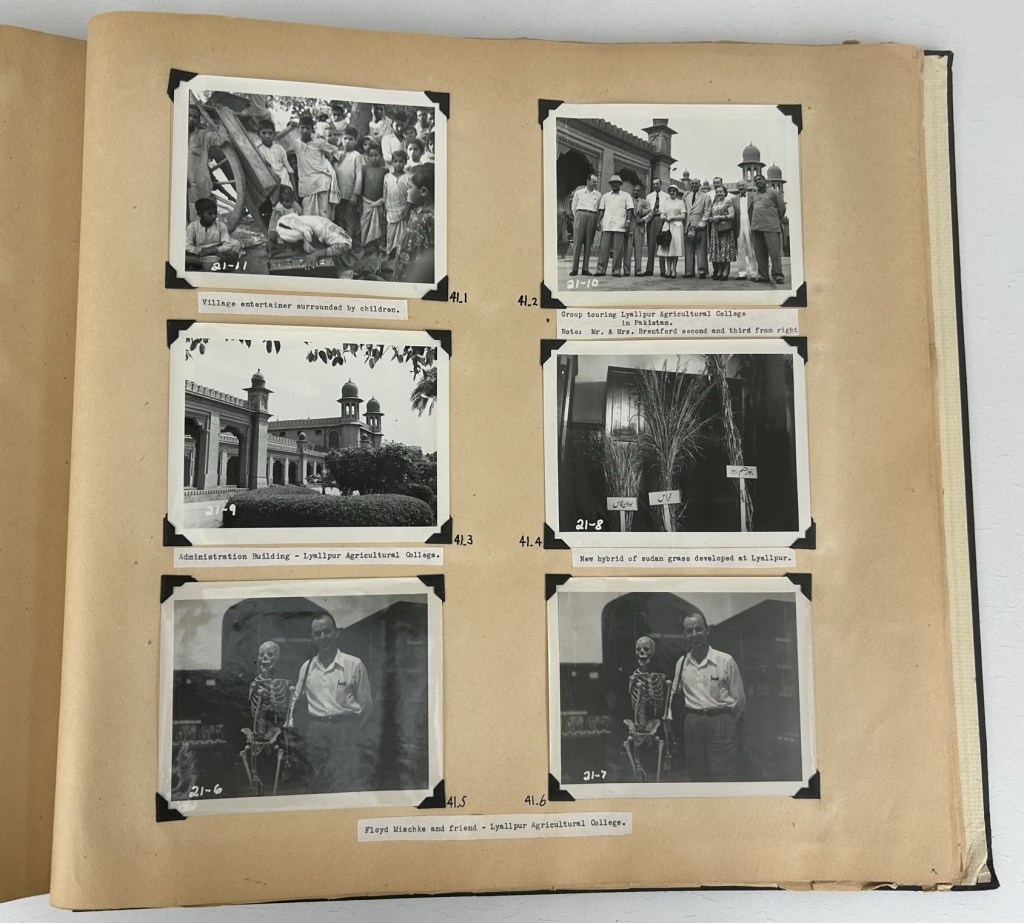

An extensive traveler, Mitchell broadcast half of his shows from farm locations. He traveled over 2 million miles and visited over 50 countries, reporting on agriculture in Europe, Central and South America, Russia and Asia. At the invitation of the U.S. Department of Defense, he also served briefly as a war correspondent in Korea, investigating famine during the Korean War. Mitchell’s two travel scrapbooks held in SC-14: Papers of Everett Mitchell provide a fascinating snapshot of mid-century agriculture practices and projects across the world, from pineapple production in Hawaii to irrigation in India.

Pages from a scrapbook documenting the 1953 world travels of Everett Mitchell, on his “Around the World Good Will Tour,” accompanied by International Farm Youth Exchange (IFYE) students and sponsored by the tractor and farm manufacture Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Co. SC-14, Box 16.

The 1950s saw a gradual decline in the audience for the National Farm and Home Hour, spurred by changes in NBC’s broadcasting structure and the exploding American interest in television. Following several timing and programming reductions through the 1940s and 1950s, the National Farm and Home Hour quietly disappeared from the air in 1958. After 40 years of broadcasting, hosting several national and regional programs, and a 10-year stint as NBC’s chief radio announcer for its Midwest divisions, Mitchell retired in 1967. He died November 12th, 1990, in Wheaton, Illinois where he and his wife lived on Beautiful Day Farm.

Everett Mitchell’s story (and that of early radio) is further detailed in Richard Crabb’s biography, Radio’s Beautiful Day (1986). Additional photographs, clippings, correspondence, and audio recordings documenting the life of Everett Mitchell, as well as the development of radio in Chicago and the National Farm and Home Hour, are open for research at Wheaton Archives & Special Collections. Review the finding aid for the collection at SC-14: Papers of Everett Mitchell.