Last September, Wheaton Archives & Special Collections hosted Dr. Devin Manzullo-Thomas for the annual Archival Research Lecture, where he presented “Exhibiting Evangelicalism: Exploring the History of Christian Museums in the United States.” This month, we feature an interview with Dr. Manzullo-Thomas, delving into his archival exploration of how evangelical communities engage with and commemorate their histories.

When and how were you first introduced to Archives & Special Collections?

I first visited the Archives and Special Collections at Wheaton in 2013 or 2014, to conduct research related to my denomination, the Brethren in Christ Church. (Several Brethren in Christ leaders are either alumni of Wheaton College or are otherwise represented in Archives & Special Collections materials.) While there, I also visited the Billy Graham Museum on the first floor of Billy Graham Hall, and my interest was piqued. Because of my training as an archivist/public historian and my scholarly work on the history of my own denomination, I’ve long been interested in how religious communities present their history in museums and historic sites. I started wondering: “How have other evangelical groups and institutions represented the past in public spaces?”

Eventually, I turned this question into the basis for my doctoral dissertation at Temple University, and Wheaton’s Billy Graham Museum became one of the case studies I examined in my research. That research eventually culminated in my first book, Exhibiting Evangelicalism: Commemoration and Religion’s Presence of the Past (2022).

What kinds of collections have you used most heavily and how were they applicable to your topic?

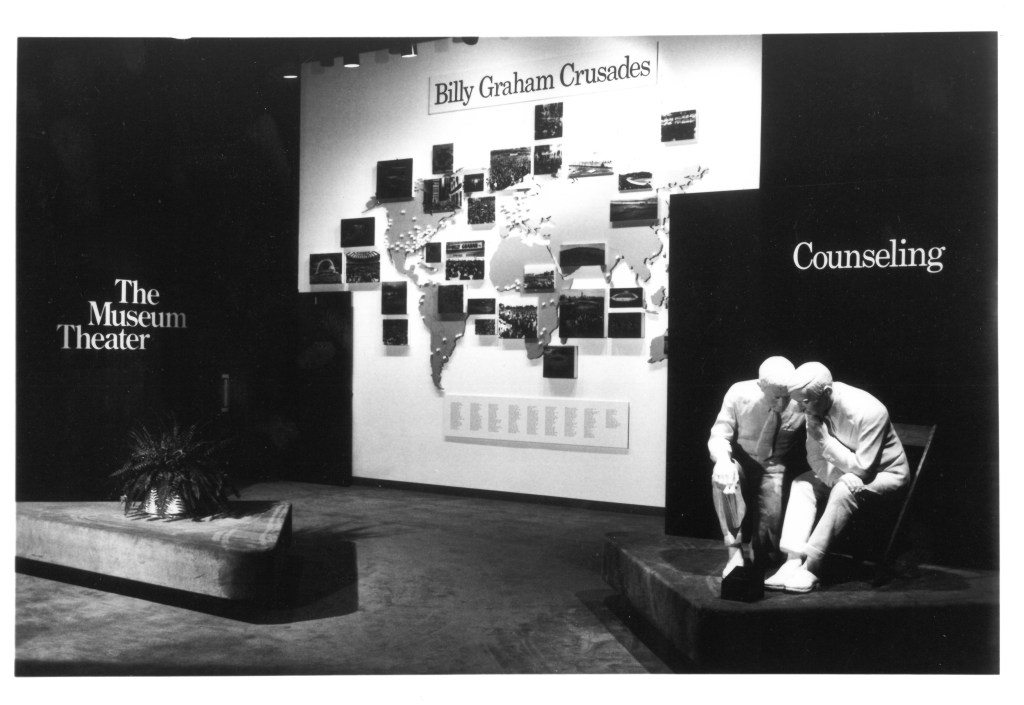

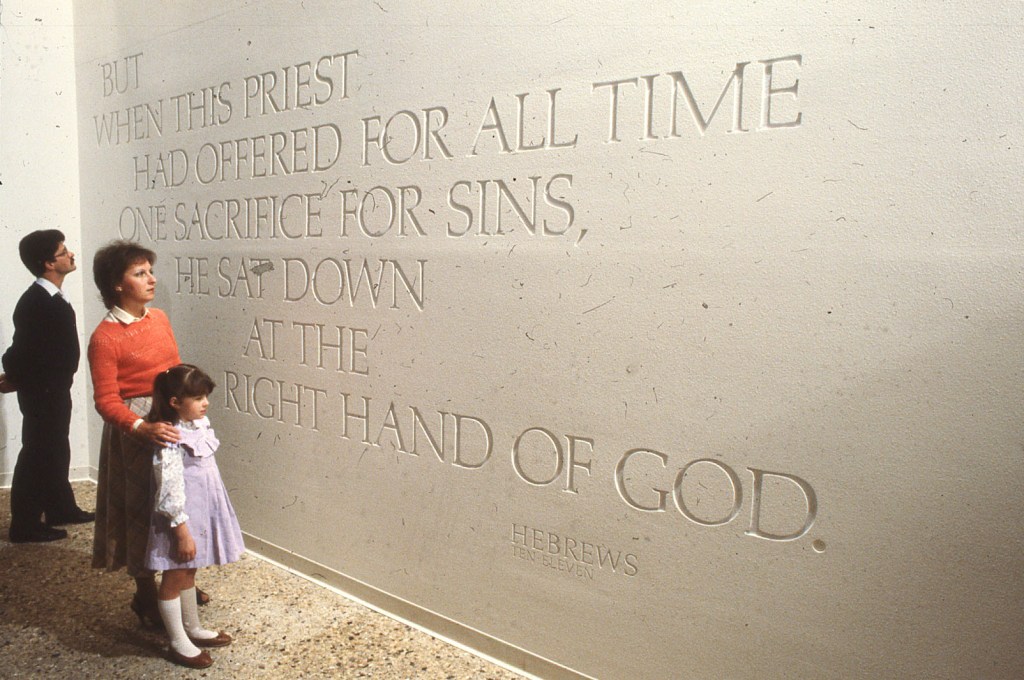

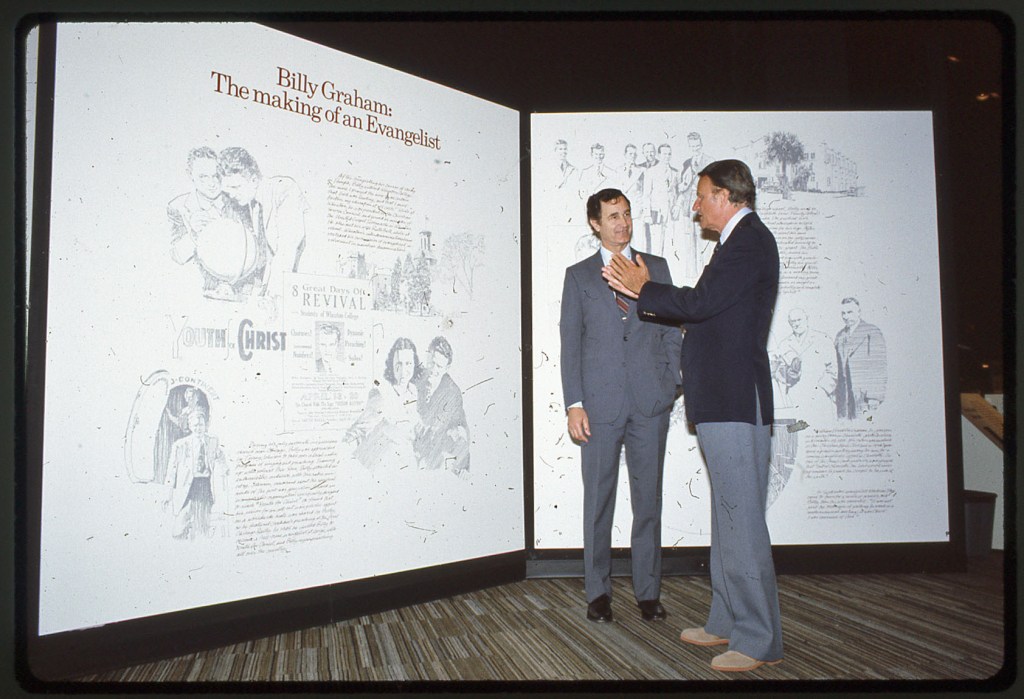

When conducting research for Exhibiting Evangelicalism, I spent hours poring over materials from Collection 003: Wheaton College Billy Graham Center Records. The collection has extensive records document the planning, development, and day-to-day administration of the Billy Graham Museum, which helped me to understand how curators and other staff members thought about the purposes of the Museum from its earliest years and into the present. The collection also has significant records related to the particular exhibits in the Museum, which were really helpful in understanding their development, and material on visitor experience at the Museum.

Many of these records were the typical sources used by historians writing institutional histories: correspondence, reports, memoranda, and the like. But my methods as a historian tend toward the interdisciplinary, so I was thrilled to get my hands on non-textual sources in this collection: audio recordings from interactive exhibits at the Museum; photographs of the original Museum in the 1980s as well as the renovated space in the 1990s and 2000s; diagrams and blueprints of various iterations of the Museum; and more.

I also benefitted from the interest of Archives staff, especially Katherine Graber, Bob Shuster, and Paul Ericksen. Over various research trips, I shared my project and some of my findings with the staff. As they learned more about what I was interested in, they made available to me various accessions within Collection 003 that had not yet been fully processed; I had the privilege of examining records that previous researchers had not had access to. These records significantly deepened my understanding of the Museum, both during its development and its years of operation; without them, I would not have been able to write my book.

There’s a lesson here for researchers: get to know your archivists! Share your project with them. There’s a good chance they’ll get interested in the work you’re doing, and in turn be able to point you to further resources to enrich your work.

What can be intimidating about archival research?

In my case, what was intimidating was the sheer volume of material! I was sorting through decades of institutional records—some of which were quite tedious, documenting the minutia of museum operations. It sometimes felt like I was looking for a needle in a haystack. I’m fortunate that I persevered through this tedium, because buried within these institutional records were incredible materials that vitally illuminated many of the questions I was asking about evangelicals and their approach to presenting history in public.

Do you have a favorite collection or one that has yielded unexpected treasures?

When I was neck-deep in the research for Exhibiting Evangelicalism, Archives staff announced that they had finished processing Collection 698: Papers of Lois R. Ferm. I’d seen Ferm’s name throughout the records I examined from Collection 003, so I knew I had to dig into this newly available collection as well. I’m so glad I did. Based on the materials I examined in Collection 698, it became clear to me that Ferm was a key player in the development of the Billy Graham Musem: though she was no longer “in charge” of the process by the time Wheaton College was selected as the location for the site, she’d done extensive work in the early 1970s to envision the kind of research library and museum that would best preserve the legacy of Billy Graham and his ministry. Much of the vision that Ferm cast in these early years came to fruition at Wheaton’s Billy Graham Museum.

Moreover, I discovered in Ferm’s papers a highly educated, bold, and visionary evangelical woman. In some ways, Ferm was a quite conventional evangelical woman; yet in other ways, she defied the expectations of evangelical femininity in the 1970s and 1980s. I knew I had to introduce my readers to this fascinating person and to the critical role she played in planning for the Billy Graham Museum.

In your experience, what is the best part of archival research?

The best part of archival research are the unexpected discoveries—the things you didn’t know you’d find, or the things you didn’t even know you were looking for—that send you in generative new directions in your work. I had a few of those while researching Exhibiting Evangelicalism, including uncovering the treasure trove of relevant materials in Lois Ferm’s papers and the discovery in an unprocessed accession from Collection 3: Records of the Billy Graham Center of original scripts for some of the Museum’s earliest exhibits!

What project are you currently working on?

I’m currently working on two projects for my denomination, the Brethren in Christ Church: a biography of our foremost historian, E. Morris Sider, and a new interpretive history of the North American church in the 20th century. But I haven’t given up my interest in commemoration and Protestantism! I have a few ideas I want to pursue as a follow-up to Exhibiting Evangelicalism—but those are probably a few years down the line! I think there’s much more to be said about how American Protestants contributed to the nation’s memorial landscape and, in turn, how that landscape has shaped Protestants’ self-understanding.

Devin Manzullo-Thomas is Assistant Professor of American Religious History at Messiah University, where he also serves as the Director of the E. Morris and Leone Sider Institute for Anabaptist, Pietist, and Wesleyan Studies. His first book, Exhibiting Evangelicalism: Commemoration and Religion’s Presence of the Past, was published by the University of Massachusetts Press in 2022.