While December signifies the year’s end, this last month also marks a significant point of beginning for the stories of the fledging Illinois Institute of 1853 and the emerging Wheaton College of 1860.

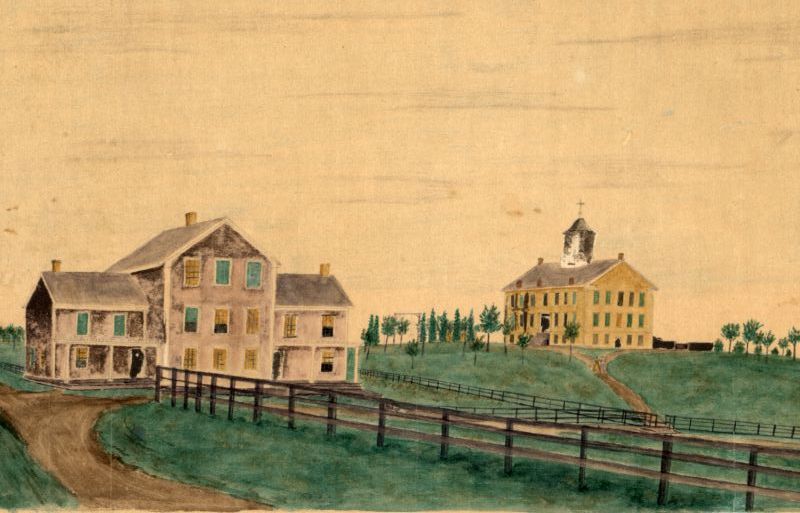

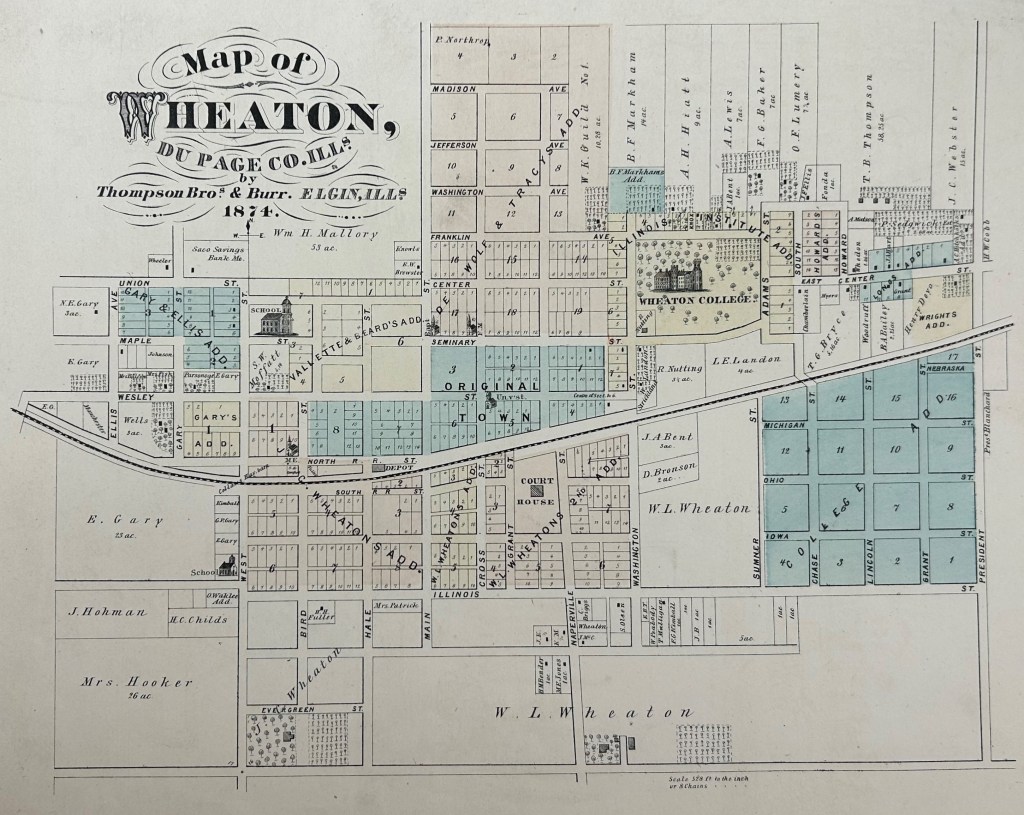

On December 14, 1853, one-hundred and seventy years ago, the first classes of the Illinois Institute were held in the basement of a incomplete stone building atop a hill in Section 16, Township 39, DuPage County. Only a small town on the Illinois prairie in the close of 1853, the location in the new Milton Township offered the advantage of legislation common to many Midwest townships that enabled the special use of land in section 16 for schools.

The new school was a project of the Wesleyan Methodist Church, which was formed in 1843 as response to ambivalence over slavery by the Methodist Episcopal Church. First envisioned in the late 1840s at the Illinois Annual Conference of the Wesleyan Methodists, leaders of the new church sought to establish a school where they could educate their children in their reform beliefs, especially the abolitionist fight against slavery. As Rufus Blanchard records in his History of DuPage County (1882), “Preparations for building began by the founders kneeling in the prairie grass on the summit of the beautiful hill…and dedicated the hill and all that should be upon it to that God in whom trusting they had boldly gone into the thickest of the fight, not only for the freedom of human bodies, but of human souls as well.”

The trustees of the new institute purchased the land in Milton Township at the bargain cost of $150 and obtained donations of $3,000 to begin building. Constructed with limestone excavated from a quarry in nearby Batavia and hauled to the site from the train station by Gaius Howard, the stone building eventually measured a respectable forty-five feet by seventy-five and consisted of two stories above the basement. The cost of the structure was about $10,000. Offering both college preparatory courses and a “common school” for children, during the first year the student body numbered 140 students, rising to 270 in the second year.

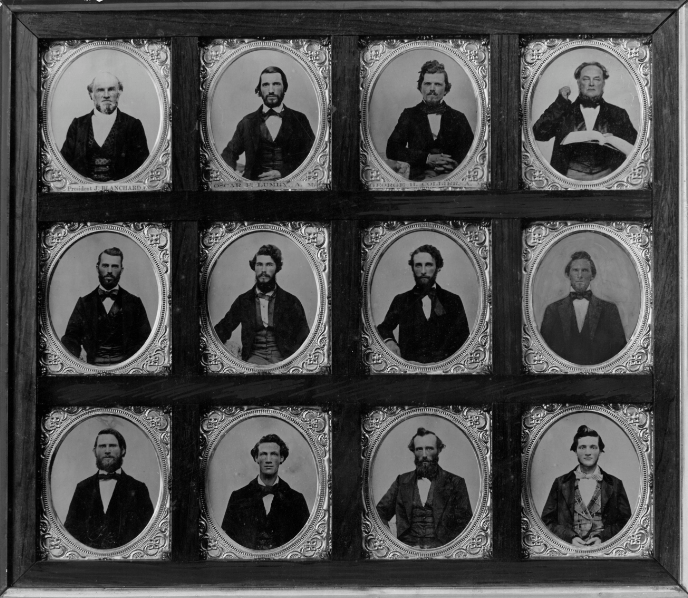

The first instructor and President was Rev. John Cross, who was active in establishing the Underground Railroad across the Midwest. The following year, after Cross left to help begin Amity College in Iowa, Rev. C. F. Winship took the helm, but shortly left to become a missionary in West Africa. Rev. George P. Kimball, fresh from Amity serving with Cross, taught alongside Miss Pierce and Rufus Blanchard until 1855 when, as Rufus Blanchard relates in his county history, Rev. J A. Marling became “Principal of the first collegiate year,” as the Illinois Institute had been chartered by the State of Illinois as a college in 1855. Professor Freeborn Garretson Baker filled in until September 1856 when Rev. Lucius C. Matlack, who had been chosen for president some years before, took on his official role as president.

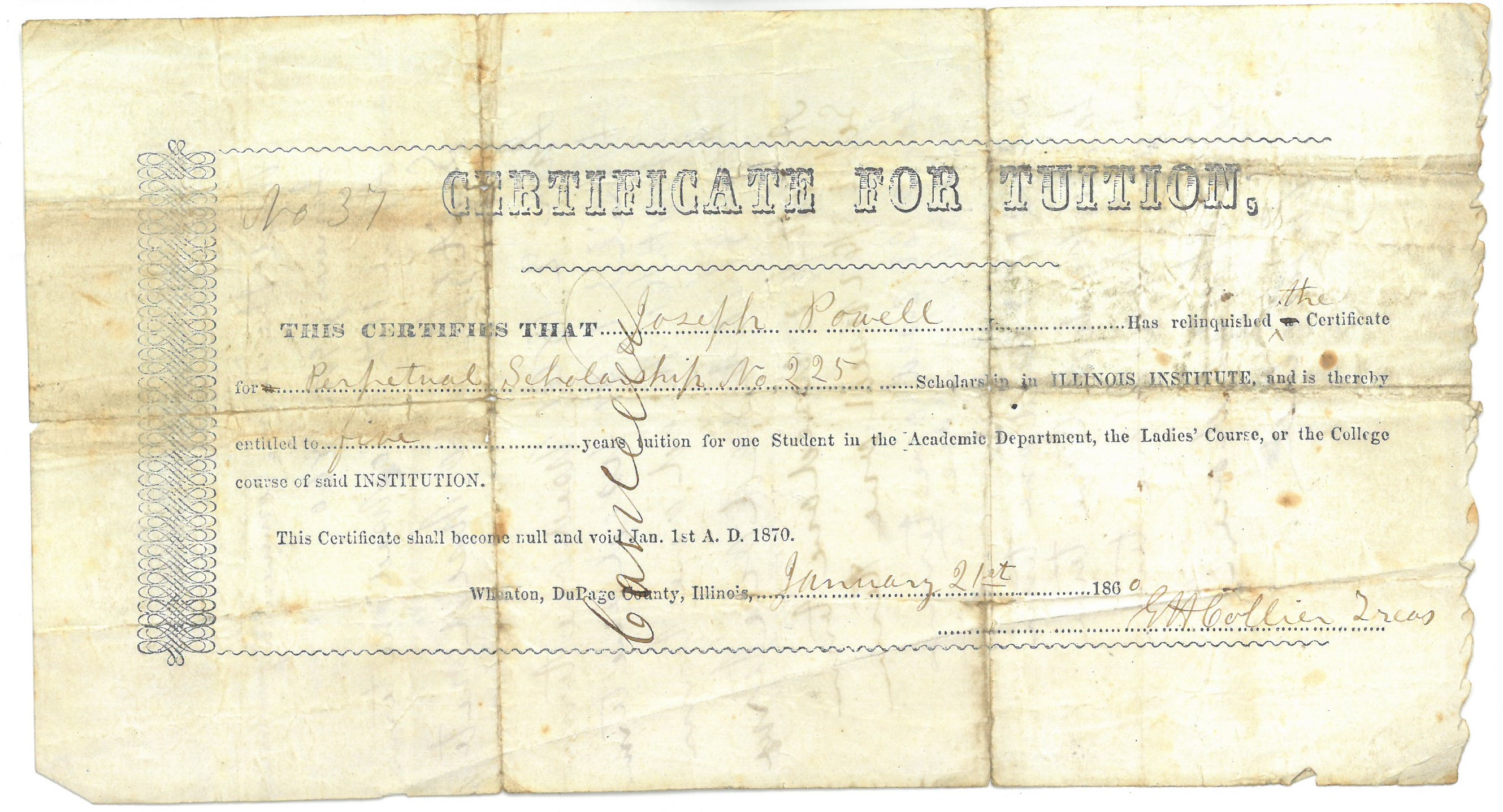

During the early years of the Illinois Institute the school rested on a solid financial foundation. The founders had secured a permanent endowment fund of $100,000 by the sale of scholarships. However, like many schools of the time, particularly Wesleyan schools, thousands of dollars in pledges went unpaid for scholarships that had been redeemed. The Illinois Institute also began receiving transfer students from other Wesleyan schools, like the Leoni School in Michigan, that were struggling financially. Compounding these internal struggles, shortly after Matlack became president, the United States experienced a significant financial crisis. Matlack did all he could to raise funds for the school but was unsuccessful. The trustees increasingly pressured him to resign as the Institute consumed its endowment and was thousands of dollars in debt. Not wanting to leave the school adrift, Matlack suggested bringing in Jonathan Blanchard who was known as a strong leader and fundraiser – having brought Knox College from the financial brink to solvency. Matlack finally resigned in 1859 noting: “I have no salary, no revenue, and am in debt.”

In the fall of 1859, the trustees followed Matlack’s counsel and approached Blanchard to accept leadership of the school on the condition that he would continue to support the school’s anti-slavery, temperance, and oath-bound societies beliefs. Blanchard agreed, but stipulated that the charter should be changed so that the trustee board be self-governing and composed as Blanchard saw fit. Despite the less than ideal circumstances, the transition was smooth and the board expanded. The Wheaton College trustee minutes for January 1860 declared “The college hereafter is to be under the control of Orthodox Congregationalists with the cooperation of its founders and our friends, the Wesleyans.”

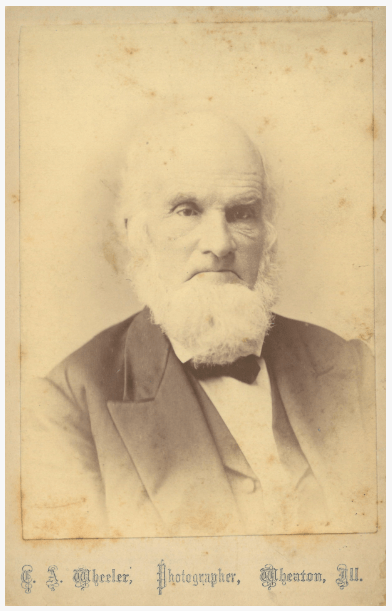

Jonathan Blanchard first arrived at the Illinois Institute in December of 1859, leaving his wife, Mary Bent Blanchard, and family in Galesburg until the circumstances became more certain. Though the financial footing of the Illinois Institute was rather shaky, Jonathan Blanchard saw a way forward through an old friend of the Institute, Warren L. Wheaton.

Warren Wheaton, along with his brother Jesse, came to the prairie beyond Chicago from Pomfret, Connecticut in the 1830s. Wheaton had served as secretary for the Institute board of trustees and was also a major benefactor to the struggling school. On December 5, 1859, Blanchard wrote to Warren Wheaton about donating fifty acres of prime real estate that was situated south of the campus beyond the railroad toward present-day Illinois and President streets.

In the letter, Blanchard plainly outlined his plan to the wealthy landowner:

Now I propose this:

1. Call the College “Wheaton College” and that will at least save your heirs the expense of a good monument;

2. Make your donation of each alternate lot of that land an outright donation to the College.

The College is already a fact and can no more be a failure than your farm can. It may yield more or less in any one year but it will be there.

RG 01.01 Jonathan Blanchard Papers, Folder 4-13.

Warren L. Wheaton agreed to the request, with the additional stipulation offered by Blanchard that substantial improvements and building projects in the amount of $25,000 be completed on the donated land within five years.

In January 1860, President Blanchard officially entered upon the duties of his office. As promised, the name of the institution was changed to Wheaton College, and the charter was amended by the Illinois Legislature of 1861. The first class of seven young men, all of them from the regular college course, graduated on July 4, 1860.

Explore more documents related to the Illinois Institute and early Wheaton College history through the College Archives.