This November, Wheaton Archives & Special Collections commemorates the 50th Anniversary of the Thanksgiving Workshop on Evangelicals and Social Concern and the resulting “Chicago Declaration.” At a time when many American evangelicals were increasingly grappling with the role of political action and social justice in American religious life, the 1973 Chicago Declaration emerged as a call for action – and a point of controversy – for a new vision of American evangelicalism grounded in social, economic, and racial justice.

Several collections in Archives & Special Collections document the development of this movement, including Collection 37: Records of Christians for Social Action and newly received papers from Ronald Sider (Accession 2022-053), which contain many folders of correspondence on the workshop planning, as well as the extensive discussions and disagreements surrounding the first drafts of the Chicago Declaration.

Background: Theological Divides and Emerging Concerns

In the early twentieth century, the growing divisions between “fundamentalists” who defended traditional Christian orthodoxy, including biblical inerrancy, and the “modernists” who embraced a more liberal interpretation of the Bible and engaged with the Social Gospel movement helped push many theologically conservative Christians away from engagement with social activism.

However, after World War II, a subset of progressive evangelical leaders increasing contested the popularly accepted division between conservative orthodoxy and social justice. In 1947, Carl Henry published his influential book The Uneasy Conscience of Modern Fundamentalism. In the 1960s, Black evangelists like Tom Skinner and Bill Pannell challenged the biases and racial injustices of the American evangelical church. And the start of the 1970s saw an emerging integration of missiology and social activism from Latin American thinkers like René Padilla and Samuel Escobar.

In this atmosphere of change, George McGovern, the evangelical Christian, and politically liberal Senator, launched his 1972 campaign for President against the incumbent Richard Nixon. Following his confirmation as the Democratic candidate, a group of progressive evangelical Christians, led by Messiah University professor Ronald Sider, founded “Evangelicals for McGovern” to promote McGovern’s campaign – and its stance on peace in Vietnam and other social concerns – among American evangelicals. Although “Evangelicals for McGovern” had only limited success in fundraising and Nixon handily defeated McGovern in the November election, the brief campaign fostered new ties between evangelical leaders interested in a more progressive approach to biblical social concern. After McGovern lost the race, Sider, and others involved in the campaign, like Richard Pierard, John Alexander, Robert Webber, and David Moberg, sought to continue their work for renewed Christian social action beyond the limitations of a specific candidate or office.

The Thanksgiving Workshop

At the Conference on Christianity and Politics at Calvin College in April 1973, a committee of evangelical leaders, including John Alexander, Myron Augsburger, Paul Henry, Rufus Jones, David O. Moberg, William Pannell, Richard Pierard, Ronald J. Sider, Lewis Smedes, and Jim Wallis, began planning a Thanksgiving Workshop on Evangelicals and Social Concern. Arguing that American evangelicalism had drifted too far from biblical injunctions to care for the poor and oppressed, they decided to gather in Chicago in November of 1973 to discuss the role of social activism in the Christian life and church.

The centerpiece of the workshop was to be the creation of a declaration on the need and purpose for evangelical social action, along with proposals for potential ways to implement a distinctly evangelical social activism. A memo to the participants in August 1973 expressed the hope that the declaration would be a “prophetic document” guiding evangelicals toward a more comprehensive embrace of the biblical concern for the well-being of all people (CN37, Folder 1-11).

The Thanksgiving Workshop began on November 23rd at the YMCA on S. Wabash in Chicago, bringing together a diverse group of 52 participants from across the United States.

While discussion and debate on the proposed declaration remained the core of the Workshop, smaller groups were also formed to consider topics and propose action steps on Christian Lifestyle, Publication & Education, Sexism, Racism, and Political-Social-Economic Involvement. At the conclusion of these break-out sessions, participants put forward a wide range of proposals, from founding an Evangelical Center on Race Relations or the participation of evangelical caucuses at party conventions to increased support and resources for education and research on social issues, systems, and socio-historical critiques.

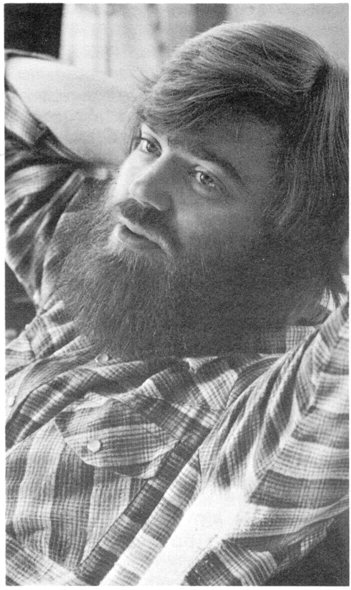

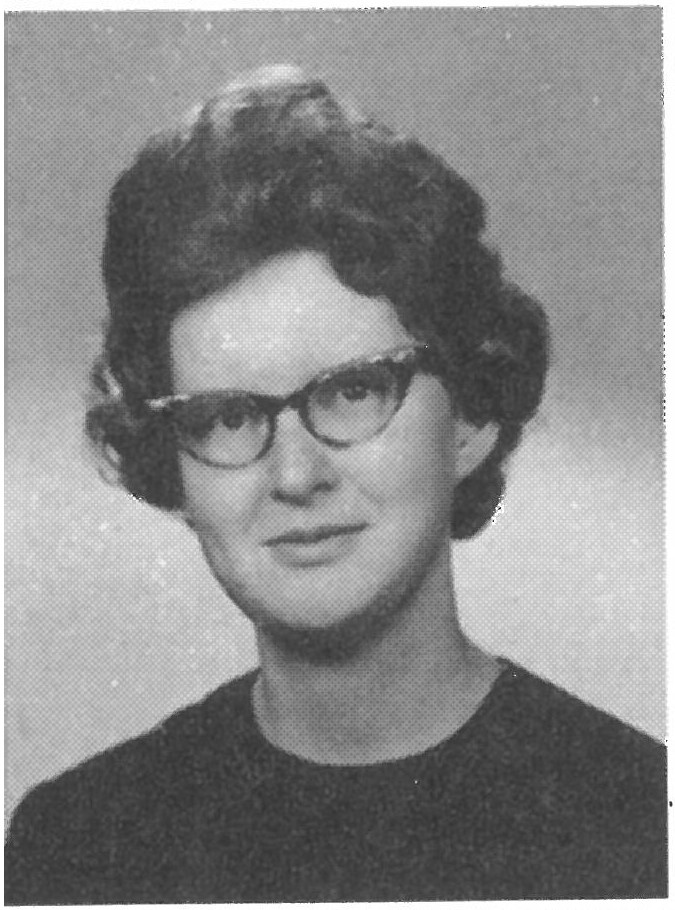

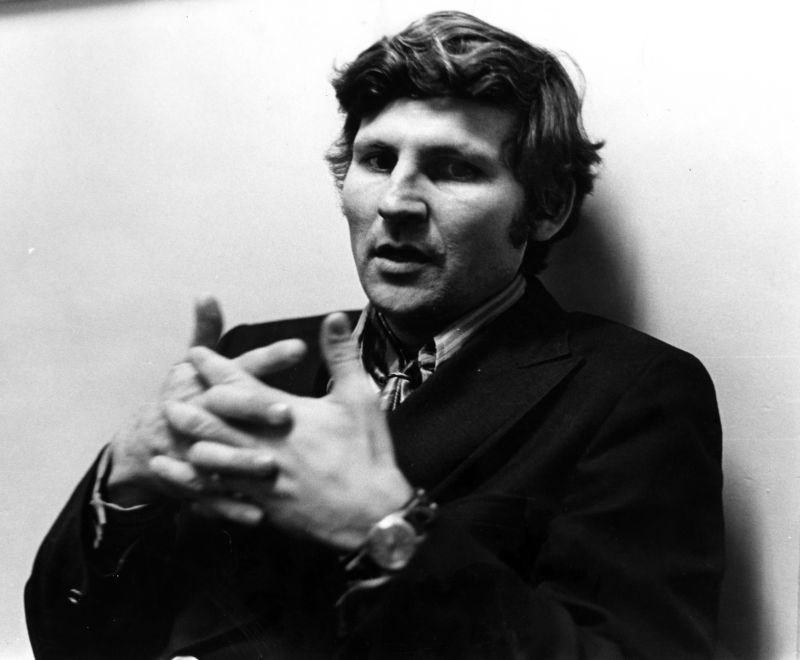

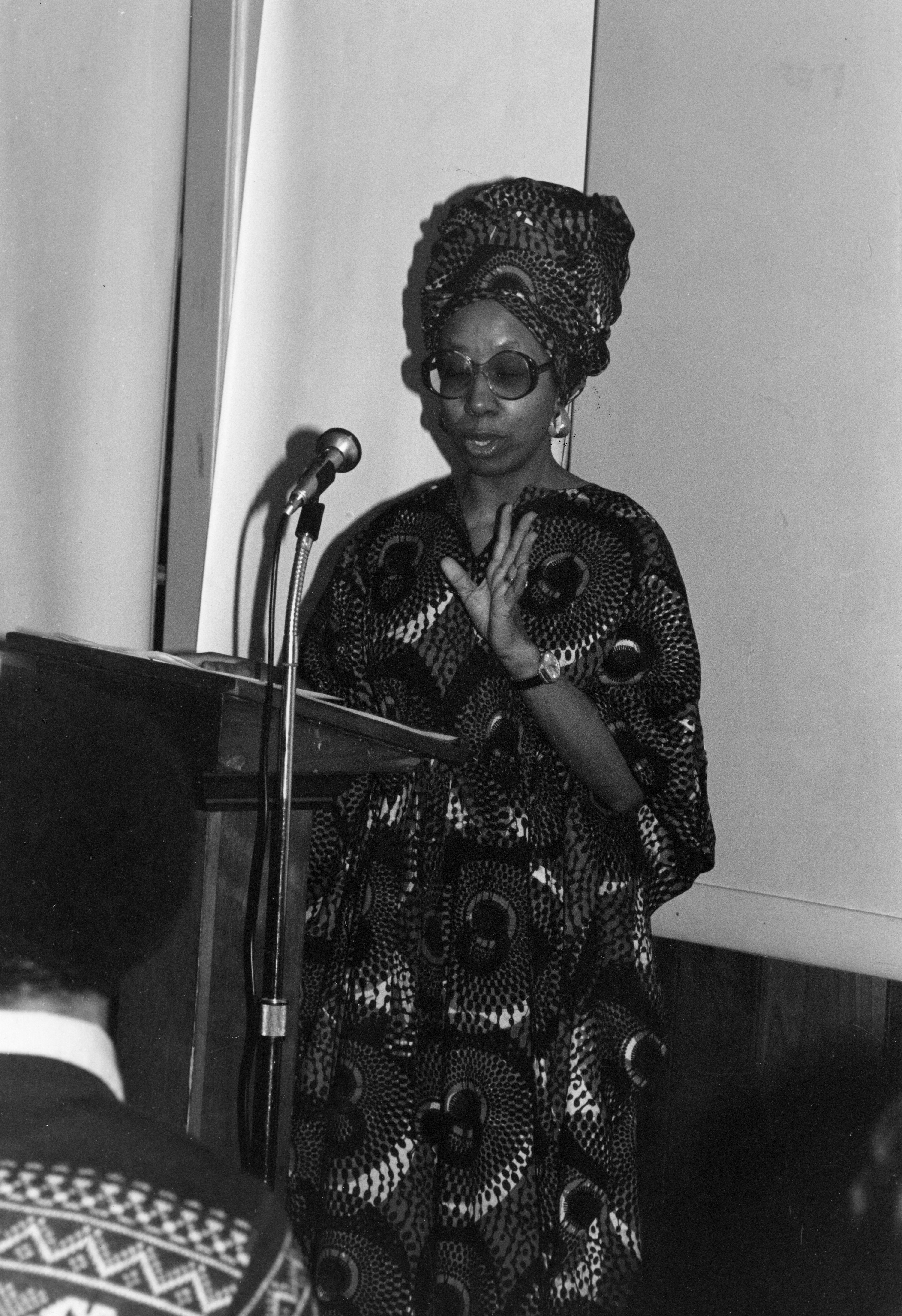

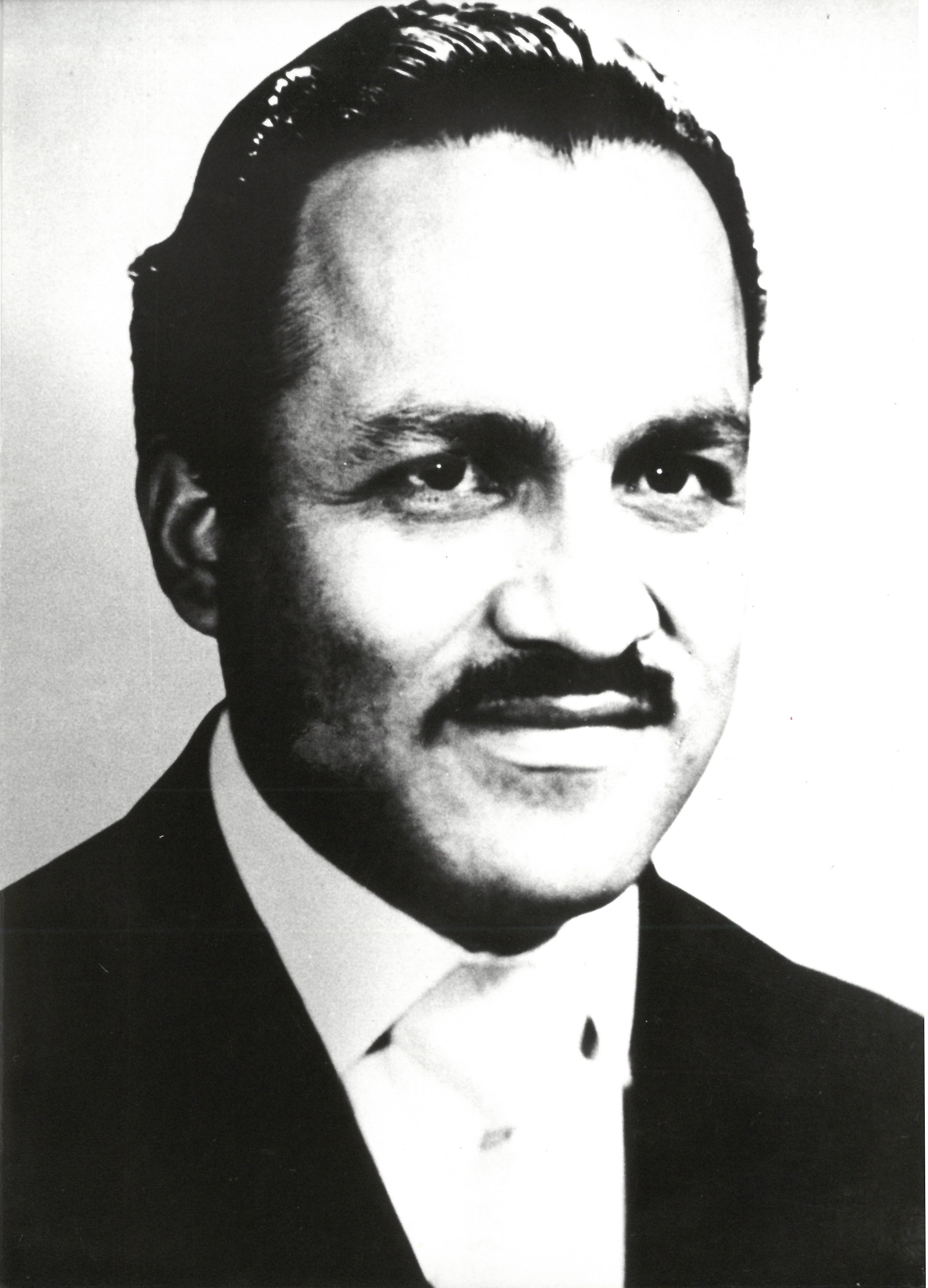

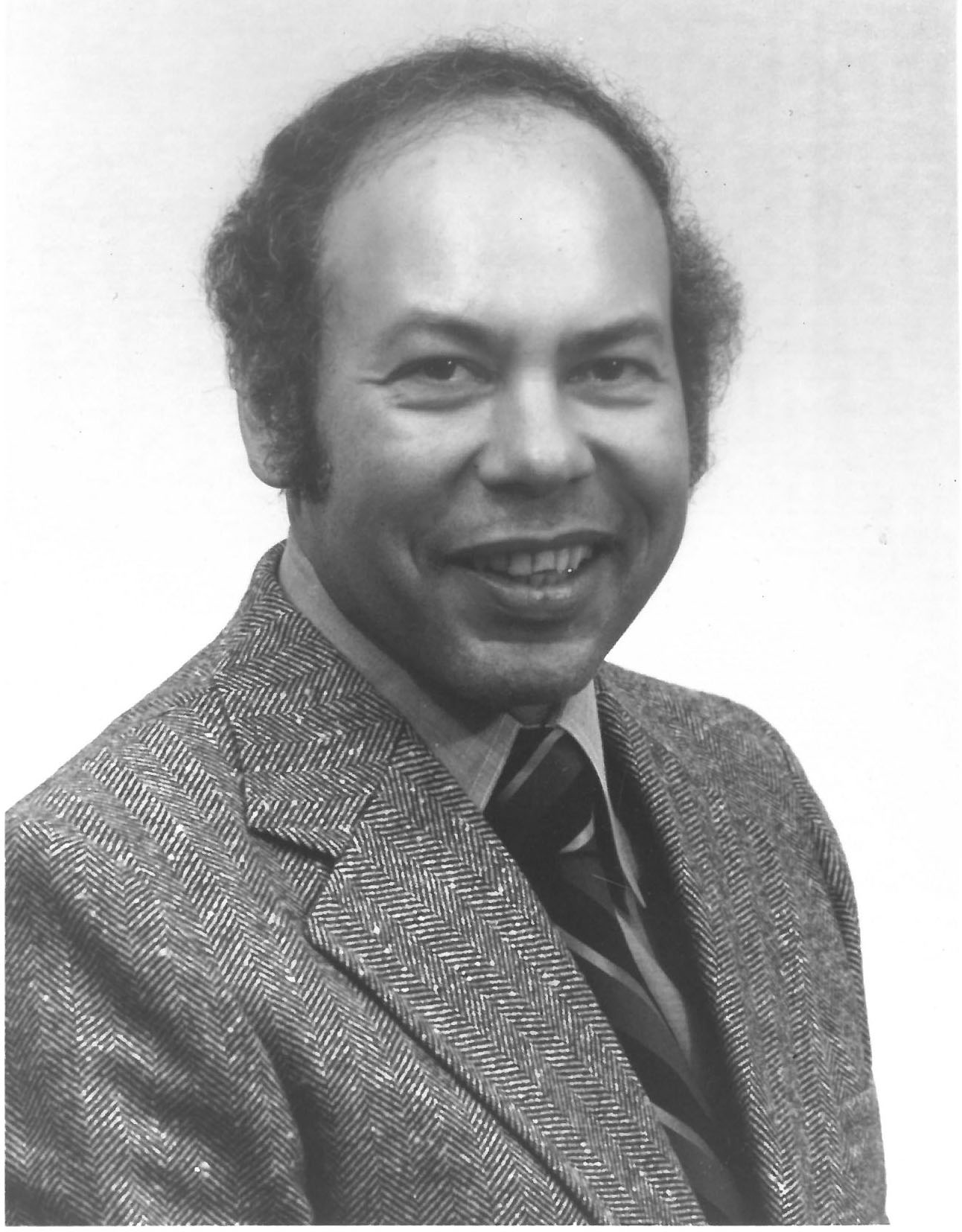

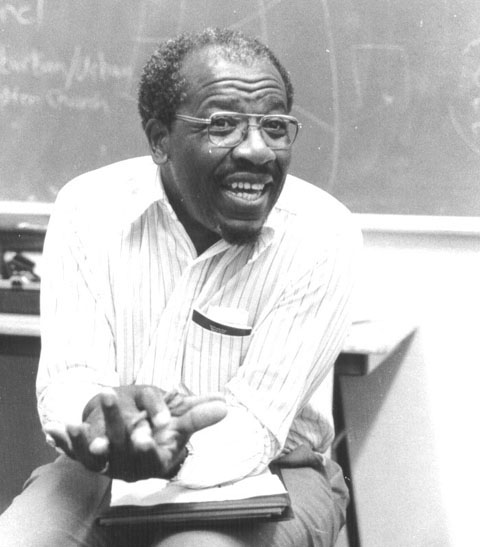

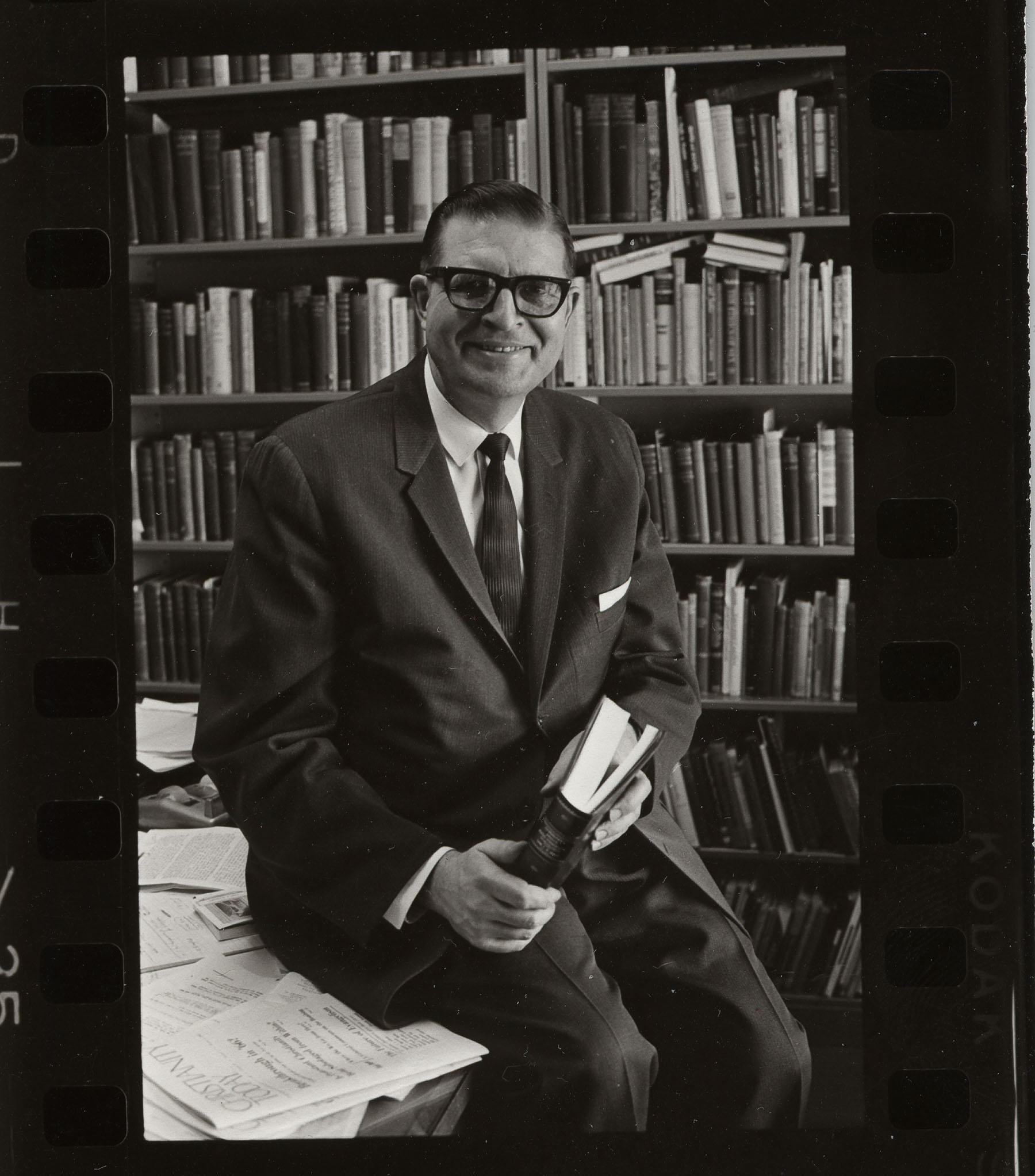

Eight of the 52 participants in the 1973 Thanksgiving workshop. For a full list, see the program for the workshop.

The Chicago Declaration

Throughout the planning process and into the workshop, members of the planning committee and participants struggled to succinctly define a plan of action or agree upon goals for collective evangelical social action. While united in their belief on the biblical injunction for justice, there remained considerable disagreement on the methods, direction, and theological boundaries for such a project. Working on the shape and language for the declaration, more conservative members insisted on a clear commitment to evangelical Christian orthodoxy, Black participants like Bill Pannell and William Bentley, and the few women participants, including Wheaton College graduates Nancy Hardesty and Ruth Bentley, pushed for language highlighting the evangelical church’s complicity in racism and sexism and the need for repentance and reform. For further analysis of the various tensions and disagreements surrounding the development of the declaration, see historian David Swartz’s excellent series on Ronald Sider and the Chicago Declaration from the blog Anxious Bench.

Although the various factions and disagreements were never resolved entirely, at the conclusion of the workshop, the participants completed and signed the statement, “A Declaration of Evangelical Social Concern,” which later became known simply as “The Chicago Declaration.” In the statement, the signatories confessed their participation in forms of racism and exploitation and pledged to “rethink their lifestyle and work for a more just distribution of the world’s resources.”

Reflecting on his experience at the Thanksgiving Workshop, Frank Gaebelein concluded, “that such a varied and trans-denominational gathering, after two days of rigorous and sometimes unsparing discussion, succeeded in forging, and with near unanimity, agreeing on a Declaration that goes well beyond what has been said on social matters by any comparable evangelical group—This was an event of genuine significance…. For a succinct statement of evangelical social concern had first of all to be thought through and adopted as a basis for more faithful discipleship in this area” (2022-53, Box 19).

Legacy and Impact

The Chicago Declaration, while not without criticism – from both the right and the left – offered a clear Evangelical challenge to the accepted divide between conservative orthodoxy and social justice, emphasizing the biblical call to care for the marginalized and oppressed.

The novelty of evangelical Christians appearing to support liberal social policies led to extensive coverage of the workshop and declaration in the Christian and secular press. Seeking to capitalize on this interest and generate new support, Ron Sider, encouraged by Robert Webber, sought to publish the text of the declaration along with edited remarks from workshop participants. In 1974, “The Chicago Declaration” was published and distributed through Webber’s Creation Press.

While immediate press interest had been high, the lasting legacy of the workshop and declaration was mixed. A group of evangelical leaders met for a second meeting in November 1974 and these meetings became the basis for the Evangelicals for Social Action (now Christians for Social Action), which was officially launched as a national membership organization in 1978, with Ron Sider as its first president. Other participants from the initial workshop, including Jim Wallis, John Alexander, William Pannell, Ruth and William Bentley, among many others, also continued to advocate for a biblical view of social justice through their own ministries and organizations. However, a broader shift in American evangelical Christian culture toward increased engagement in social activism did not materialize and, like the brief Evangelicals for McGovern campaign, the evangelical left had only limited success on the political front through the 1970s and 80s.

The 1973 Chicago Declaration challenged evangelicals to reconsider their stance on social justice and helped inspire individuals and organizations to promote a more holistic approach to faith. The declaration stands as a testament to the power of dialogue to effect change and the enduring Biblical call to work towards a more just and compassionate society.

In addition to the records of Christians for Social Action, Archives & Special Collections holds several collections documenting individuals and organizations involved in evangelical social action through the 1970s and beyond. A few of these include: SC-023: Records of Sojourners, SC-182: Records of The Other Side, CN 326: Records of Voice of Calvary Ministries, and oral history interviews with Bill Pannell, Tom Skinner, and C. René Padilla.

Pingback: Where Did Evangelicals Go Wrong? | Ordinary Chaos

Pingback: Where Did Evangelicals Go Wrong? - The New York Folk

Pingback: Where Did Evangelicals Go Wrong? – Parlour News Media

Pingback: The place Did Evangelicals Go Incorrect? - moneytree7.com

Pingback: Where Did Evangelicals Go Wrong? - Maniota

Pingback: Where Did Evangelicals Go Wrong? - Health and Fitness

Pingback: The place Did Evangelicals Go Mistaken? - livingdailyy

Pingback: The place Did Evangelicals Go Mistaken? - Noor Jani

Pingback: Where Did Evangelicals Go Wrong? – More GoGIGA Original

Pingback: Peter Wehner in The Atlantic. Where Did American Evangelicalism Go Wrong? Plus a Reflection on Being an Evangelical Means Living in a Constant State of Chaos | Wondering Eagle