The origins of Black History Month can be traced back more than a century to Carter G. Woodson, who founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH) in 1915, after attending the fiftieth anniversary celebrations for national emancipation in Chicago. As part of its efforts to draw attention to the study of Black history and culture, the Association established Negro History Week in February 1926. Observance gradually gained national traction, especially during the 1960s, as a growing number of college students organized campus events highlighting Black culture and urged universities to established courses and academic departments dedicated to Black history or literature. In 1976, President Gerald R. Ford officially recognized February as Black History Month, and Congress formally institutionalized its observance ten years later in Public Law 99-244.

In keeping with national trends, Wheaton College’s earliest organized observances of Black history and culture took shape with the student-led “Black Arts Festival,” inaugurated in the spring of 1969.

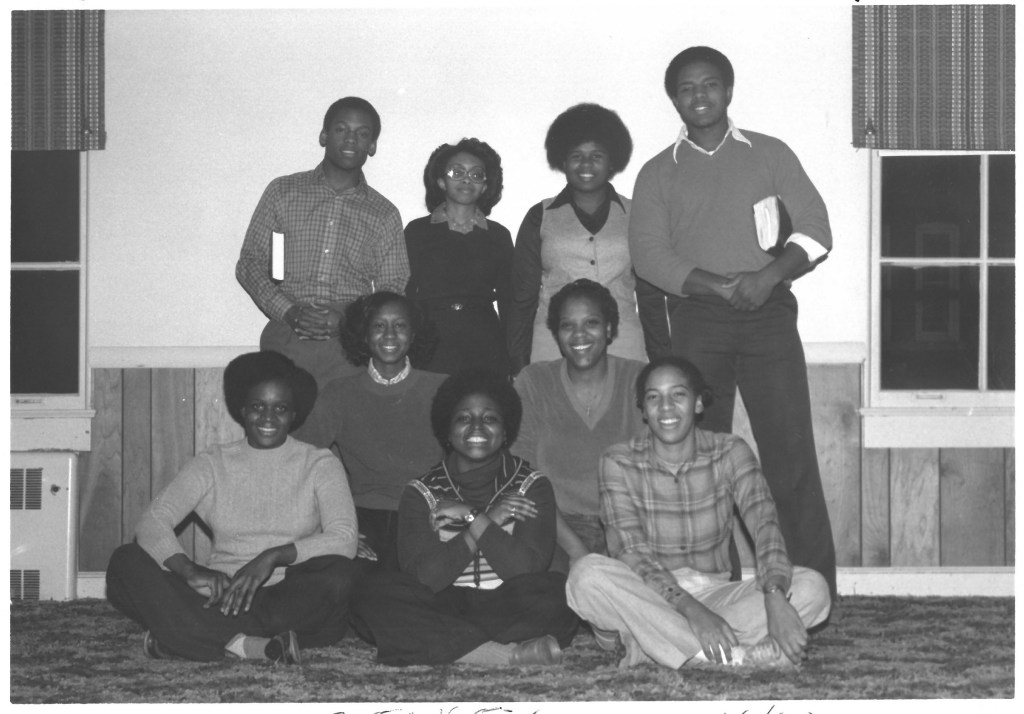

While Wheaton College had enrolled students of color since the 1860s, their numbers had typically remained small. The introduction of the Compensatory Education Program (CEP) in the fall of 1968 brought a notable increase of Black and Puerto Rican students to campus from urban centers around the United States, like Chicago or New York. Adjusting to life in suburban Wheaton, CEP students sought to form an organization that would both foster solidarity among minority students and educate a predominantly white campus community. Under the guidance of Dr. Ozzie Edwards, Wheaton’s only Black faculty member at the time, students founded the Student Organization for Urban Leadership (SOUL) in early 1969. The organization quickly turned its attention to planning a week-long celebration dedicated to Black art, music, and culture.

SOUL gave their new festival the theme “Si Si,” a Swahili word meaning “we” or “us.” Reflecting on this theme of unity amid difference, The Wheaton Record reported that SOUL: “express[es] hope that their Festival will be received biculturally by the rest of the campus and community…. that they desire that one culture not be judged by the standards of another, but that it be viewed as an entity in itself.” (The Wheaton Record, “Students Announce Plans for Black Arts Festival,” April 1969).

Plans for the festival included lectures from Charles Campbell, a Cook County Jail chaplain, on “What It Means to Be Black” and James Turner, a Northwestern University scholar and activist, on “The Black Student on the White Campus,” along with a film screening of Nothing But a Man and an exhibition from Chicago artist Lucille Cunningham.

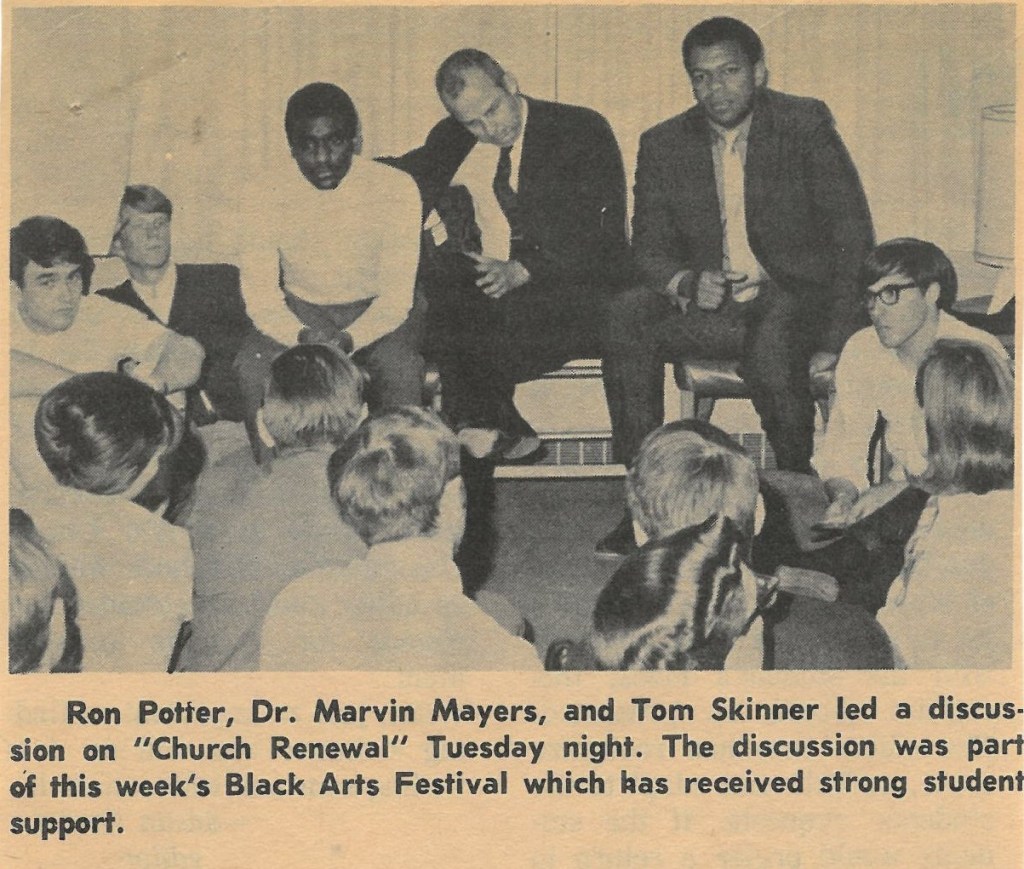

Serendipitously, the festival coincided with Wheaton’s Spring Special Services, which that year featured influential Black evangelist Tom Skinner as speaker. Although not planned in conjunction with the Black Arts Festival, Skinner’s chapel series on the radical love and grace of Jesus Christ and his critique of the white evangelical church’s failure to embody a multicultural Christian community provided a stirring complement to SOUL’s efforts.

Reflecting on the Black Arts Festival in the May 2, 1969 issue of The Wheaton Record, Wheaton freshman and SOUL member Ron Potter wrote, “We wanted to portray the culture of the black man today. But more importantly, we hoped the week would challenge students and faculty to grapple with the problems of racism and injustice in our society.”

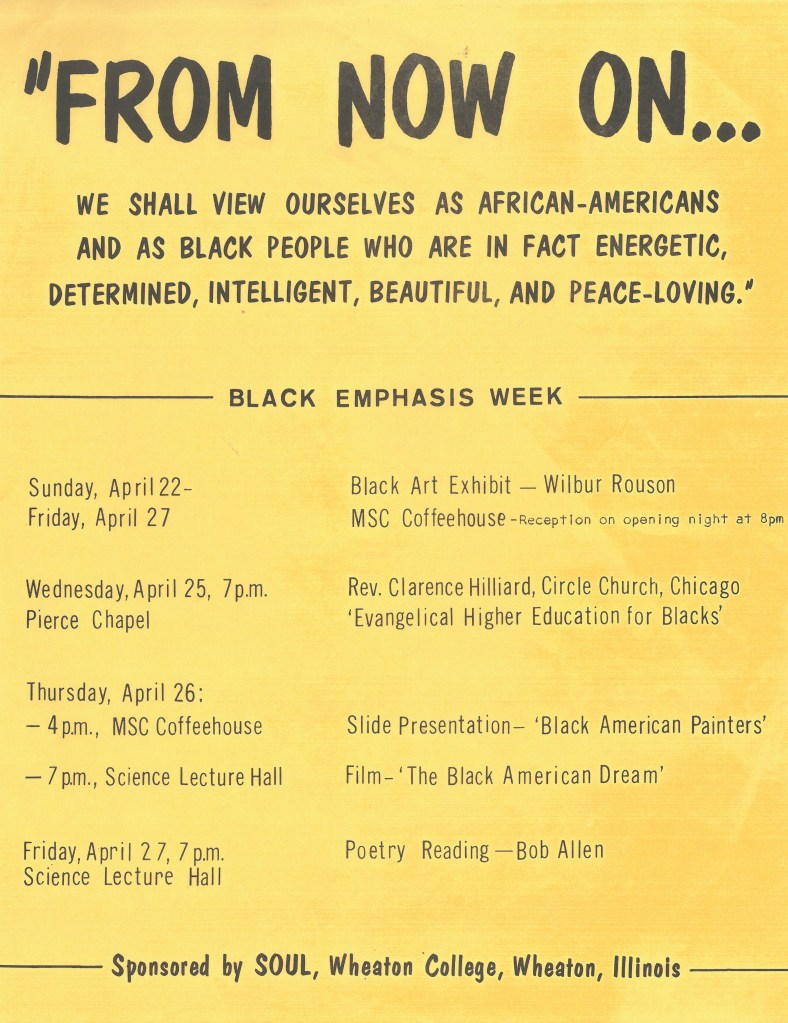

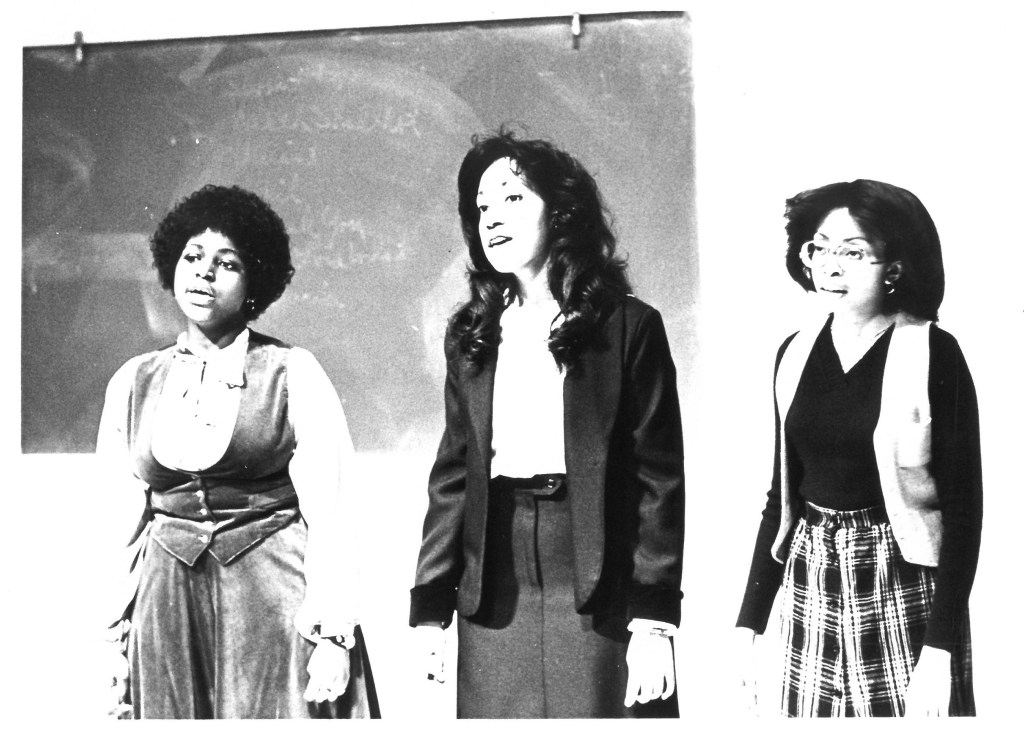

Over the next decade, the festival continued to celebrate and showcase Black culture through a wide range of programming, offering film screenings for The Black American Dream (1973), Brian’s Song (1974), and Man and Boy (1975); exhibiting artists like Wilbert H. Rousen (1973), Lucas Mahnard (1978), Baba Alabi S. Ayilina (1979); and staging dramatic presentations, including theatrical readings from the works of Frederick Douglas and Malcolm X (1973), the amateur Black theater troupe Playward Bus Theatre Company (1974), and student-led set pieces from plays like A Raisin in the Sun (1975).

Music also became an integral part of the festival. Programming regularly included gospel choirs from local Black churches, as well as special performances from musicians like the Afro-Jazz group Irasemacungas (1970), the Metropolitan Opera star Shirley Verrett (1974), the gospel rock band Soul Liberation (1977), and Daniebelle Hall, former lead singer with Andrea Crouch and the Disciples (1979).

In 1975, under the leadership of Matthew Parker, Wheaton’s newly appointed Minority Student Advisor, the Black Arts Festival was moved from April to February to align with the growing consolidation of Black History Month celebrations. Announcing that year’s festival titled “Looking Up and Moving On” in The Wheaton Record, Matthew Parker framed the festival as a way to “introduce Wheaton College to other cultures within Wheaton and America and to learn about other humans in terms of their past and present condition and where they are going from here” (The Wheaton Record, January 31, 1975).

Beyond its artistic offerings, the festival also sought to invite campus reflection on race, faith, and community. Guest speakers like Rev. Clarence Hilliard (1973), Rev. Henry Soles (1975), Dr. Ruth Lewis Bentley (1977), and Dr. Mary Lennox (1978) addressed pressing questions of racial justice, identity, vocation, and multicultural community.

Campus response to SOUL and its annual festival were often mixed. Although The Wheaton Record noted strong attendance for the inaugural Black Arts Festival in 1969, reports in subsequent years sometimes featured student commentary lamenting low participation and a perceived lack of campus interest. The 1973 festival encountered a more overtly hostile reaction, when some of the posters for Black Emphasis Week were removed or defaced.

However, other students and faculty on campus celebrated SOUL’s efforts. Prefacing a 1978 SOUL event, Arthur Volle, Wheaton professor for education and member of the Minority Student Affairs Committee, reflected:

“During that period before the late 1960s none of us really had much awareness of the magnitude of the problem of racial injustice in our country. Right here in Wheaton, Christians who were very active in keeping liquor out of our city – or keeping our city from having a 4th of July parade on a Sunday afternoon, failed to speak out against a system of gross injustice which forced people like Ozzie Edward to live in a segregated area south of the tracks. I am ashamed to admit that I was one of those who was silent at that time. Then during the violent period of the late 60s following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, many of us were jarred into consciousness of the terrible injustice we were tolerating, and a number of faculty members and administrators joined in an effort to pass an open housing ordinance in Wheaton. During that time a number of us also became aware of the desperate need for Christian leadership in minority communities. And we began to look for ways in which Wheaton College might help develop that leadership. We made a lot of mistakes during the early years of the Compensatory Education Program’s existence – and I think the mistakes we made were due to our own cultural deprivation. We had no understanding of the minority students’ cultural background, and so we couldn’t properly respond to their needs. We did learn a lot from these students… They didn’t hesitate to tell us what was wrong with the program. We also learned from our Black pastor friends and from other Christian Black leaders.”

Arthur Volle, 1978. From RG 7.8: Student Development Records, Box 19, Folder 22.

In 1975, SOUL helped launch BRIDGE (Building Relationships in Discipleship, Grace, and Experience) to create a space that welcomed students from diverse cultural backgrounds. SOUL was officially incorporated into BRIDGE in 1981. The larger organization continued the annual festival as the Multicultural Arts Festival until 1989, when BRIDGE was also disbanded due to student disagreements about the organization’s structure and activities. Over the next few years it was replaced by smaller solidarity student groups like the William Osborne Society, Asian Friday Night Fellowship, and the Hispanic Student Union.

Explore additional records documenting student life and culture through the Wheaton College Archives, or learn more about SOUL, BRIDGE, and the history of race relations at Wheaton College in Wheaton’s Historical Review Task Force Report (2023).