The origins of Black History Month can be traced back more than a century to Carter G. Woodson, who founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH) in 1915, after attending the fiftieth anniversary celebrations for national emancipation in Chicago. As part of its efforts to draw attention to the study of Black history and culture, the Association established Negro History Week in February 1926. Observance gradually gained national traction, especially during the 1960s, as a growing number of college students organized campus events highlighting Black culture and urged universities to established courses and academic departments dedicated to Black history or literature. In 1976, President Gerald R. Ford officially recognized February as Black History Month, and Congress formally institutionalized its observance ten years later in Public Law 99-244.

In keeping with national trends, Wheaton College’s earliest organized observances of Black history and culture took shape with the student-led “Black Arts Festival,” inaugurated in the spring of 1969.

While Wheaton College had enrolled students of color since the 1860s, their numbers had typically remained small. The introduction of the Compensatory Education Program (CEP) in the fall of 1968 brought a notable increase of Black and Puerto Rican students to campus from urban centers around the United States, like Chicago or New York. Adjusting to life in suburban Wheaton, CEP students sought to form an organization that would both foster solidarity among minority students and educate a predominantly white campus community. Under the guidance of Dr. Ozzie Edwards, Wheaton’s only Black faculty member at the time, students founded the Student Organization for Urban Leadership (SOUL) in early 1969. The organization quickly turned its attention to planning a week-long celebration dedicated to Black art, music, and culture.

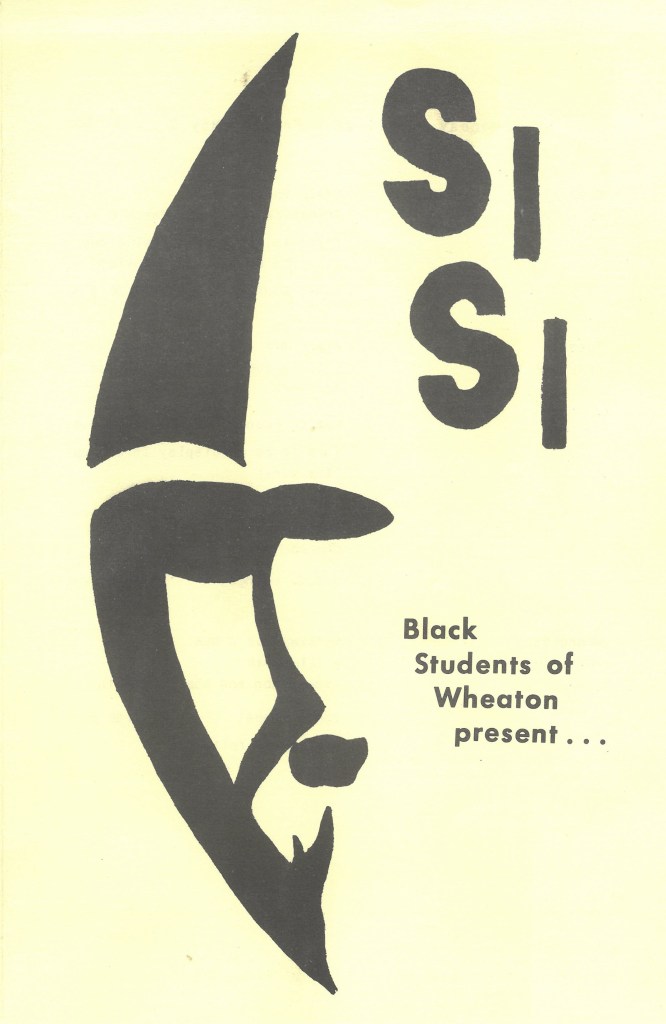

SOUL gave their new festival the theme “Si Si,” a Swahili word meaning “we” or “us.” Reflecting on this theme of unity amid difference, The Wheaton Record reported that SOUL: “express[es] hope that their Festival will be received biculturally by the rest of the campus and community…. that they desire that one culture not be judged by the standards of another, but that it be viewed as an entity in itself.” (The Wheaton Record, “Students Announce Plans for Black Arts Festival,” April 1969).

Continue reading