This March, in honor of Women’s History Month, Wheaton Archives and Special Collections remembers Vida Chenoweth—a concert marimbist, Bible translator, and pioneering ethnomusicologist. From the glittering concert halls of Europe to the remote highlands of Papua New Guinea, Vida’s life and ministry combined a love of music with a deep commitment to the dignity of all peoples and a celebration of the unique traditions of diverse musical cultures. SC 114: Vida Chenoweth Papers showcase the breadth of her remarkable career, featuring recital and field recordings, photographs, press clippings, original research, correspondence, and diaries.

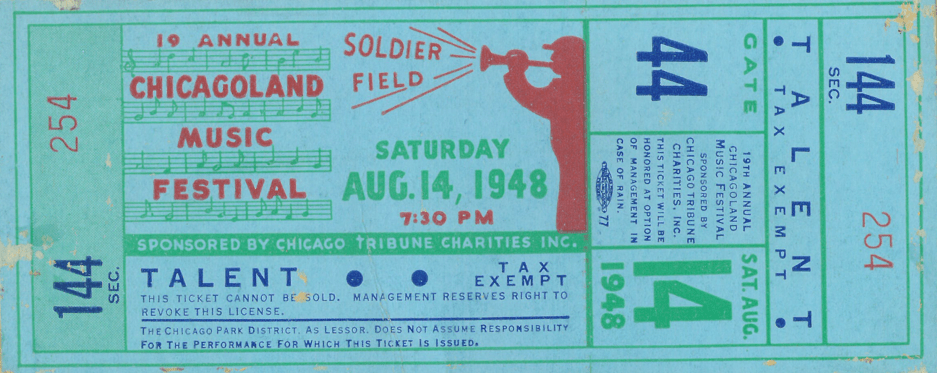

Born in 1928 to a prominent music merchant in Oklahoma, Vida Chenoweth grew up surrounded by music, with piano and clarinet lessons begun at an early age. When she was twelve years old, her father introduced her to a new instrument – the marimba. A pitched percussion instrument played with mallets, the marimba had been widely popular in Central and South America for centuries but was only introduced to the U.S. in 1908. Intrigued by the possibilities of the new instrument, Vida committed her considerable talents to mastering the marimba. A large scrapbook in the Chenoweth Papers documents many of her early recitals and competitions, including her first-place win at the 1948 Chicagoland Music Festival.

In 1949, Vida matriculated at Northwestern University’s School of Music, which offered the first U.S. degree program for marimba performance under the virtuoso Clair Omar Musser. However, her studies came to an abrupt halt during her senior year when Vida, and her twin sister Vera, were diagnosed with serious heart problems. At the time, heart surgery was in its infancy. Both sisters underwent the procedure, but while Vera tragically died in surgery, Vida—after six months of grief and painful deliberation—had a successful operation in Boston. A year later she was touring the Midwest giving solo recitals under the auspices of the University of Wisconsin.

Although supported by musical mentors at Northwestern and the American Conservatory of Music, Vida struggled to find a place in a classical music world that was still heavily centered on traditional European musicality and instruments. Making a living by giving marimba lessons in the North Shore suburbs and taking part-time jobs in the Loop, Vida worked for two years to save enough to hire the Chicago Art Institute’s Fullerton Hall where she gave in November 1953 the first public recital of classical works written for the solo marimba. Marveling at Vida’s original technique for playing polyphonic music through individual mallets, Chicago’s leading music critic Felix Borowski wrote of the performance for the Sun Times: “…remarkable. Moreover, the performer is blessed with fine musical taste. The nuances obtained were of moving beauty.”

With a letter of introduction from Rudolph Ganz, president of the Chicago Musical College, to Steinway Hall in New York City, Vida left Chicago for one of classical music’s biggest stages. Many of the leading concert managers had offices in Steinway Hall, and the way to be heard was to audition for them in the recital hall. In grey knee-sox, sandals and dirndl skirt, Vida pushed her 50-pound marimba cases one by one across the sidewalk from a Checker cab and tied up pedestrian traffic for ten minutes when one of the cases got stuck in the revolving door. Cautious of the young musician and her unusual instrument, the concert managers sent their secretaries downstairs to hear the audition. Leaping into a virtuosic Bach number, Chenoweth so astonished and excited the secretaries that they immediately fled to get their bosses to listen. In short order, Vida was onstage, debuting with her marimba at New York’s Town Hall on November 19, 1956.

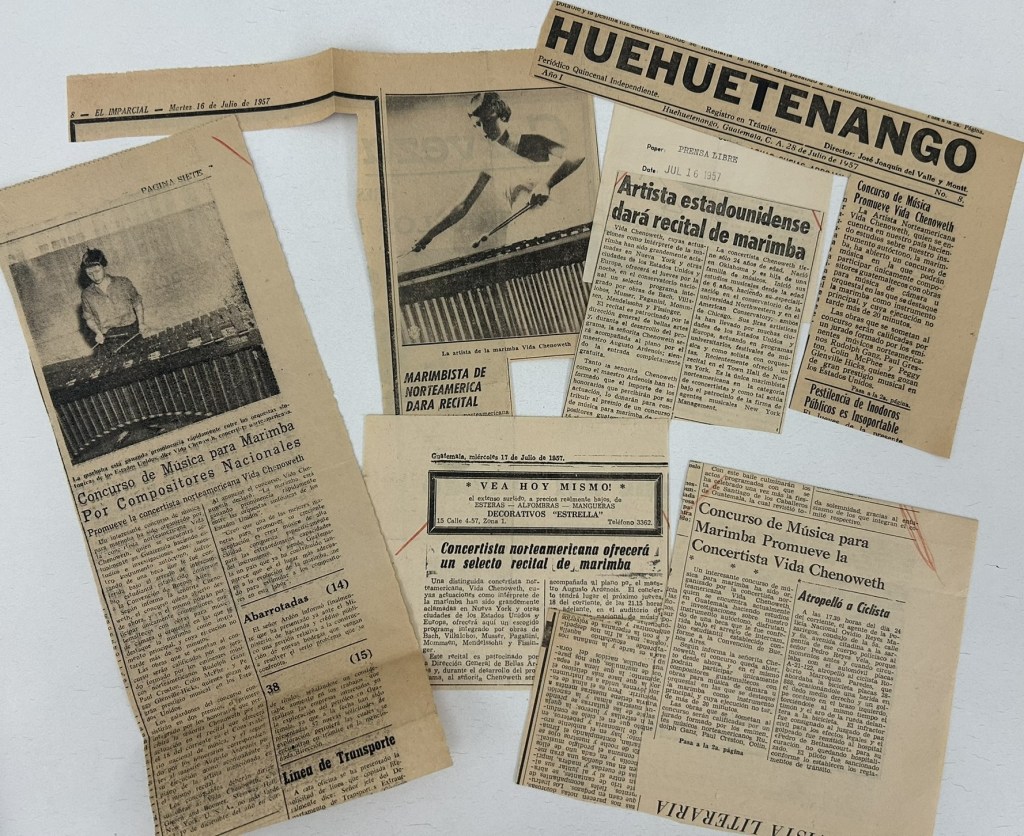

After Vida’s success in Chicago and New York, she won a Fulbright Scholarship in 1957 to study the marimba in Guatemala. Along with a busy schedule of performances across Guatemala and Mexico, Vida conducted a historical and musical analysis of the development of the marimba, culminating in her 1964 publication The Marimbas of Guatemala. Several clippings books in the Chenoweth papers document the extensive press coverage of this early performance tour, along with her later concerts around the world.

Returning to New York, Vida continued to pursue her performance career. In 1959 she became the first marimba soloist to perform at Carnegie Hall, featured in the premier of Robert Kurka’s Concerto for Marimba and Orchestra. Critics at the major New York newspapers and music magazines, as well as Time magazine, wrote rave reviews. The performance led to invitations to play throughout the world, including with the Cleveland Orchestra, New York Summer Festival Orchestra, Oklahoma City Symphony, and the National Symphony of Guatemala, among many others across Europe, Asia, and North and South America. In 1962, Vida also made the first commercial recording of concerto marimba music for Epic Records. At that time, her prominence in the instrument was such that every major classical composition for marimba except four was written explicitly for Vida.

Despite her musical success, after experiencing a personal spiritual crisis and revival in 1959, Vida increasingly felt a call to Christian service. For a year she struggled with the idea of abandoning the career she had worked so hard for and the music she loved. Then, in 1962, a gas stove accident that severely burned her hands forced her to confront a future away from the concert stage. Recovering in the hospital and unsure if she would ever play again, Vida read about Wycliffe Bible Translators and was inspired by Wycliffe’s mission to bring the Gospel to every people group in their own tongue. Although Vida eventually recovered full use of her hands, she decided to leave New York for Wycliffe’s Summer Institute of Linguistics.

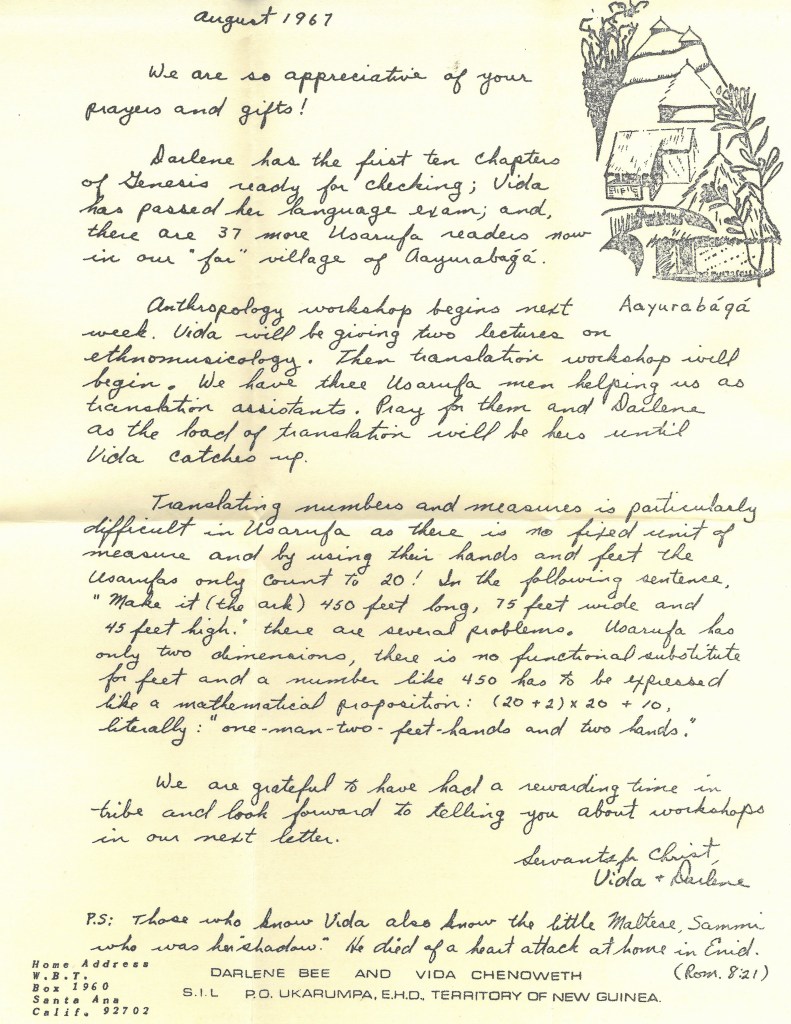

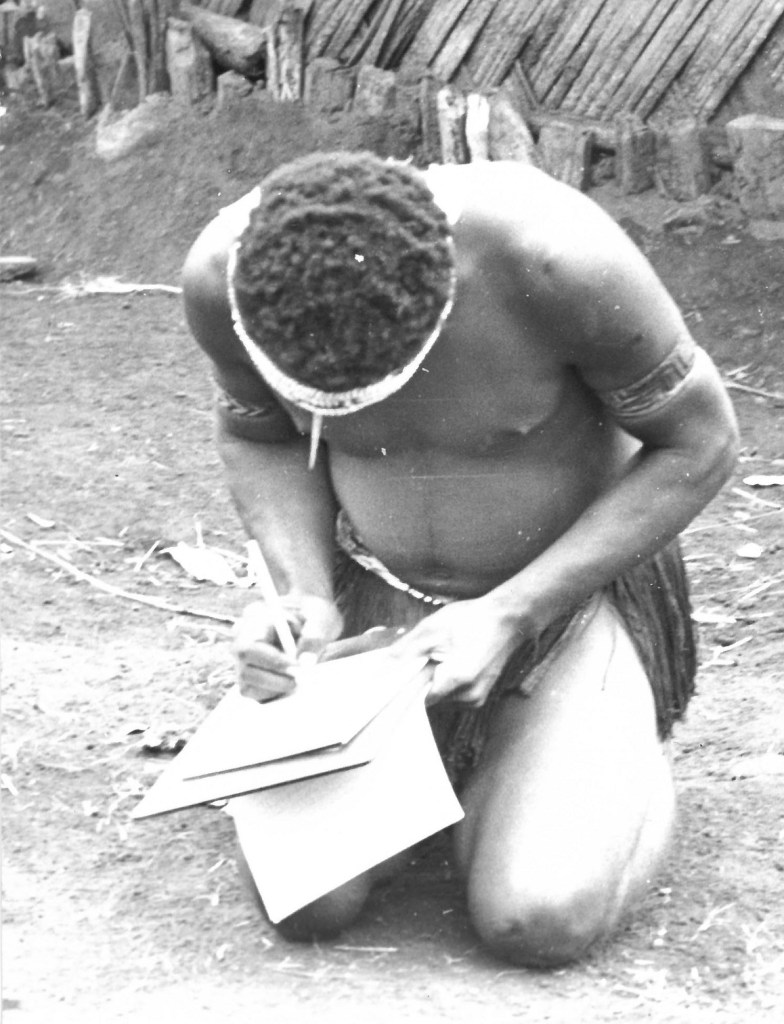

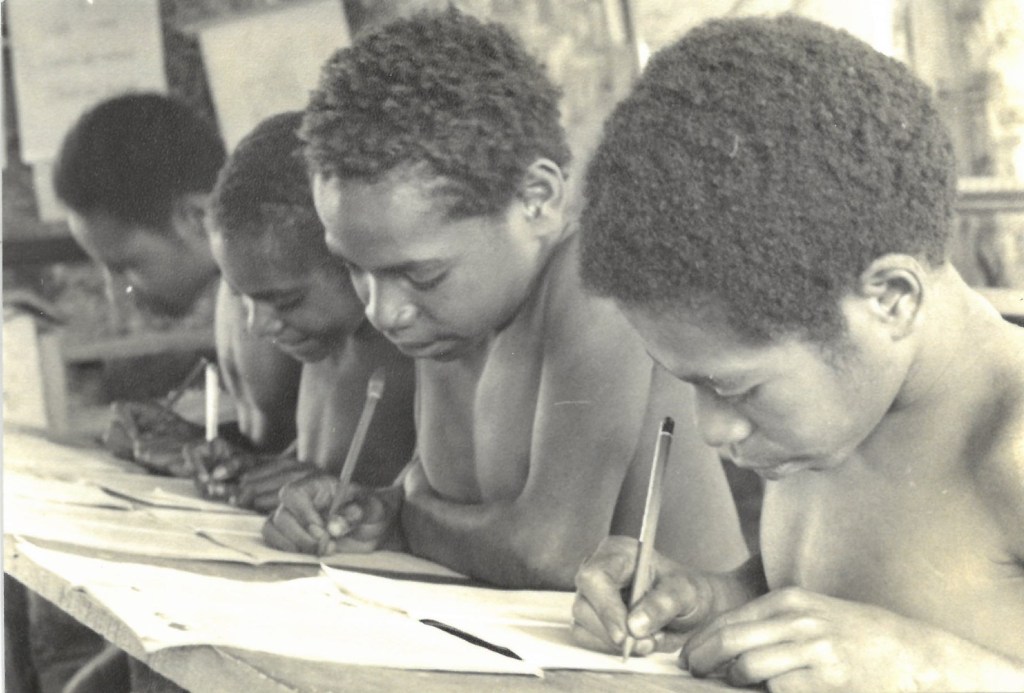

After completing the SIL course and additional biblical studies at Asbury Theological Seminary in 1963, Vida traveled to Papua New Guinea the following year, where she met her new Wycliffe partner, Dr. Darlene Bee. Since 1958, Bee had been working on translating the Usarufa language, spoken by 800 to 900 people in the country’s eastern highlands. Although language and literacy work formed the core of Vida’s time with the Usarufa, music was never far from her thoughts. Immersed in the Usarufa’s distinctive musical culture, she began to explore how the long Christian tradition of praise and worship could be translated in way that preserved and encouraged indigenous musical systems.

Supported by Darlene Bee and Wycliffe, Vida entered a doctoral program for ethnomusicology at the University of New Zealand, earning a first for her work developing a method of analyzing music that allowed an outsider to compose idiomatically within an indigenous music system.

Tragically, in 1972, Darlene Bee died in a plane crash. Although Vida remained in New Zealand to finish her doctoral program, she continued the work on the Usarufa New Testament through correspondence with Usarufa partners in New Guinea. After 23 years of effort, the Usarufa New Testament was finally completed. In 1981, Vida returned to the remote village for the first time since Bee’s funeral to personally deliver the newly printed Bibles.

In the summer of 1975, while teaching a course on the music of Papua New Guinea at Chicago Musical College, Vida caught the attention of Dr. Harold Best, then Dean of the Wheaton College Conservatory. He invited her to serve as a special instructor in ethnomusicology for the fall term at Wheaton. By 1979, their collaboration led to the creation of a new major in Ethnomusicology and Linguistics.

Across her near two decades as a professor at Wheaton, Dr. Chenoweth and her ethnomusicology students visited New Guinea, Indonesia, Kenya, the Solomon Islands, and South America, analyzing more than 34 different tribal music systems. Many of the field recordings from these Wheaton trips are held in the Chenoweth Paper’s audio files. Vida retired from the Conservatory in 1993 and returned to Oklahoma, where she focused on organizing and documenting her collection of over 900 field recordings for inclusion in the Archive of Folk Culture at the Library of Congress.

Vida Chenoweth’s career as a concert marimbist was also honored in 1994 when she was inducted into the Percussive Arts Society Hall of Fame. She passed away in December 2018, shortly after celebrating her 90th birthday.

Additional photographs, clippings, ethnomusicology and linguistic research, field dairies, correspondence, and audio recordings documenting the life and work of Vida Chenoweth are available for research at Wheaton Archives & Special Collections. To explore the collection, review the finding aid at SC-114: Papers of Vida Chenoweth.