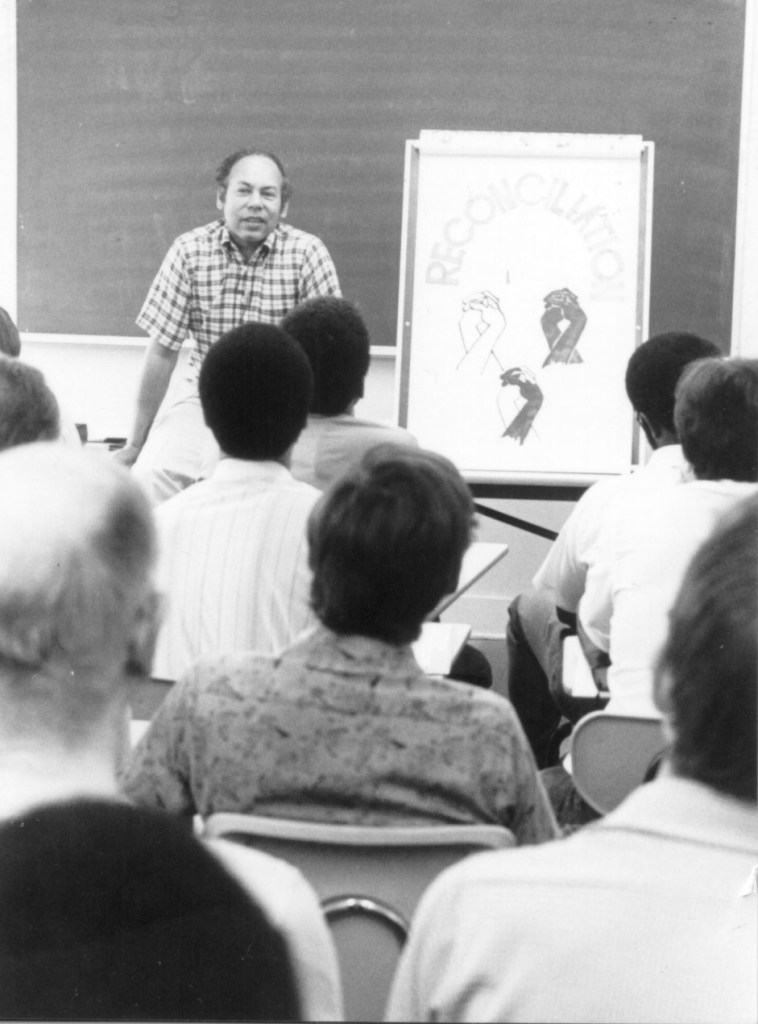

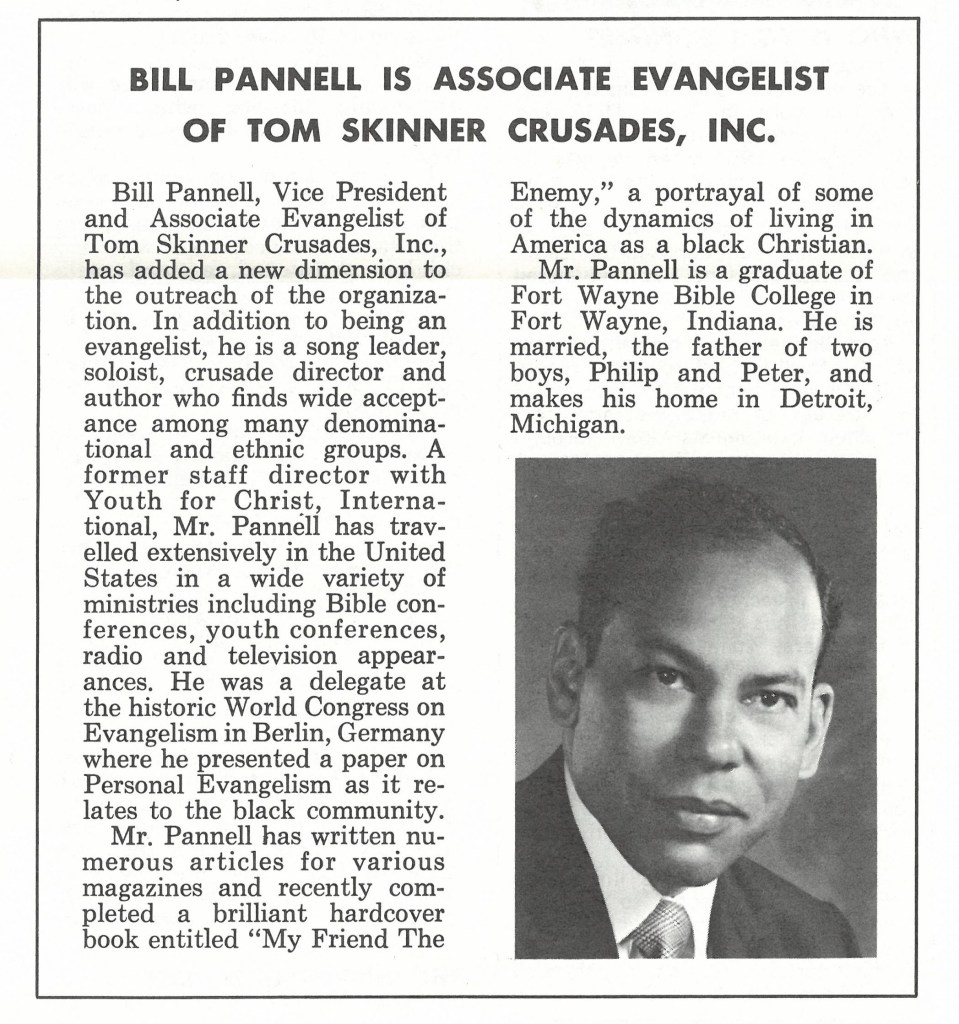

In celebration of Black History Month this February, Wheaton Archives & Special Collections features our oral history collection with Rev. Dr. William E. Pannell, who passed away last October. Over more than five decades of ministry, Dr. Pannell served as a youth pastor in Detroit, directed training for Youth for Christ, helped lead Tom Skinner Associates as Vice President, and taught future generations of pastors and evangelists at Fuller Theological Seminary as the assistant professor of evangelism and director of the Black Pastors’ program. Along with his busy work as an evangelist and teacher, Dr. Pannell published several influential books on race and the evangelical church, including My Friend, the Enemy (1968), Evangelism from the Bottom Up (1992), and The Coming Race Wars?: A Cry for Reconciliation (1993).

From 1995 to 2007, Wheaton archivist Bob Shuster sat down with Dr. Pannell for several sessions of oral history interviews. Totaling more than seven hours, the recordings include Dr. Pannell’s reflections on his childhood, education, Christian faith, ministry development, and race relations in the American church. Wheaton Archives & Special Collections recently released the complete transcripts to these interviews, which are now available through the online guide to Collection 498: William E. Pannell Oral History Interviews. Below are selections from the interviews covering Dr. Pannell’s early life, growing racial consciousness, visit to the 1966 Congress on Evangelism, and development of his work with B.M. Nottage and Tom Skinner. The selections have been edited for clarity and brevity.

Oral History Interview with William Pannell, May 25, 1995 (CN498, Tape T01):

SHUSTER: You mentioned in your book My Friend, the Enemy, that the standard of the White community was never really challenged in your mind when you were growing up. What do you mean by that?

PANNELL: I think, Bob, the social conditioning that…to which we were all exposed, Black and White, was…was the same. That is to say, the fundamental assumption was what the…what the Black community always called “the rightness of whiteness ideology.” It’s the ideology of White supremacy. In the South that took on a very blatant and ugly face. In the North in the little town, I was raised there…there was…I saw no ugliness whatsoever, especially in my younger years. It was Dick and Jane and their integrated dog Spot. It was the Lone Ranger and Tonto. It was all of that stuff. It was….in other words, we were all conditioned to be a nation, a culture, a generation of believers, and we believed in the system, the culture, the country, and all of its institutions. The problem with that, of course, that…is that we were all victims…. It was… education as propaganda in some important ways. It made us good citizens, in a way, but it didn’t allow the kinds of questions to surface that would have unpacked the reality of that other America which later on was…was exposed in the ‘60s. But be that as it may, my growing-up days, I kind of…now I look back on them, I kind of liken them to our kind of Northern, small town, scrubbed version of Huck Finn-house-with-the-picket-fence kind of world.

SHUSTER: But you were aware of it?

PANNELL: I was made aware of it also when I went to the country club to caddy. I doubt very much if Black people were allowed to be members of that club, but I caddied there, and I caddied for some of the fathers of the town. But caddies were Black and White. My friends caddied…we all caddied together because we all played together. We played ball together, we fished together, we had a great time together, so we didn’t …race didn’t impinge upon our appreciation for one another or our comradery. But it was fairly clear that the town, like most towns, was clearly divided along race and class lines, class perhaps more than race. So of course, the Episcopalians and the Presbyterians had memberships at the club, a few Methodists, and for the rest, you know, it was kind of downhill from there, in a way. And…so that…that was fairly obvious. And it was also fairly obvious that as far as the town fathers were concerned, certain kids would run the town, and certain kids would work for them…. We didn’t have names for that, [laughs] and we didn’t talk about it, and nobody pointed it out in the Sociology class, or anything of the sort, but it…it was there.

Oral History Interview with William Pannell, April 21, 1998 (CN498, Tape T03):

SHUSTER: Can you think of some of the ways [B.M. Nottage] influenced you? In particular, do you see definite parts of your ministry that would have been different if you had never known him?

PANNELL: Probably. Nottage introduced me to grace. He became my theological mentor at that point. Up to that time, I had come out of a Holiness Fundamentalism, which believed in grace but didn’t know how to think about it, experience it in any liberating sort of way. Afraid that if you took grace seriously, you might really end up believing in security. Have mercy, what a terrible word. Nottage did not introduce me to any eternal security. He introduced me to the God who saves by grace, and who, having saved one by grace, disciplines one by grace as well. It’s a grace-filled existence, wave upon wave upon wave…you know, grace keeps coming at you, through Jesus Christ. And that’s an incredible thing. Took me a while to comprehend it. I just…it was overwhelming. As was all of the stuff that he shared with me.

I lived with him and his wife for a couple of years before I was married. Whenever I would return to Detroit from revival meetings or my own preaching or whatever I was doing, I would head for their house. Their house became my home. And we would have Ephesians and Colossians for breakfast, devotions at lunch and dinner and before bedtime snack. It was astonishing. And by the way…I don’t think there’s a better method yet devised for the training of young men for ministry. You can send them to seminary, you know, or the more radical way would be to invite them into the home of a pastor/theologian. And there, mentor them…. I learned from Nottage that it was indeed possible to have a marriage of over forty years and still be passionately in love. Ah boy, that was…that was something. For a young man who was beginning to suspect that he’d like to be married someday and not seeing a whole lot of attractive models out there of people who were still passionate about this thing after a lot of years, that was…that was a fabulous sort of thing. If I were to say, “What makes you tick like this?” You know, you’d get a different story from Mrs. Nottage than you would from him in a way ‘cause she knew him. She loved him and…but she knew him. And so that’s something I hadn’t yet gotten into.

Theologically though, he would always say that he tried very hard to relate to his wife as Christ loved the Church and give Himself up for her. That was his starting point. And that became mine as well. In other words, everything that he was and practiced seemed to be based on some biblical insight or injunction. To live the Scriptures was his passion, to please the Lord and so forth. So…so I saw it as it affected his marriage. I watched him relate to Christians. He said at one point…he said, “Bill, you’re always safe when you relate to another man’s bride in a respectful manner.” That comment came about as a corrective to some criticism that I was leveling against the Church or Christians in some church or something. “I have learned,” he said, [laughs] “that you’re always safe and usually responsible when you relate to another man’s bride.” It’s interesting. He was talking about the bride of Christ!

SHUSTER: And so, in other words he was saying you need to be very respectful when you criticize a congregation?

PANNELL: Very careful. Because they don’t belong to you. They are members of the Body of Christ, the Bride of Christ. And it’s His responsibility, not yours. Only He can criticize her. And He loves her, gave Himself up for her. And he’s basically saying, “If you really want the grounds to be critical, first check out the extent to which or the depth of your love for her. If you have and are willing to give yourself up for her, then you have earned the right to criticize her. Until then, back off.” All of that was…was there in that bit of counsel and advice. And I watched him practice that. Very reticent to criticize God’s people. [Laughs] Very remarkable.

SHUSTER: So, you were at this point struggling with how, in America, race and Christianity combined? Or how…how the church should express itself?

PANNELL: More of the latter. I…I wasn’t so much involved in the…I really wasn’t aware of the emerging civil rights struggle. I really wasn’t up on that. I was concerned mainly with the integrity of the church. And I knew that the church that I was exposed to was composed of Black people and white people and hardly ever did the twain meet, at an occasional Bible conference or something of that sort. Nottage…. and I got into that in a deeper sort of way…the cruciality of the integrity of the church by being a part of Nottage’s life. We ate together and traveled together and laughed together and cried together and preached and all that…all that good stuff. And I learned a ton. We would never have a conference in Detroit in the Black assemblies without the platform being integrated, whether it be a Bible conference, a missions conference, I didn’t care what it was. We tried to do that. When I assumed leadership of the youth conference, we did the same thing. We did that theologically, we intentionally made sure that that platform, that ministry was a shared ministry because we felt that’s the nature of the Church.

It became increasingly difficult to follow through on that up through the ‘50s and ‘60s because more and more of our white friends absented themselves from the city. They kept moving farther and farther away. It became increasingly difficult to even find them. And it affected not…I don’t know that it affected Mr. Nottage quite so much because he was a…right now, getting older and more and more infirm. But those us of who followed in his train, who had emerged as leaders in the [Brethren] assemblies found that we were less and less interested in chasing after these white folks. They obviously didn’t want to live with us. They obviously did not intend that we be a part of their life, even a part of their assembly life. They were as segregated and as racist as any other group that we…that we were aware…. We were greatly disappointed in them. Only occasionally did some of them visit our Bible conferences, but it was a totally different atmosphere.

One of the…an interesting story that illustrates this. I had joined Tom Skinner’s evangelistic association, helped shape a new thing with Tom… in the spring of 1968. And the condition that I had described, an increasing distance between white assemblies and Black assemblies in the Detroit area was very, by now, very fixed, very pronounced. And Tom had come to the city and was preaching out in the suburbs someplace and I went out to join him. After the service, a young white kid came up to me and expressed an awareness of who I was. He said, “You’re Bill Pannell, aren’t you?” And I said, “Yes. How do you know?” And he said, “Well, I recognize you from the back of your book.” And I said, “Okay.” He said, “You’re…you’re part of the assemblies here, aren’t you?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “I…my name is Jim Wallis and I…I’m also part of the assemblies but I…I’m not happy with the fact that you are in the city and you’re Black and we’re in the suburbs and we’re white and we don’t…we don’t fellowship. Why is that and what can we do about it?” That was the beginning of what has become now a lifelong relationship with Jim. Jim’s disenchantment with the Brethren movement and that brand of Christianity had already begun. And it began, I think, or at least was exacerbated by what he judged to be un-Christian and racist remarks among the assembly people. He said, “Pannell, you were long ago…we…I knew of you by reputation and I knew they would never invite you to our meetings in the suburbs. They considered you to be a radical.” You see, by then there had developed a perception of myself at least, who had once been the fair-haired heir apparent to Mr. Nottage that I was a radical. Something had happened to me. And they probably had concluded that it’s not…it wasn’t because of any teaching or mentoring that I’d gotten from Mr. Nottage. “Something has happened to Pannell,” type of thing. “He’s not any longer safe.” Which was true, [laughs] in a way. I was not…I…. That would be an interesting thing to talk about some time.

SHUSTER: Do you think you had changed?

PANNELL: Oh sure. And I…but I’m not so sure how it happened. I’ll have to talk about that sometime. It’s important because it happened, I think, because I had been exposed in the course of my itinerant ministries now to people who were much more in touch with what was going on in the culture than I was. I think, for instance, of…of a friend and brother by the name of Vern Miller who and his wife, Helen, whites, had ploughed themselves in the Black community around Huff Avenue in Cleveland and later on in Lee Heights. And had spent a career along with another network of white Mennonites who had come out of Goshen, out of the Mennonite system, ploughed themselves into our urban centers, invited me to be their evangelist and so forth. And I got involved there and I began to see the world through Mennonite eyes, which is a whole ‘nother ball game in terms of how one relates to the culture than I’d ever been exposed to in the Brethren movement or ever would have been. So the whole new thing began to happen in my life and my perspectives on culture and whatever. It was through…I think it was Vern who first exposed me to the radical significance of a young preacher from Atlanta by the name of Martin Luther King, Jr. So by 1968, I was quite down the road from where I had left off with Mr. Nottage.

SHUSTER: But you’d heard of Martin Luther King before 1968?

PANNELL: Oh, I think…yes, surely. But I had not really assessed his significance. I was…. But in ’68, I met this young Jim Wallis who was actually in…in concrete ways, but symbolically also, another part of what was going on at the edges of these established expressions of Christian faith. I had moved more than I knew from where I had been as the mentee of Nottage. Jim had moved more than he knew from where he had been at there too. Three years later, Jim Wallis was deeply involved as a leader of the student radical movement at Michigan State. The next time I saw him, he was bearded and was studying, trying to find a new hermeneutic for life and ministry, but studying at Trinity Seminary and I was a guest lecturer. I was with Skinner and so forth and so on. This is the late end…this is the tail end of the ‘60s, very early ‘70s. Jim and his cohorts were just cranking out the Post American. They’d take me to the airport after class at Trinity and we’d have a blast. And it was a very wonderful network of relationships. But by now I had moved significantly from the more rigid framework of…of hermeneutics and so forth associated with the Brethren movement.

Oral History Interview with William Pannell, February 28, 2000 (CN498, Tape T04):

SHUSTER: You mentioned being at the 1966 World Congress on Evangelism…. What stands out in your memory from that meeting?

PANNELL: Well, I was very impressed with that. In the first place, I was quite delighted to have…to have been invited.

SHUSTER: How did that come about?

PANNELL: I’m not sure, but I…I remember probably a conversation with Carl Henry…. a very creative, seminal thinker, a strategist. And we met somewhere, [laughs] I don’t…I don’t remember. In all of this, I am deeply remorseful for not keeping a journal. It would have been a very rich…but I just didn’t think about that, didn’t think of myself more seriously. But Carl had asked me, would I write? Would I do some writing? And I’m not sure whether it was for Christianity Today, but I think it was. I believe it was, and I wrote that piece. He said, “Well, what would you think about doing a piece that x-thousands of people would read.” So, I…I wrote something…. Subsequent to that I received an invitation from him to participate in the Congress on Evangelism that was projected for…for Germany, and that was then followed up with a request to present a paper for that. And so, I agreed to do that. I was quite pleased, honored to be considered, really. And it was completely out of the blue as far as I was concerned. But anyhow I was invited, I did the paper and went to the congress. And it was a…kind [laughs] of a major thing for me. I’d never traveled abroad, at least in that direction. I’d been in the Caribbean, but I’d…so, this was…this was nice. And it was an awe-inspiring sort of thing to be in the company with all these Evangelical leaders, whose stuff I had read and whose sermons I had heard and…and whose reputations I had known about from their interest, involvement in missions and missiology and evangelistic enterprise and…and…and so forth.

It was there that I first sat next to Bill Bright, for instance, or I think Charles E. Fuller was still living at the time, and I think he was there, not very, very active, but I think…I think he was there. The late Paul Stromberg Rees, who more than any other man, was something of a mentor of mine. I liked the way Paul…I liked the way his mind worked, and I loved his preaching.…I regularly read his column, which was on the back page of the new World Vision Magazine. For me, he was the only one that was making any sense to me in that magazine. But that’s bias, in a way, because in other words he was just scratching where I was itching. But he talked about pastors’ conferences abroad and a number of other things. And I had thought that one of the things that we needed domestically in the Black community was a series of those kinds of conferences for pastors. And so, I initiated some…either some correspondence or some conversation, some conference place. And one of the nice things about Paul was he always treated me as if I was worthy of listening to. He would give me his undivided attention, whether it was three minutes or whatever. He was…he was most respectful of that. And we really clicked in Berlin because it didn’t take me long to realize that for all of the worth of that congress, it wasn’t really dealing with the total agenda. As you’ll remember, the theme of that conference in three categories: One World, One Gospel, One something or other. They were dealing with One Gospel and One Task, but they weren’t dealing with the world.

SHUSTER: How do you mean that?

PANNELL: The need of the world was to be saved, hence the need to understand the gospel and to proclaim it. But their understanding of the world and their discussion about the world was very…was almost nil and very superficial. And…and for that reason their understanding of the gospel, I think, was simplistic and their understanding of the mission was simplistic in that it lacked a social ethic. It lacked…it lacked a theology of social ethics. It lacked an appropriate exegetical work on the nature of the human condition as affected by systems, political, economic, and so forth… I wasn’t very happy with it, and so, I sought out my friend Paul Rees. And Paul confirmed, at least, that he was disturbed about the same thing. And he said, “Bill, I don’t know much about what…what can be done about that.” He said, “I don’t really have any clout.” But he said, “I will…I promise you; I will speak about it in the committee meeting,” because he was a part of that inner network. And I don’t have the slightest doubt but that he did because he was then given maybe five minutes to talk about it, or something like that, to mention it or something. It was very skimpy. I’d have to look at the agenda again….

It was an important meeting because it exposed me to the broader international fellowship of Evangelicals. I met Hans Burki there who was…who was at the time the director of International Fellowship of Evangelical Students…. I had an opportunity to meet Frank Laubach…. I fell in line…fell in step with him one day coming out of a discussion on…on ethics, I think, morality and ethics or something, I’m not so sure. And I said, “Mr. Laubach, how’s it going?” And he said, “Well, I…they’re not even close.” I said, “Well, what are they talking about?” I knew they were talking about ethics and morality and those sorts of things. And I said, “Well, sir, what do you consider the most pressing moral issue in our time.” “Oh,” he said, “it’s obvious.” He said, “The most pressing moral question of our time is when it is right to kill a man. When…when the government says so? When…when the Republicans? Or the Democrats? Or…when is right to kill a man?” And he was talking about over against the…the emerging tragedy of Vietnam among other things. We had a fabulous conversation. Berlin for me was something like that.

Oral History Interview with William Pannell, August 18, 2003 (CN498, Tape T07):

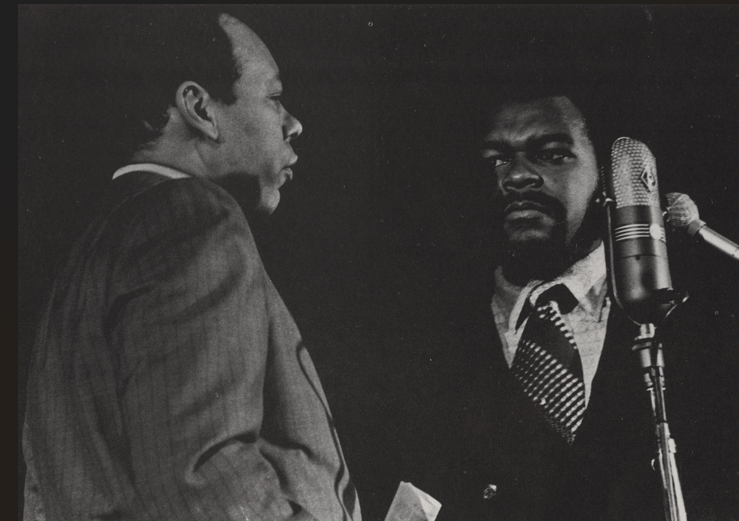

SHUSTER: Can you give a summary or description of what the influence of Tom Skinner Associates was? I mean, what difference did Tom Skinner Associates make? How did it change things?

PANNELL: Well, it caught the imagination of a new generation of young Blacks, for one thing, who…I remember talking to one guy who is now a professor at a major college, who said, “At any one time, if you guys had ever crooked your little finger, us guys would have jumped through a wall to get there. You were the…the organization as far as we…we were concerned. The only Christian organization we knew of that had the strength and the visibility and…and that seemed to have the ideas. We were all jazzed about that.” For instance, one way to gauge that would be to reflect on the influence of our organization at the Urbana gathering of InterVarsity 1970. We virtually had a convention within the convention. And most of the guys that helped set that thing up were…either belonged to our organization or were powerfully influenced by us in direct relationship with one another. Skinner, of course, was the headliner of that, but…but when…quite apart from his platform work, the famous speech of the day, “The Liberator Has Come,” we could talk about the significance of that sermon title and that particular sermon because it represents, I think, the full flowering of ideas that had their genesis in the 1968 Newark meetings and those ideas associated with identity, and community, and power.

SHUSTER: Do you recall what the background was for that speech?

PANNELL: The background for this, of course, was the Civil Rights struggle. The background for that was the Civil Rights struggle and the ill-ease or the dis-ease in Evangelical organizations with the fact that they were lily White and that…and that the whole missionary emphasis of InterVarsity was overseas. Uneasiness even in some missionary circles like that, that there weren’t any Black missionaries, there weren’t any…there was no…very little interest. I’d had conversations over the years, with some of those execs from Wycliffe Translators to whoever and they were always…always the same litany, the same conversation about, “Where are Blacks. Are there any Blacks who would be interested?” InterVarsity in that regard was not any different from any of the rest of them in terms of their lack of involved African Americans on staff. There were a few more people on staff, of course, but we…what they decided to do was to really go after young African American college students for that conference, more so than at any time. And so, what they did was they pulled together a number of young African American students from various campuses, made a film, which was a recruitment device to get…and they interviewed these students and…and they asked fairly important kinds of questions. “Why in the world would an African American be interested in coming to a conference of that sort? After all, as far as we’re concerned, and given the…the current history of…of urban reality that we’re associated with, the mission field for us is just down the street, just around the corner, for crying out loud. Over there on that vacant lot. So, why in the world….?” You know, okay. And an unwillingness to buy into what, by now in the minds of a lot of those young people, had been an expression of White Christian manifest destiny. “To the regions beyond” and all of that stuff that we sang about so vociferously in our meetings in Bible colleges and all of that jazz. For some of us, even the term missionary had become a problem. And so, if you’re going to come into our communities, try…try very hard to get beyond that term was…was some of the stuff I was beginning to say. Didn’t meet with any warm reception, but there it was.

And so, so, if you take the Civil Rights movement, a growing awareness on the part of younger African American college students who really wanted to follow Jesus but who were beginning to wrestle with Christology. “Who is this Jesus? What kind of a Jesus is this? What is the relationship of this Jesus to the burgeoning motifs of liberation throughout the world?” The most prominent, of course, being so-called Latin liberation movements, Latin theology, Liberation Theology, those motifs. And by then, you could get theologies in Red, White, and Yellow anywhere in the world. You could get water buffalo theology; you could get all kinds of theologies of having to do with perceived and actual oppression. Theology from below, if you will. That was…all that stuff was very much in the air, and it had powerfully…began to effect young people. It was not an unusual thing to say, for instance, to be on a Black college campus and to be asked by Black students, “What does Jesus have to do with the revolution? What kind of Jesus…? Did Billy Graham send you guys?” Or…all kinds of questions that reflected a growing awareness that the times had changed, and that if Jesus was to speak to that reality, radical social change, or at least the desire for radical social change he would have to be a different Jesus, maybe even than the one Graham was talking about and so forth. As an organization, and most particularly in conversations with our core team—that would be Tom and myself, Carl Ellis, and some of the young turks who were in campus ministry—we…we knew that we…that the apologetic, say, of a Francis Schaeffer wasn’t where we were either. We weren’t…we hadn’t found it. We weren’t satisfied. We hadn’t found it, but we were convinced that the Jesus that we were hooked into had to speak with some relevance to the issue of freedom and liberation. I had begun to work with the motif of the Kingdom of God. We couldn’t find any follow-up material that would reflect that. Most of it were variations on the Four Laws or…or something of that sort, which we thought was superficial.

And so, we began to work on…on…on this motif of the Kingdom, because we wanted a biblical idea that was so fundamental and so powerful that you could with integrity preach it and…and argue it, for it, and capture the felt needs of people across the broad spectrum of human need. Okay. Which meant, of course, that for Tom and I, we had to get beyond Plymouth Brethren captivity to J.N. Darby and…and dispensationalism. Of course. And we were criticized by representatives of that group from time to time wherever we would meet them, whether they were laypeople or whatever for having departed in some ways from the Gospel because of our Kingdom emphasis. And it was that Kingdom emphasis, that got us into trouble with a number of members of the Evangelical community, Christian radio, and so forth. They began to say, “Skinner has become too radical and Pannell has corrupted him” [laughs].

Explore all the recordings and transcripts for the interview series on the online guide to Collection 498: William E. Pannell Oral History Interviews.

In addition to Collection 498, several collections at Wheaton Archives & Special Collections hold further correspondence, newsletters, photographs, and recordings illustrating Dr. Pannell’s work and influence as a church leader and social commentator. These include Collection 430: Tom Skinner Papers, Collection 300: InterVarsity Christian Fellowship Records, Collection SC 113: Records of the National Association of Evangelicals, Collection 548: Atlanta ’88 Congress on Evangelizing Black America Records, and Collection 538: National Summits on Black Church Development Records, as well as oral history interviews with Beverly Pannell Yates and Michael T. Flowers. More documents covering Dr. Pannell’s life and ministry are also available online through Fuller Library’s William E. Pannell Collection.