This month, Wheaton Archives & Special Collections features a post from long-time Wheaton archivist, Paul Ericksen. Since joining the then Billy Graham Center Archives in 1982, Paul has interviewed more than 125 individuals and processed and transcribed dozens of oral history interviews with missionaries, evangelists, and Christian leaders.

Archivists are primarily skilled facilitators as they focus on gathering, arranging and describing primary source materials, and assisting researchers in using their collections. Through archival “finding aids,” archivists help create the intricate web of descriptions, subject headings, and box lists that guide a researcher to identify which collections will contain relevant documents for their study, and in which boxes or folders they will find these documents. While gathering existing historical documents and preparing them for optimal access and use by researchers forms the core of archival work, archivists also collaborate to create historical documents through oral history interviews. An oral record of a person’s life and career, these interviews offer a stimulating window into the unique narratives and experiences of individuals.

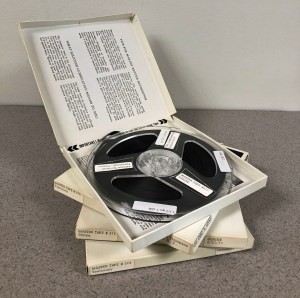

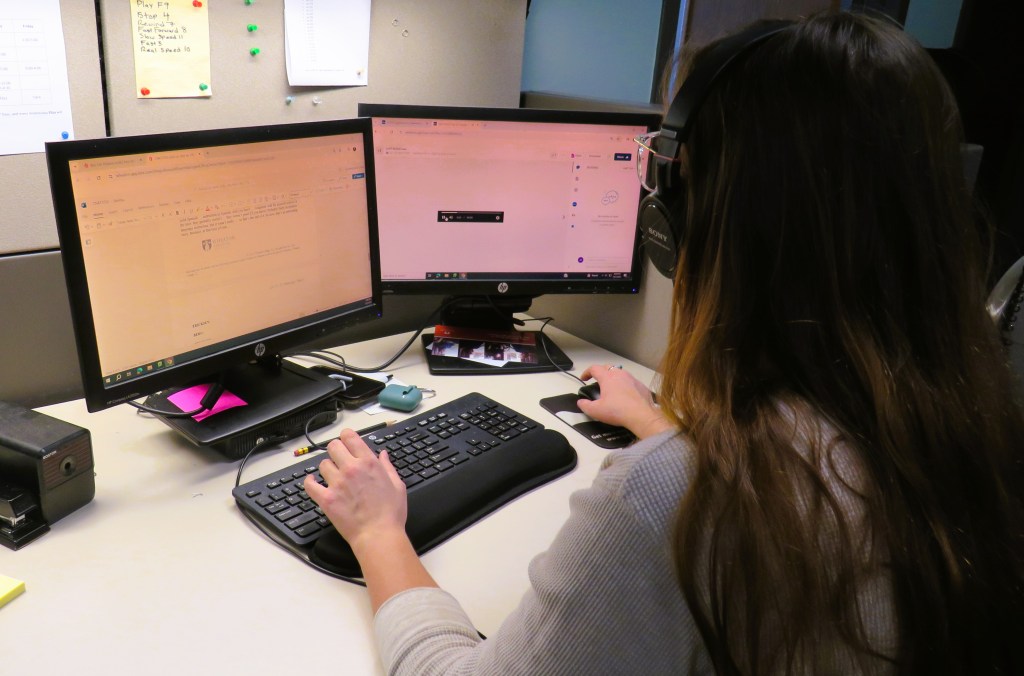

Over the course of the almost fifty years since the Billy Graham Center Archives (now the Evangelism and Missions Archives) was formed in 1975, its archivists have continuously managed an informal oral history program to further enrich its resources on global evangelism. Archivists have interviewed more than 370 individuals, compiling over 1,200 hours of sound recordings on analog reels, cassette tapes, and as digital files. Through further transcription of recordings, researchers also gain the benefit of reading or searching the full-text accounts for information on a topic, person, or location. One of the earliest of these interviews was with Andrew Wyzenbeek about his memories of Billy Sunday meetings at the turn of the century. Most recently, a few current Billy Graham Scholarship recipients were interviewed in the past year about their experience and ministry in several Asian countries.

These interviews cover the Archives’ major collecting themes of evangelism and missions, but they also document the many associated topics that reflect the careers and other activities of missionaries and evangelists, such as the political upheavals in African countries during independence movements, relationship dynamics and conflict between missionaries, and strategies for communicating the gospel in culturally adapted ways. The geographic scope of the interviews span from the United States to most countries of the world – from Liberia to Jordan to Afghanistan to Costa Rica. The oral histories also capture observations about the cultural, social, historical, and religious aspects of those countries and their citizens.

Many interviews in the Evangelism & Missions Archives are with retired missionaries looking back on their careers. But our interview collections also include those with international scholarship recipients at Wheaton College, who help record the stories of the global church and the spread of the gospel from a non-Western perspective. The Archives also collect oral histories done by organizational or independent interviewers. Ned Hale, for example, on behalf of his InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, has conducted or coordinated interviews with more than one hundred IVCF leaders and staff that were donated to the Archives.

These interviews are never a formulaic process. They are rarely predictable – each interview bringing its own challenges of logistics and personality. Moreover, oral historians rarely get to ask all the questions they bring to a session, but interviewees’ responses almost always surface valuable memories and unanticipated areas to explore further.

So, how does an archivist go about preparing for an oral history that will: 1) help the interviewee tell their own story, 2) anticipate the needs on behalf of future researchers as a basis for questions, and 3) make use of tangents and rabbit trails that will be interesting and productive?

To guide an interviewee through the narrative of their life, activity, influences, and contributions, the oral historian wants to know as much as possible beforehand about the person’s chronology and career, the communities or countries where they worked, and the major events that they were observers of. They want to familiarize themselves with events that took place around them, whether religious, political or social movements, natural disasters, or significant people groups they had contact with.

Sometimes there are topics that surface that are sensitive and may require a restriction being placed on access for a period to respect the privacy of the interviewee or a person being discussed. We always attempt to record this with the accepted limitation that withholding access for a relatively short period of time is preferable to excluding it entirely from the interview, which results in an incomplete story for the long historical record.

Let me use my interviews with Leighton Ford last year as case study of how this works.

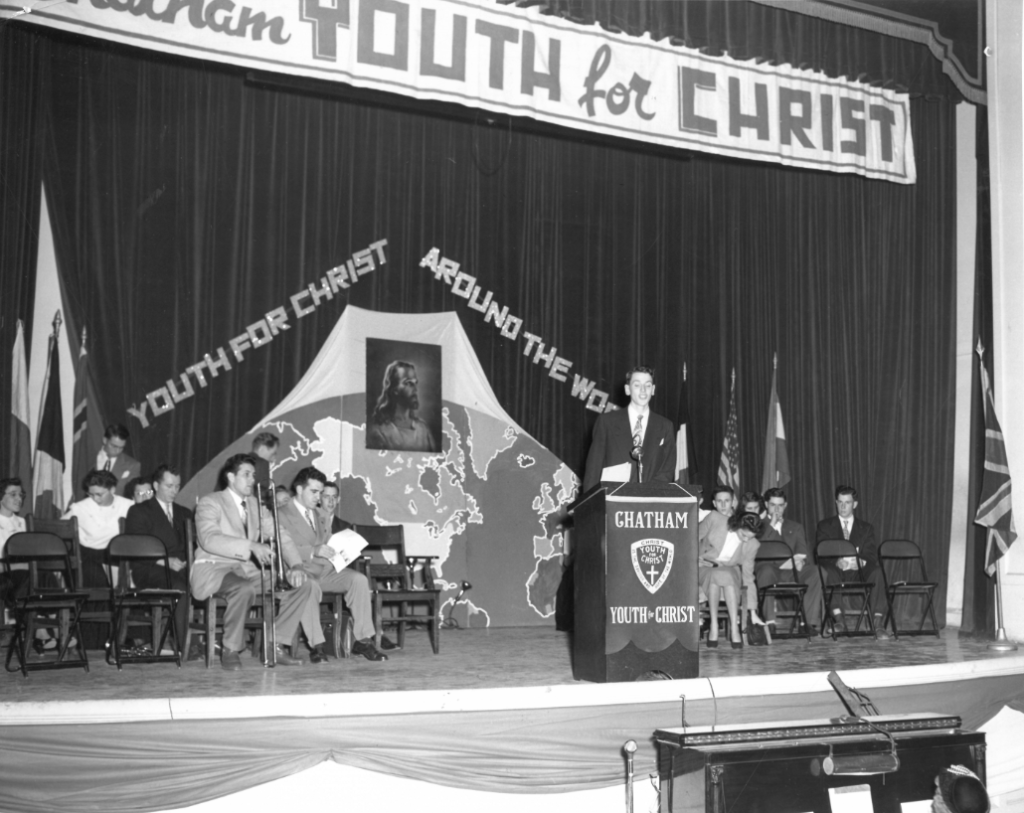

Ford’s long career as an evangelist, leadership mentor, and participant in global Evangelical organizations provides a broad canvas to capture in oral histories. Beginning with his timeline, I developed questions about his childhood in Canada, being raised by a single mother, leading a Youth for Christ group in Chatham, Ontario, education at Wheaton College and his classmates, meeting Billy Graham, whose sister Jean, also a Wheaton student, would become Ford’s wife.

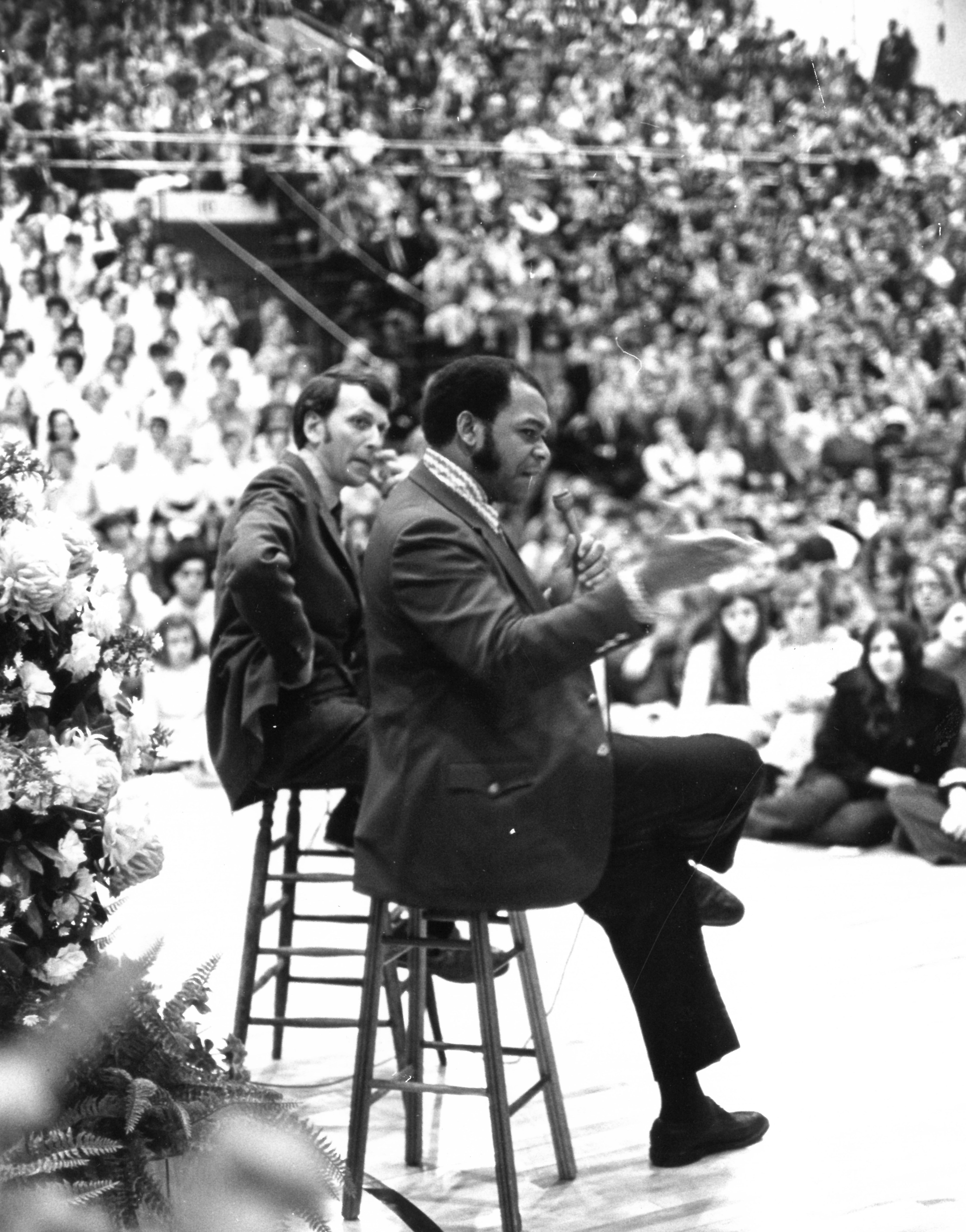

My questions about his evangelistic career after graduating from Wheaton and completing his seminary education at Columbia Theological Seminary centered on his joining his brother-in-law’s Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, his own evangelistic events and other contributions to the BGEA, especially the Billy Graham’s 1957 New York Crusade, and many colleagues in the organization. (There are always subjects left uncovered at the end of an interview. A major one in Ford’s case was his founding Leighton Ford Ministries in 1986 when he was no longer officially associated with the BGEA. This subject remains for a subsequent interview.)

Another major area I asked Ford about was his leadership of the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization from 1973-1992, from preparing for the 1974 Lausanne Congress to its follow-up global events in 1980 and 1989 and numerous specialized consultations. I also added to the mix my questions about his family, his wife’s Graham family, their children, and his avocation as a painter.

Because Ford has written several books, I targeted my questions to areas not covered in these published works. The purpose of my interviews was to get Ford’s firsthand account by guiding him to tell his own story. My rule of thumb with Ford, as with the many others I and the other archivists have interviewed, is to avoid asking questions that could be answered with a simple “yes” or “no.” Our approach is instead to guide the interviewee past generalized or vague answers to give concrete examples of events, relationships, and personal character, and avoid opinions.

The result of my Ford interviews was 239 minutes of recordings broken down into three sessions in May 2023 at the Fords’ residence in Charlotte, NC. As an example, the resulting description, already available in the Archives’ database and available online in its entirety, summarizes the topics covered in the first session:

T1. May 15, 2023. Digital recording, 94 minutes, 0.474 GB, WAV format, recorded at Ford’s residence in Charlotte, NC, with dog Buddy sleeping at Ford’s feet. Topics covered include his early life, adoption, spiritual influences, impressions of Oswald Smith preaching on prayer at a summer camp, role in launching Youth for Christ chapter in his hometown, education and experience at Wheaton College (graduated 1952), part in a gospel team, Philosophy major and professors, 1950 revival, fellow students Norm Rohrer, John Wesley White, Frank Nelson, and Peter Deyneka, Jr., meeting and dating Jean Graham, theological education at Columbia Theological Seminary in Atlanta, course of study, professor Manfred Gutzke, marriage, Billy Graham Evangelistic Association figures, including Billy Graham, George Wilson, T.W. Wilson, Grady Wilson, Walter Smyth, Sterling Huston, John Corts, and George Beverly Shea, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., at the 1957 New York Crusade, and Ford’s assistance to Graham in the 1955 Toronto Crusade.

No interview is without its surprises and unique memorable qualities. Each of Ford’s interview sessions featured his dog Buddy sleeping soundly through my questions and Ford’s commentary – no disruption, just his comfortable presence.

While valuable resources, oral histories have their limitations. They are a person’s memories, which can change over time, reflect their own biases or present interpretations of past events, or have similar gaps as other documents with details overlooked or not remembered. The interviewee also has the capacity to self-censor, which may diminish the extent or value of a story. Or they may go on and on, in effect hiding the golden nugget of a memory under the weight of seemingly irrelevant details. But in preserving these personal stories, as well as the original inflection, pace, tone of voice, or the pause that may carry emotion, oral histories add rich first-hand resources to the collections available to researchers.

A few last guidelines from many years of experience – Some oral history scenarios are best avoided for recording a quality interview: 1) Do not ask run-on questions or nest multiple questions inside a question; 2) do not record an oral history with more than one person at a time, especially a spouse who needs to correct the interviewee along the way or interject their own thoughts; and 3) never record an interview while driving the interviewee to a destination. I have memorably done each of these three and have learned from my mistakes.

One of the rich benefits of conducting oral histories is getting to know the interviewee – finding out what makes them tick, what motivates them, how they have uniquely seen and interacted with the world. Although research utility may vary, each interviewee’s story is valuable and interesting for their individual testimony and the wide variety of subjects that they cover. As author Jan Karon spoke through her character Father Tim, ”If there was anything more amazing and wonderful than almost anyone’s life story, he couldn’t think of what it was.” (p. 333, At Home in Mitford)

Explore the more than 300 oral history collections held by Wheaton Archives & Special Collections through our online archival database.