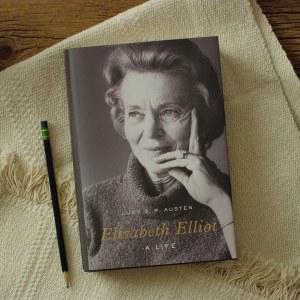

Wheaton Archives & Special Collections is pleased to announce that writer Lucy S. R. Austen will be our speaker for the annual Fall Archival Research Lecture! In anticipation of her upcoming visit, this month we feature a conversation with Lucy about her time researching for Elisabeth Elliot: A Life, her biography of missionary, speaker, and public evangelical Elisabeth Elliot, published by Crossway last June.

When and how were you first introduced to Archives & Special Collections?

I actually discovered the Archives & Special Collections through a Google search! In 2009, I was working on a mini-biography of missionary and author Elisabeth Elliot for a high-school English textbook featuring American Christian writers, and when I went looking for critical biographies of Elliot to learn more about her life, I was startled to discover that there were no full-length biographies of her in existence. Essentially the only published information about her life dealt with a small portion of the decade she spent in Ecuador as a young woman, working to reduce unwritten languages to writing for the purposes of Bible translation. In the process of digging around for any source material I could lay my hands on, I discovered the webpage for Elliot’s papers at Wheaton. I wasn’t able to visit the Archives at that time, but I relied on the biographical information and the list of “Exceptional Items” from the page for her papers, along with other sources, as I completed my project.

What kinds of research projects have led you to the Archives’ collections?

After completing that textbook I found that I kept on thinking about Elliot’s life. I was intrigued by what I’d been able to find in my research about her–she didn’t fit neatly into my preconceptions–and I wanted to know more about the woman who brought to life the most famous missionary story of the Twentieth Century and then went on to shape American evangelical theology in significant ways that continue to the present moment. In the summer of 2012, I woke up in the middle of the night thinking about different ways to outline the story of her life, and at that point I decided that I would start trying to write the book I wanted to read.

At first I worked primarily on locating sources and conducting interviews, knowing that time was limited for Elliot’s generation. I ended up conducting more than two dozen interviews, many of which raised additional questions. When Elliot herself died in the summer of 2015, I coordinated a trip to the Archives to coincide with her memorial service, which was held in Edman Chapel. I made a second trip in early 2020, which unbeknownst to me at the time was just before everything shut down because of the pandemic. Since many of Elliot’s papers were sealed for a period of 40 years from the date of the latest document in a given folder, I had intentionally left my visit as late as possible before my manuscript deadline, to let as many papers as possible become available.

What kinds of collections have you used most heavily and how were they applicable to your topic?

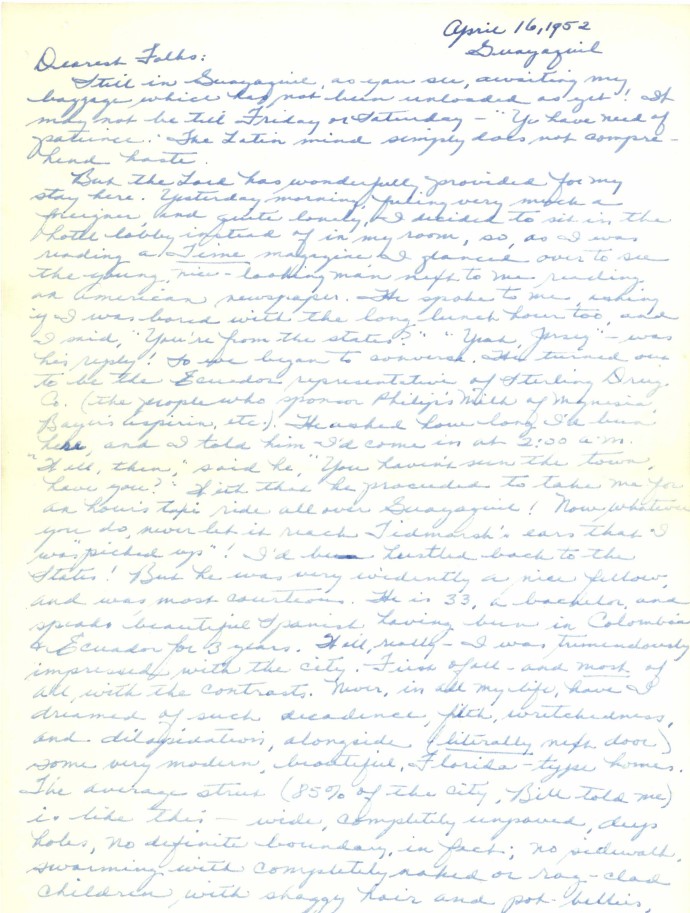

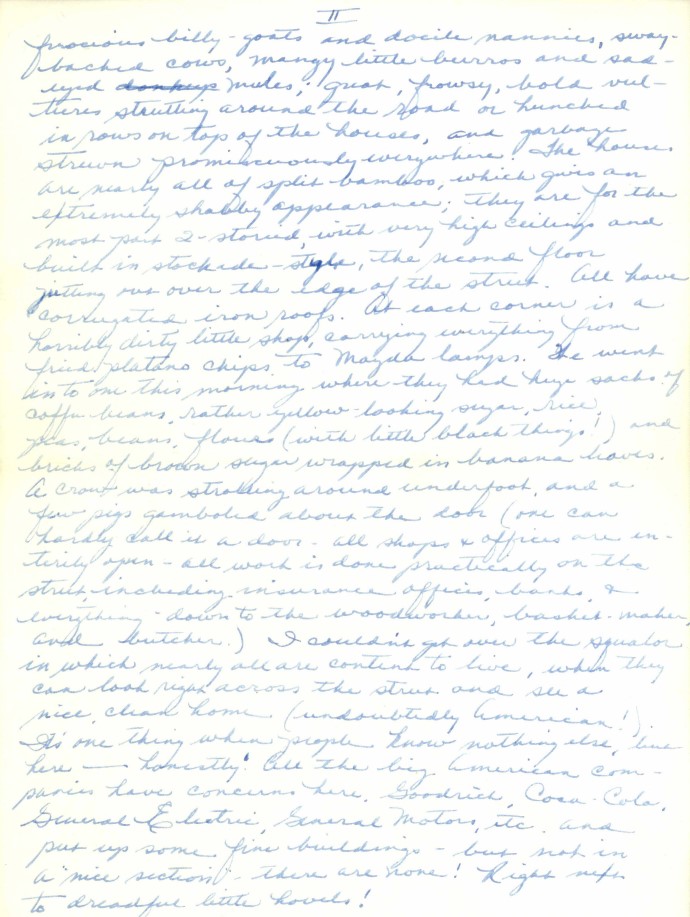

I spent the most time, of course, with Collection 278: Elisabeth Elliot Papers. It is an incredibly rich collection, a biographer’s dream. It holds decades of personal letters and business letters, letters Elliot wrote and letters others wrote to her, book manuscripts and recorded speeches, press clippings and scrapbooks and photo albums and slides, file folders full of form letters and statements on a range of topics from A to Z that Elliot used to answer her tsunami of fan mail, and on and on. I also spent a lot of time with a portion of Collection 670: Papers of Kathryn Rogers Deering. Deering was for many years the editor of the Elisabeth Elliot Newsletter, and her collection contains photographs of portions of Elliot’s journals, the only publicly accessible portions of those very important sources. The ability to compare the way Elliot wrote about events, first in public letters written to financial supporters, then in private letters written to family, and finally in her private journals, gives important insights into the inner life of a very private person and helps us understand the way she processed her thoughts and feelings and responded to those around her.

Perhaps more surprisingly, since Elliot went to the mission field under the auspices of the Plymouth Brethren, the papers I spent the next largest amount of time with were Collection 165: Evangelical Fellowship of Mission Agencies Records. I was very grateful to be granted access to these files, which enabled me to tease out the story of the previously obscure Missionary Martyrs Fund, the clearinghouse for the massive outpouring of donations after the deaths of Jim Elliot, Pete Fleming, Ed McCully, Nate Saint, and Roger Youderian. I also accessed several collections related to Elliot’s family, friends, and coworkers, including Special Collections 46: Luci Shaw Papers; Collection 192: Papers of Harold Lindsell; Collection 136: Ephemera of Missionary Aviation Fellowship; Collection 701: Papers of Olive Fleming Liefeld; Collection 684: Papers of Bert and Colleen Elliot; Collection 484: David M. Howard, Sr., Papers; and of course Collection 277: Ephemera of Jim Elliot. Some had quite a lot of pertinent information and some only a stray sentence or two, but they all contributed to a richer picture of Elisabeth Elliot’s life.

What can be intimidating about archival research?

The sheer quantity of material is intimidating. Collection 278 alone contains materials from eight decades! Much of the material I needed to examine was hand-written or typed on both sides of translucent paper (so that it was cheaper to mail internationally). Sometimes the typewritten letters were harder to read than the handwritten because the typist used such a worn-out typewriter ribbon. These documents took time and care to decipher. I took as many photographs as I possibly could so that I could examine materials carefully at home, which proved to be invaluable. I also worked with a few different research assistants who were on campus, to gain access to materials between visits.

The staff at the Archives and Special Collections really helped lessen the intimidation factor, and were very helpful in navigating the entire process. Katherine Graber, Bob Shuster, and Keith Call all answered questions by email and in person, suggested collections or documents that wouldn’t have occurred to me, helped me triage materials to make the most of my limited time on site, provided access to accessions that had not yet been processed, and even helped with some final details remotely during the pandemic shutdowns.

Do you have a favorite collection or one that has yielded unexpected treasures?

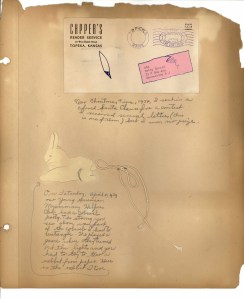

I’ve mentioned the EFMA records already, but additionally the 2019 accessions to the Elisabeth Elliot papers were particularly welcome. They contain a number of documents that shed light on what were otherwise blank spots in Elliot’s later years, particularly on aspects of her second and third marriages and on the development of her position as a prominent teacher on the roles of the sexes. And the scrapbooks are just delightful! The scrapbook from her childhood in particular, with its saved letter from L. M. Montgomery, early short stories, programs from plays, snapshots of friends from camp, etc., really brings the young Betty to life in a way that her later writing, looking back at herself from the vantage point of adulthood, just can’t capture, and gives fresh insights into her personality.

In your experience, what is the best part of archival research?

There can certainly be a sense of wonder or awe in getting to see and handle artifacts from moments in history that you’ve read so much about–the filing box containing Elliot’s Waorani language cards, for example, which were faithfully mailed from New Jersey by Elliot’s mother since 3×5 cards weren’t available in Ecuador, then painstakingly filled in by the fire in a thatch-roofed house in the jungle. But I think for me the best part of archival research is the detective work, chasing down research trails, not knowing exactly what’s there but discovering the story as you go along, sometimes finding answers you hoped were there but weren’t sure about, sometimes finding pointers to questions you didn’t even know to ask. It’s the best part of the job.

What project are you currently working on?

I’m about to start work on a biography of Elliot for middle grade readers. And I’m trying to clean up my research materials for donation to the Archives, particularly the original interviews, so that they’ll be available to future researchers. I hope we’re just at the beginning of scholarship on Elliot’s life and work.

Lucy S. R. Austen is a freelance writer who loves to curl up with a cup of tea and a good research trail. Her book Elisabeth Elliot: A Life, which is the first full-length single-volume biography of that remarkable woman, appeared in the summer of 2023. S. R. Austen’s work has also appeared at Christianity Today, the Gospel Coalition, the Oxford Centre for Life Writing, and more. You can connect with her on Twitter, Facebook, Substack, and through her website at lucysrausten.com.