March is Women’s History Month! In celebration, the Wheaton Archives & Special Collections spotlights the stories, voices, and legacies of women who blazed trails as medical workers, linguists, preachers, evangelists, educators, CEOs, and more found in our collections. Today, we highlight missionary Joy Ridderhof (1903-1984), founder and director of Gospel Recordings, whose pioneering work in portable sound recording captured thousands of indigenous languages in remote corners of the globe. Today, these Gospel Recordings represent the preservation of oral cultures around the world and contain high research value for historians, missiologists, linguists, and anthropologists studying these cultures.

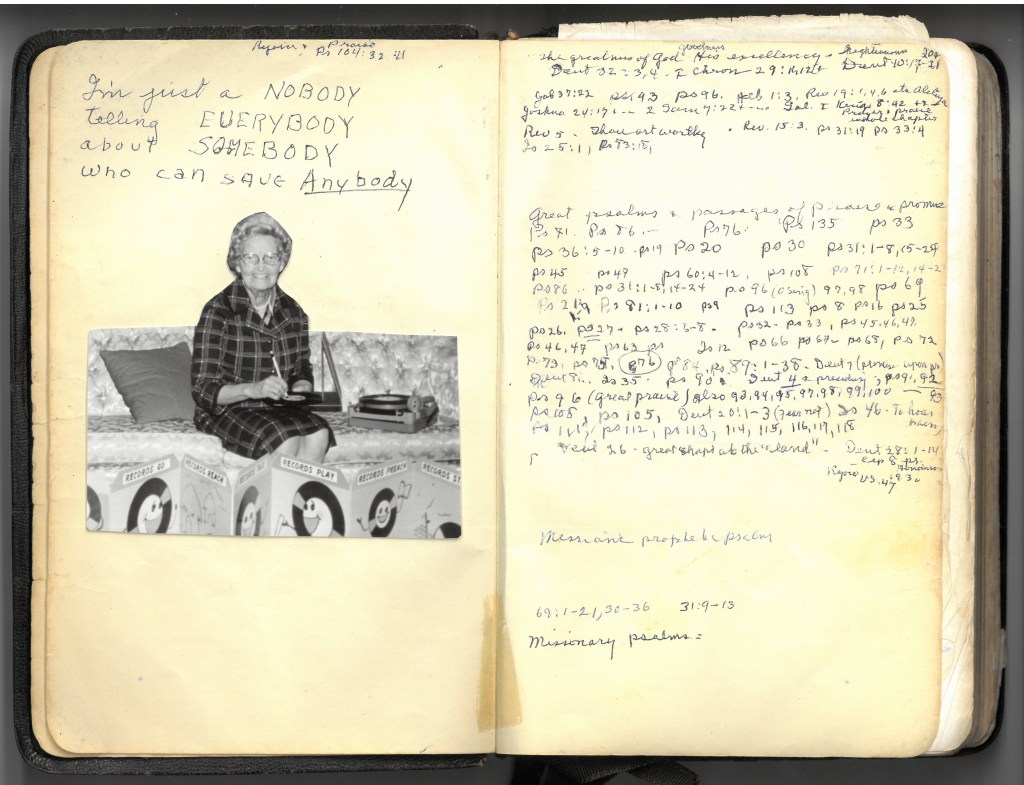

Joy Ridderhof’s story has been told in biographies like Phyllis Thompson’s Count It All Joy, and institutional histories of Gospel Recordings, like Faith by Hearing, but many of Ridderhof’s personal papers remain untouched in the archives’ holdings, and many of the documents and images featured here are located in unprocessed portions of the Gospel Recordings Records.

Born in 1903 to immigrant parents from the Netherlands and Sweden, Joy Fanny Ridderhof was less than a year old when her family moved from the frigid tundra of Minnesota to southern California, where the Ridderhof family home in Los Angeles would eventually become the headquarters and first recording studio of Gospel Recordings. The youngest of six children, Joy was a precocious, active, and absent-minded child. Raised by devout Christian parents, she attended a local Evangelical Free Church with her family, and later a Friends Church, where thirteen-year-old Joy had a conversion experience after hearing a sermon by a visiting woman evangelist.

Joy’s interest in missions developed early in childhood. The Ridderhof family played host to a steady stream of visiting missionaries whose stories of life and ministry on the field fired young Joy’s imagination. Her family, however, couldn’t envision their impetuous and high-spirited daughter as missionary. “Our Joy is much too fun-loving and impractical to be a missionary,” Mr. Ridderhof told a visiting Quaker missionary [“The Rejoicing Crisis,” p. 1]. Despite her failure to conform to the steady, pragmatic missionary candidate ideal, Joy continued to dream of foreign missions and set her heart on serving in Africa, waffling between either Africa Inland Mission or the Sudan Interior Mission as a sending agency.

Joy Ridderhof’s journey toward the mission field took an unexpected turn at the end her first year as a student at U.C.L.A. when she heard Robert. C. McQuilkin preach at a local conference. A notable Christian author and speaker, McQuilkin was known for his “Victorious Christian Life” message, in which he called hearers to live completely surrendered to God and strive for daily faith-filled victory over temptation. McQuilkin’s preaching transformed Joy’s understanding of the Christian life. Instead of completing her degree at U.C.L.A., she crossed the country to attend Columbia Bible College in South Carolina, a brand-new Christian school founded by McQuilkin.

After graduating in 1923, Joy remained on the East Coast for the next two years, serving at a Southern Presbyterian Church in Miami, Florida. But her call to missions work brought her back to Los Angeles to complete her studies for her teacher’s credentials at U.C.L.A. and prepare for field work in Africa. By the spring of 1930, effects of the Great Depression were widely felt by average Americans, but Joy was undeterred in her conviction that God was calling her to faith missions in Ethiopia or Sudan. Days before her graduation, however, a representative of the Friends Mission Board contacted Joy. Would she be interested in filling a missionary vacancy in Honduras? Faced with this request, Joy Ridderhof questioned her call to Africa for the first time and prayed for clarity. “But no special message was given me,” she later recalled, “just the general impact of the Great Commission.” Instead of insisting on the Sahara, Joy concluded “the time is short” and accepted the Friends Mission invitation, setting her sights on Central America [“The Rejoicing Crisis,” p. 3].

For the next six years, Joy Ridderhof experienced firsthand the travails of missionary service—both the mundane and the momentous. At the local level, the fledgling Friends Mission in the remote village of Marcala in the La Paz district faced opposition from Roman Catholic clergy, while the country of Honduras was afflicted by political upheaval and multiple revolutions. Travel was dangerous, the living conditions demanding, and medical care scarce. In 1936, Joy returned to Los Angeles on furlough, recovering from a debilitating case of malaria. Wracked by fever and weakness, Joy spent the next year in the attic bedroom of her childhood home, yearning to be back in Honduras. When she failed to recover her health quickly, the Friends Mission eventually dropped her support, and Joy Ridderhof was confronted by the reality that her plans to return to Marcala might be permanently stymied. Years later, Joy pointed to this moment of vocational crisis as the seedbed for what would become Gospel Recordings. “God could use me right there in my garret as well as on the mission field,” Joy concluded. “If I would wait, with rejoicing, faith, and expectation, God would work in some greater way to reach the unreached in Honduras” [“The Rejoicing Crisis,” p. 3].

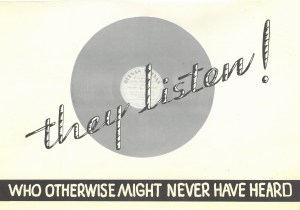

Unable to preach the gospel to Hondurans in person, Joy turned to another medium to transmit the simple gospel message—gramophone recordings. Recalling the Honduran love of recorded music and the centrality of gramophone players in village culture, Joy began taking guitar lessons and practiced singing in Spanish. With the support of fellow missionaries who had recording experience and equipment, Joy produced her first Gospel record on December 31, 1938, a three-and-a-half-minute master recording titled Buenas Neuvas composed of hymns and Bible verses in Spanish. From her attic bedroom, Joy shipped copies of Buenas Neuvas to missionaries all over Honduras and was soon flooded with requests for more recordings from Christian workers all over Latin America.

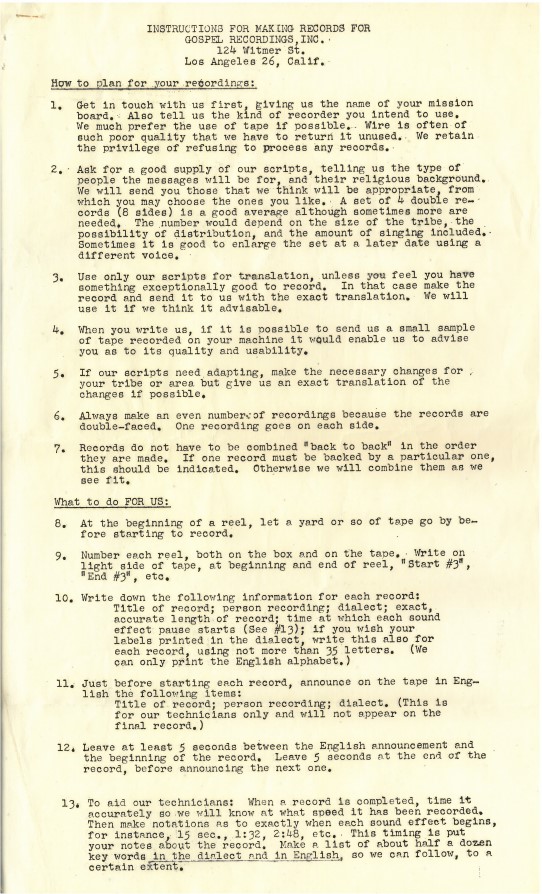

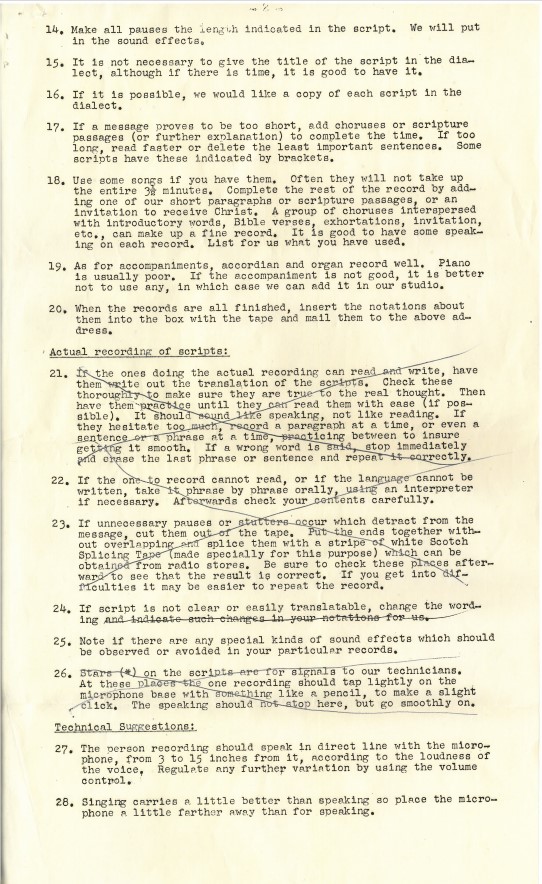

Despite the immense demand, Joy quickly realized the limitations of her first recording. While fluent after six years in Honduras, she worried that listeners might learn the gospel message and hymns in America-accented Spanish. Soon Joy was recruiting native Spanish-speaking preachers and musicians from the greater Los Angeles area to record her short, punchy scripts. To cope with the flood of requests, Joy recruited a college friend, Ann Sherwood, to join the ministry, converted the garden shed into a proper recording studio, and incorporated Spanish Recordings in 1941.

By the early years of the 1940s, Spanish Recordings’ little black discs had found their way into Puerto Rico, Mexico, Columbia, Peru, Venezuela, Chile, and even to Spanish-speaking regions of the Philippines. Together, Joy and Ann had produced dozens of master recordings and branched out into other languages. When missionaries to the Navajo Indians in Arizona asked for records in indigenous Native American languages, Joy found native Navajo speakers to translate and record the scripts.

A pivotal shift occurred in 1944, transforming the Los Angeles-based ministry into a global recording enterprise and taking Joy Ridderhof back to the mission field. While each week brought new requests from missionaries and Christian workers around the world, even the diverse population of Los Angeles could not provide native speakers for all the languages requested.

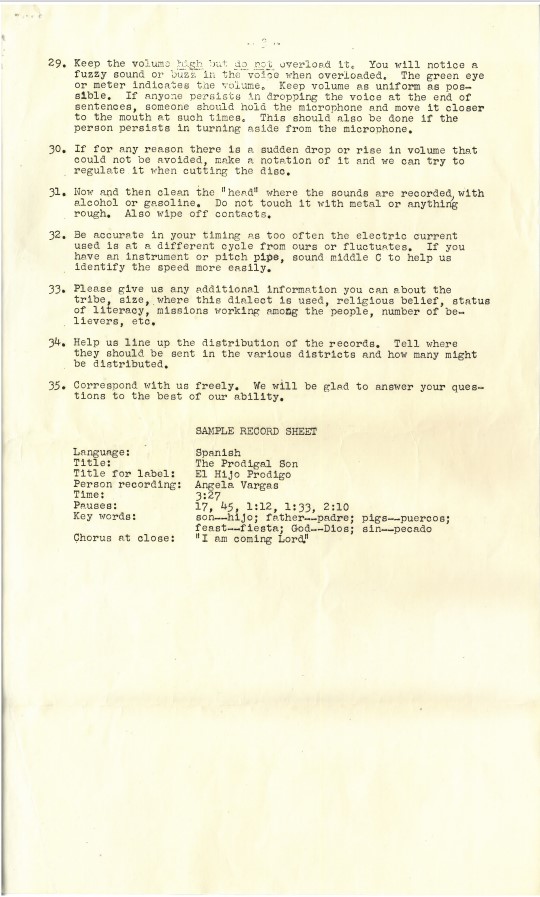

When missionaries with Wycliffe Bible Translators in Mexico requested gospel recordings in the Mazahua language, Joy and Ann packed the studio equipment and left for the southern border in a donated station wagon. For the next 10 months, the duo recorded gospel messages in thirty-five languages and dialects across Mexico and Central America. From 1944 onward, Joy and her ministry team adopted this new model. No longer would native speakers be required to visit the studio in the Ridderhof home to produce gospel recordings. Instead, the studio traveled to native speakers.

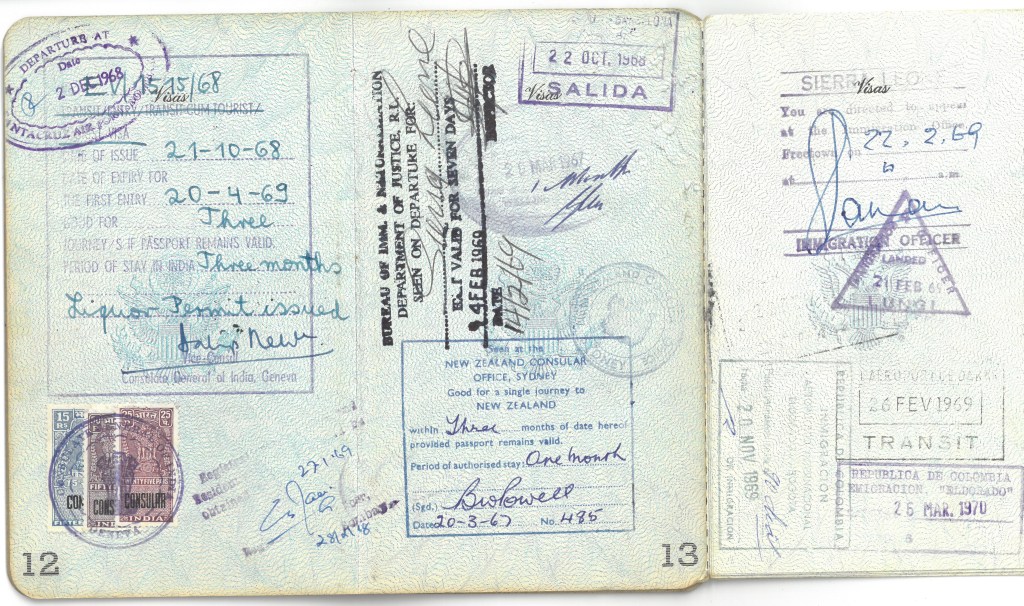

Over the next decade, Joy and Ann made trips to Alaska to capture over a dozen indigenous languages, to the Philippines, where they recorded over 90 different languages and dialects, and on to Australia, Indonesia, New Guinea, and eventually Africa. By 1955, over a million Gospel Recording records had been shipped to over 100 countries around the world, and a second Gospel Recordings branch was founded in London.

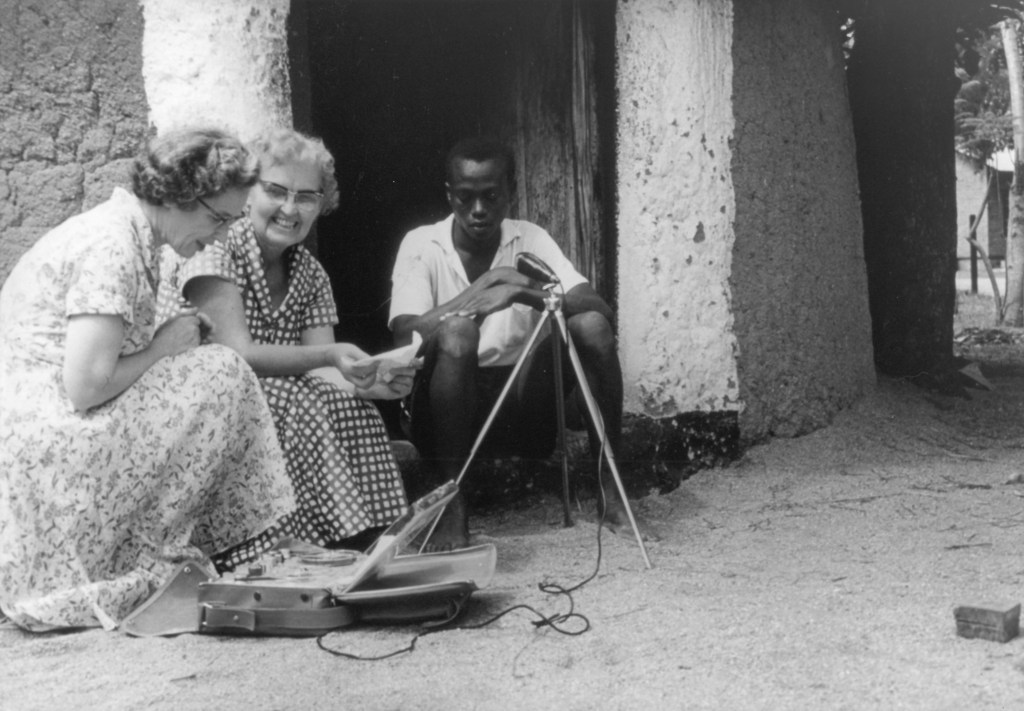

Joy Ridderhof and Gospel Recordings pioneered not only a ministry model but also popularized new playback equipment. Gramophone players of the era were heavy, unwieldy, and highly susceptible to deterioration in the humid climates around the world. Over the years, Gospel Recordings has relied on simple hand-cranked audio players without batteries, including Cardtalk (featured at the beginning of this clip from the PBS documentary The Tailenders) and later cassette tape players.

Joy Ridderhof died in 1984 at the age of 81 and is buried in Valhalla Memorial Park in Los Angeles County. Her legacy continues in the work of Global Recordings Network (formerly Gospel Recordings), and today thousands of indigenous languages have been captured and used to spread the simple gospel message around the world. The Gospel Recording Records held in the Wheaton Archives & Special Collections contain hundreds of these recordings, from Henghua (China) to Makonde (Tanzania), to Tondano (Indonesia). A full list of the thousands of sound recordings is found here.

Pingback: Our God of Abundant Supply | From the Inside Out