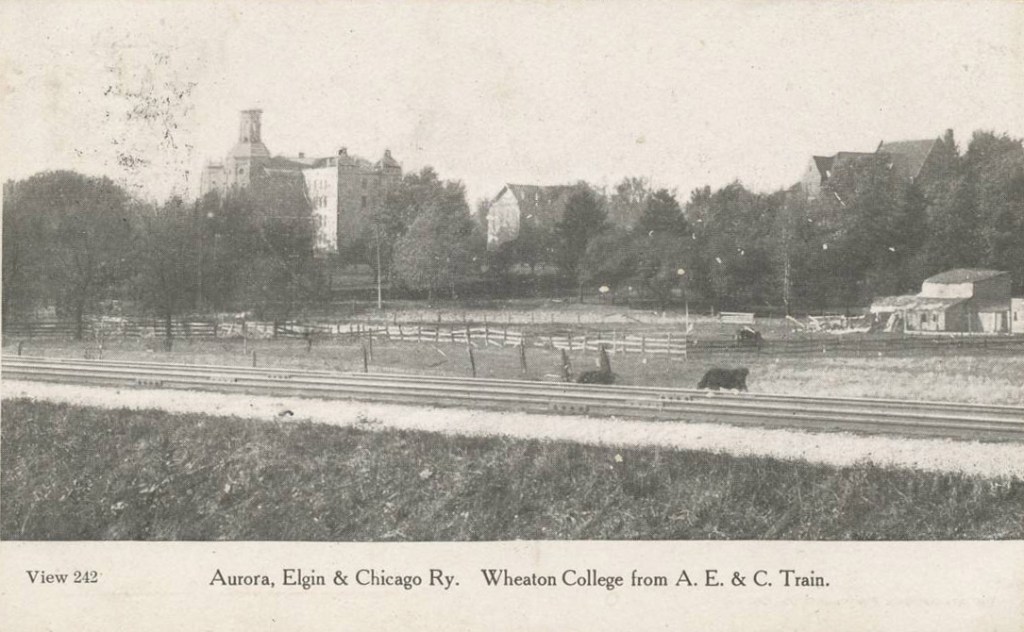

For nearly sixty years the primary means of transportation for Wheaton College staff, students or anybody traveling from the Fox River Valley into the concrete canyons of the Windy City was the Chicago, Aurora and Elgin railway. Established in 1902, the locomotive, called “The Roarin’ Elgin,” conveyed passengers and freight between Chicago, Geneva, Batavia, Aurora, Elgin and St. Charles. Because evening trains headed westward from Chicago into the setting sun, it was also romantically (but unofficially) nicknamed the “Sunset Lines.”

As automobiles increasingly dominated American life, interest in commuter trains quickly diminished. Consequently the CA&E abruptly ceased operation for passengers in 1957, riding into the sunset for the last time. Two years later freight transport ended, and on July 6, 1961, the Illinois Commerce Commission authorized the CA&E to permanently abandon all transportation service and remove, sell or dispose of property or trackage not used by other railroads. Since then long stretches of the old CA&E tracks in Kane County have been paved, and is now called the Illinois Prairie Path, daily used by joggers, cyclists and walkers.

Using personal memoirs and oral history interviews held in our collections, Archives & Special Collections takes a journey through the history of the Aurora-Elgin railroad, exploring the intertwined narratives of Wheaton College and the local history of DuPage County.

Long-time Wheaton coach, Edward A. Coray, recalls in his memoir, The Wheaton I Remember (1974), his first student job at the Wheaton station, a major switching junction for the railroad and home base for its paint and carpentry shops,

I started at an eating joint in the Chicago, Aurora and Elgin railroad station. After learning the trade there, I graduated to what might loosely be termed a dining room in a fifth or sixth class hotel at the southwest corner of Crescent and Hale streets, just south of the railroad tracks.

Coray wryly adds,

Riding the old Aurora, Chicago and Elgin train, usually called “the Roaring Elgin,” was an experience in itself. It was run by an electrified third rail and bounced around like a ship in a storm. It went defunct some years ago. In fact, it was defunct a few years before that but as someone said, “It kept running from force of habit.”

Another Wheaton student with a job on the AE&C Train was Russell Shed, who attended both Wheaton Academy and Wheaton College in the early 1940s. He recounted his experience in 1982 oral history interview with Galen Wilson:

SHEDD: Well, by skipping the grades…that one grade in…in high school. So I started Wheaton at sixteen and finishing by studying in summer school. By working on the railroad, there was very little do except to study on this…you know, Chica…Chicago, Aurora and Elgin. So that’s the reason.

WILSON: You were a…

SHEDD: Crossing watchman.

WILSON: What does a crossing watchman do?

SHEDD: Well, he runs those gates that they used to…were not automatic at that time. They were run by people, but…

WILSON: All the little ding-ding-ding gates?

SHEDD: Yes, on…right down here in Wheaton and also all the way down into to Maywood. We worked as far east as First Avenue, Maywood, and that was the end. Now everything is elevated, I guess, so….

WILSON: Now…and every one of those gates required somebody to stand there and…?

SHEDD: Yes. Well, you had a little tower at that time. They weren’t…they worked by air pressure, and…so you’d work these levers and drop these gates. You’d get an automatic ring which let you know the train was coming from whichever direction and whichever track, and so you had to be very cautious that [laughs]…make sure those gates were down. It was…it was a good experience, but sometimes hair-raising.

CN 201, T1. Russell Shedd

Archives & Special Collections also holds an 1977 interview with long-time Wheaton and Glen Ellyn resident, George Goodrich, who grew up in a house on Pennsylvania Ave in the 1920s. Along with his memories of his father’s work as a teamster and life in the Western suburbs during the Depression, he recounts the distinctly-Chicago saga of the Roarin’ Elgin:

INTERVIEWER: What about the Roarin’ Elgin? That was built in 1901 or something like that?

GOODRICH: Yes, she [his mother] remembers when the first cars run, they all went to town to see the train run without an engine. And then she saw the last one.

INTERVIEWER: What do you remember about it? Did you ride it often?

GOODRICH: Well, it was…first it was reasonable and cheap transportation, and it ran every twenty minutes. So, you never worried about a timetable. You went down there, and you’d catch…first there’d be the limited and then the local. The limited would hit the main stations and the local would stop at every station. So, if anybody’d miss the limited, they could take the local. And the limited was usually three or four cards and the local was one or two cars. And they had a pole in those Roarin’ Elgin cars that in case they got stalled on a crossing the conductor would go up and touch the next third rail and pull it across.

INTERVIEWER: Oh really, I see.

GOODRICH: There are some of those Roarin’ Elgin cars in the South Elgin…in that railroad complex in South Elgin.

INTERVIEWER: Did that run in competition with the Northwestern?

GOODRICH: Oh, yes.

INTERVIEWER: So, they were both running commuter service the whole time?

GOODRICH: Yes

INTERVIEWER: And they both kept in business for…

GOODRICH: Well [Mayor] Daley killed it.

INTERVIEWER: How? What did he do?

GOODRICH: Well, when they went to put the tollway in, Daley did not give them permission to go back to Wells Street. The government had guaranteed the railroads they could go back to Wells. But in the meantime, the administration changed, and Daley wouldn’t stand for them coming back in over the CTA tracks to Wells Street, because it ran into Well Street.

INTERVIEWER: Okay, so it really got killed in Chicago because you couldn’t go far enough?

GOODRICH: That’s right. Might have helped that the Mayor of Chicago [knew] the guy that was replacing the Northwestern railroad. So that triggers the…the elevated now runs almost out to Oak Park and the Northwestern right-of-way. That was the deal.

INTERVIEWER: Yeah, I see. I didn’t realize that. I thought it was just…it mostly died because it went bankrupt because it couldn’t compete anymore with the Northwestern.

GOODRICH: Oh, the presidents and vice-presidents got too much money. They got something like two-three hundred thousand a year and a little railroad like that did two hundred thousand. They couldn’t pay it. The presidents of the Roarin’ Elgin helped kill it too. The Wyatts chose Aurora, Elgin, and Chicago because Aurora was named by the Aurora Lights because it was the first place that had electricity around here.

INTERVIEWER: Aurora was?

GOODRICH: They had it off the river. So, when the electricity was made in Aurora, the Roarin’ Elgin started from Aurora to Chicago and then up to Elgin. They used the power from the river.

INTERVIEWER: Did they build the tracks from Aurora to Elgin at the same time?

GOODRICH: Well, no, they went to West Chicago too. And they went out farther than West Chicago and had one line along the Fox River, from Elgin to Aurora. I never knew what really happened to it. I believe they got as far as Sycamore. I remember when I was small, we went out to Dundee on the Roarin’ Elgin. How it went there, I don’t know. I was very small. I went with my mother for parts for a pump.

INTERVIEWER: I thought it was just a “Y,” you know. That one section went to Aurora and one section went to Elgin.

GOODRICH: Well, it was also killed by Morgan. Well, this guy. What was his named that owned the Roarin’ Elgin….I think it was later. Well, anyway they were putting electricity in out here and J. P. Morgan wanted certain parts of Indiana and a fella started putting the light lines into Indiana. They’d run ‘em on top of the poles and hang one lightbulb and that would their territory… in the farmer’s house. They were so interested in getting territory for their light circuits. And J. P. Morgan, he bought up the Roarin’ Elgin mortgage and that’s how he helped kill it too.

INTERVIEWER: Oh, really?

GOODRICH: Big money. The guy’s name was…wasn’t Etzel….an odd name. I’d have to look that up. That’s the way the Roarin’ Elgin died. They had the Western United Gas and Electric Company, that’s what they were running.

INTERVIEWER: They owned it? It was a subsidiary?

GOODRICH: Of the Roarin’ Elgin, yeah. That’s when J. P. Morgan took it over and they went in and changed to Edison.

George Goodrich Interview, College Archives Tape 77-14

A significant part of everyday life for the residents of Wheaton and DuPage county, the Chicago-Aurora-Elgin railroad also played an important role in connecting Wheaton College to the wider Chicago community and suburbs. Former Wheaton students, Raymond Saxe and Vincent Crossett, shed light on their experience commuting on the Roarin’ Elgin in these excerpts from two oral history interviews:

SHUSTER: What years were you at Wheaton?

SAXE: In 1940 to 1944.

SHUSTER: And why did you chose to go to Wheaton?

SAXE: Well to tell you quite frankly it was proximity to our home. We lived in Oak Park, Illinois. And so I could take the…what we used to call the Roaring Elgin from Oak Park to Wheaton. And also my father attended the Academy many years before.

SHUSTER: Did you take the train back and forth or did you drive?

SAXE: Yes I took the train. What we call the Roaring Elgin. It’s not…not in use anymore I don’t think.

SHUSTER: Was that the train or was that the trolley car?

SAXE: No, it was like an elevated train. It went from Aurora and Elgin into the city of Chicago. And I think those tracks have been pulled up completely. And I don’t think the service is available anymore.

SHUSTER: No, perhaps the current train follows the same route, I imagine.

SAXE: Well, I don’t think so because these trains from Aurora and Elgin and passed through Wheaton went on through Chicago through…onto the elevated train. And the elevated train I think picked up somewhere around Broadway or Westchester. And you could get the local train there. But this Roaring Elgin was given priority. And it had different kinds of cars than the cars that were used in the elevated trains in Chicago.

SHUSTER: How many students like yourself were commuting from Chicago, do you know?

SAXE: Oh I guess about fifteen or twenty. I’d meet them on the seven o’clock train or the 7:20 train everyday.

SHUSTER: And how far a walk was it from where you got off the train to the college?

SAXE: Oh it was about…I would say about fifteen minutes. I often had to run if I took the 7:20 train and had an eight o’clock class. I had to run [laughs].

Raymond Saxe, CN74, Tape 70

ERICKSEN: Did you ever get into the…into Chicago while you were here?

CROSSETT: Occasionally. Occasionally we all went into Chicago for [clears throat]… sometimes for events we went in on our own. We…we’d go into the Art Museum…the Field Museum, I mean, and the…the…the [Adler] Planetarium. We’d go occasionally, not…not too often. Sometimes we’d just go shopping.

ERICKSEN: Take the train in?

CROSSETT: Yeah. The inter-urban. Not like these…these…what do you call it? Not the three-wheeler, but the third track. They got their electricity from the third track down here. That’s all closed up.

ERICKSEN: Like the streetcars?

CROSSETT: Chicago, Aurora, and Elgin they called it. Chicago, Aurora, and Elgin. And they’d come out here, go to…go to Aurora, go to…go to Elgin and [unclear]. That was…just get on that train. You could get the other one, too, if you wanted to go straight through, but…but we usually went [unclear]. I think it was cheaper, and we liked the place where they stopped in Chicago.

Vincent Crossett, CN 288, Tape 1

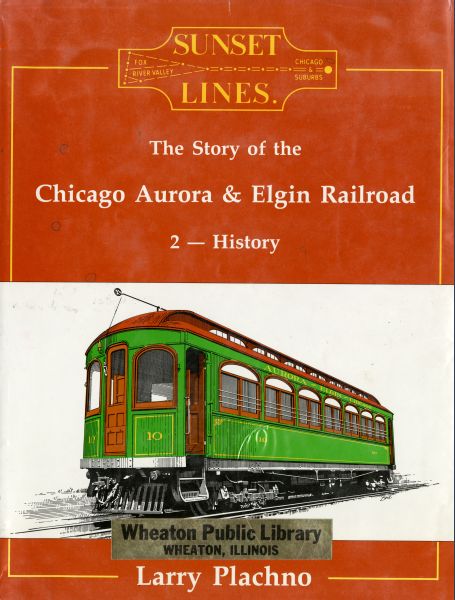

The CA&E switching yard, equipment shops and dispatcher’s office, long since demolished, is the location of ReNew Wheaton Center, a complex of high rise rental units. Larry Plachno in The Story of the Chicago, Aurora and Elgin (1989) relates the heritage of this great, not-quite-forgotten Chicago railway.

Several pieces of CA&E passenger equipment have been preserved by operating museums. Although the scenery may be different, you can still ride on CA&E cars at several of those trolley museums and relive the good old days when the Chicago, Aurora and Elgin connected Chicago and the Fox River communities with fast, frequent electric interurban service.

Retired CA&E cars and other paraphernalia from its heydey are currently exhibited at the Fox River Trolley Museum in South Elgin, Illinois. Another limited exhibit on the history of the Elgin-Aurora line and its relationship to the Wheaton community will open on June 10th at the DuPage Historical Society Museum.

Explore more oral history interviews recounting local history with Wheaton and DuPage county residents through the College Archives Oral Histories Collection.